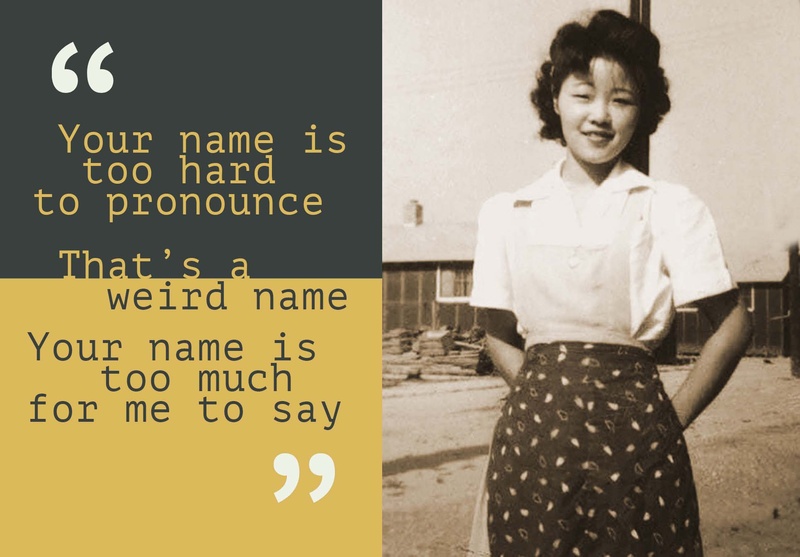

My mother’s name was Margaret. But actually it wasn’t. Her kindergarten teacher gave her this name, after saying my mom’s actual name, Tsutako, was too hard to pronounce. “That’s just how it was,” my mother said. I never asked her how she felt about her American name, given to her by a hakujin woman who thought it was within her right to rename a five-year-old without consent from her or her family.

At the first volunteer meeting at my daughters’ new school I eagerly raised my hand to help out at a bake sale. When I said my name, Marsha Takeda-Morrison, the PTA president said, “Oh, that’s too much. Let’s just use Morrison.” I guess that’s just how it was twenty-five years ago? I wasn’t sure then how I felt about this hakujin woman who couldn’t be bothered with the part of my name that bore my Japanese roots but I decided I couldn’t be bothered to sell cupcakes at her bake sale, either.

A few years ago, I posted an article about a Vietnamese college student who was being asked by her professor to “Anglicize” her name because he thought her given name “sounds like an insult in English.” A hakujin friend commented on my post, saying she agreed with the professor because the student’s name was “weird.” When I, along with many others, pushed back she responded by saying she felt “attacked” and then blocked me. That’s how it was. I never spoke to her again, so I never got to ask her how she would feel if someone called her name “weird” and asked her to change it.

My dad didn’t give me or my four siblings Japanese middle names, as most Japanese Americans did back then, because he didn’t want to call attention to our race and give the bigots a reason to target us. That’s just how it was back then, after the trauma of the camps had left them scarred and shaken. We had no say in the matter but my sister and I—with my middle name, Jean, and hers, Sue—weren’t always happy with our monikers that made it sound like we were in a country band. But we understood the reason.

As a child, I didn’t realize that a lot of the American names my relatives and friends’ parents had were not their given names. George, Grace, Tom, Helen. Even my dad went by James more often than his given name, Hiroshi. Did they Americanize their own names to avoid discrimination? Were they given to them by a PTA president who thought their names were just too much, or an indifferent schoolteacher who didn’t want to even try letting the delicate Japanese syllables roll off of her coarse tongue? Maybe that’s just how it was back then. I wonder how they felt about their names.

Is a name just a name? For some of us, it’s much more than that. They’re a connection to our heritage, our families, our ancestors. By refusing to call us by our names, you’re telling us we’re not valued and that we need to change who we are for your convenience. It often feels like people want to erase our names, in much the same way they’ve tried to erase us.

When my oldest daughter was born, I gave her the middle name Tomiye, after my grandmother. My younger daughter’s first name is Kiyomi. I wonder if, in this world that is becoming less tolerant and more xenophobic, my daughters’ names may be a hindrance in the future or make them more frequent targets of racism. Will someone ever try to strip them of their names that speak of their Japanese ancestry? Is that just how it’ll be, in our country that’s becoming increasingly governed by hate?

I know exactly how I feel about it.

© 2024 Marsha Takeda-Morrison

Nima-kai Favorites

Each article submitted to this Nikkei Chronicles special series was eligible for selection as the community favorite. Thank you to everyone who voted!