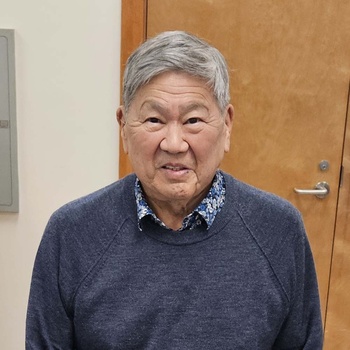

“Art Miki’s sansei reticence, his slapshot, unassuming diligence, devotion to the JC community, sense of humour, background as an educator, love of soba noodles, Winnipeg address, and his ability to draw in and count on the talents of others, made him the perfect leader for the JC Redress Movement.”

— Bryce Kanbara, member of the NAJC Redress Strategy Committee

Way back in the 1980s, the Japanese Canadian community was connected to the past in intimate ways that may be unimaginable today, especially for millennials.

As a community then, we were in the throes of the redress campaign—at a time when JC politics, identity and community first came on to my radar and there were still Issei and older Nisei around, whose stories I could mine. I wonder how younger Nikkei now even begin to get a grasp on their Japanese Canadian identity.

While puttering about in the late eighties, I had no interest in learning about the internment or what the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) was up to. What my family and community had lost during the internment had little impact on who I was in my twenties: that my own democratic government had stolen the Ibuki family farm and property in Strawberry Hill, BC and put my family into prison camps really did not compute.

So, just 25 years or so after the end of WWII, it was a few Nisei and older Sansei, many of whom were the first generation of Japanese Canadians (JCs) who had the opportunity to become lawyers, teachers, doctors, professors, who were inspired to get together to take on the federal government in what became the redress movement.

* * * * *

In the late 1970s, the NAJC held its first national meeting after about fifteen years of post-War dormancy. The purpose was to revitalize the network of chapters across the country, and to coordinate plans to celebrate the JC Centennial year, 1977. Most of the attendees had never met one another. Art Miki from Winnipeg was one of the representatives. The eventful years following that galvanizing meeting saw a remarkable coalescence of JC communities, and a series of actions that stirred feelings of pride, communality, as well as the courage to confront the injustices of WWII.

When the National Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association was renamed National Association of Japanese Canadians in 1984, it was a politically inexperienced group of JCs that audaciously took up the fight for redress. The NAJC, with Art Miki at the helm, was focused on redress that included individual compensation. Toronto’s George Imai and Jack Oki’s Canadian National Redress Committee had an agenda that focused on symbolic reparation.

With the makings of a Netflix docudrama that somebody should really take on, the series would begin with Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, continue to develop around how Art became a teacher in 1962 then a modest Manitoban public school principal who walked from school halls into the halls of Parliament without breaking stride.

His JC activism began in 1977 with the events surrounding the JC Centennial that marked Manzo Nakano’s arrival in Victoria, BC. At that point it was about 25 years after the end of WWII, in the aftermath of the Bird Commission (1947-1950). Important books like Ken Adachi’s The Enemy That Never Was (1976), Ann Gomer Sunahara’s Politics of Racism (1981) and Toyo Takata’s Nikkei Legacy: The Story of Japanese Canadians from Settlement to Today (1983) were being published, adding JC voices to challenge the internment narrative that had been told until then.

In Toronto, George Imai and Jack Oki formed the Canadian National Redress Committee. They had been meeting with the federal government as early as 1983 to arrive at some sort of symbolic redress for “the national community.” This was following on the heels of the 1982 Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in the United States, which recommended $20,000 compensation to Japanese American internment survivors.

The experience of JCs whose personal property was lost was vastly different from that of Japanese Americans (JAs) who did not lose personal property. JAs were able to move back to the West Coast in 1944 versus 1949 in BC. JAs were not deported to Japan at the end of the war, but 4000 JCs were.

Through the redress negotiation process there was a quick succession of federal ministers of multiculturalism who were responsible for the portfolio: Jack Murta, Otto Jelinek, David Crombie and Gerry Weiner. In addition, Art Miki recognized the importance of opposition party voices from the New Democratic Party and the Liberals. It wasn’t until Weiner arrived on the scene in 1988 that the government softened its aggressive top-down stance of negotiating with the NAJC.

Behind The Scenes Revelations

Put yourself in the shoes of JC war veteran Harold Hirose from Winnipeg, who served as a Japanese-language interpreter in the 34th Indian Infantry Division that was part of the invasion force in Bombay (now Mumbai). Until close to the end of WWII, JCs were not allowed to enlist. They were only allowed to do so because the British needed Japanese-English translators.

So, how would you feel then if you were handed a cheque for $36 for the five-acre “confiscated” family farm in Surrey, BC, after all was said and done?

“What irked Harold most was that the government deducted a fee for looking after the property, a fee for the sale of the property and a charge for internment travel and food costs,” writes Art.

Hirose, a member of the NAJC’s Executive Committee, had his own run-ins with politicians. At one meeting with multiculturalism minister Otto Jelinek, an immigrant from the Czech Republic who attempted to empathize with the JCs as “a fellow immigrant,” Hirose responded with righteous indignation, saying: “You don’t understand our situation: you see, we aren’t immigrants. Most of us were born in Canada.”

Another revelation came during 1987 negotiations when, Art points out, “it would have been so easy to succumb to the government’s offer of a $12 community fund…. especially when David Crombie had emphasized that it was the final ‘take it or leave it’ offer.” When asked if he ever considered giving up during that four and a half year struggle, Art said: “I always maintained a solemn belief that we would somehow succeed. Regardless of the outcome, I believed that Canadians were benefactors, because through the public discourse, they gained a clearer understanding of the history and experiences of Japanese Canadians.”

Calculating the Cost of Compensation

An unexpected ally was Price Waterhouse president Phil Barter, whose father had been president of the money management company during WWII. Recalling that his father was upset at how JCs were treated and regretted that he didn’t do anything about it, Phil decided to honour his father’s memory by paying the upfront costs for the study to examine the losses, including loss of property, income, life insurance policies, pensions, and community facilities, as well as disruption of education. Able to raise only $40,000 of the total $150,000 cost for the study, the NAJC promised to pay the remainder if there was settlement.

The Price Waterhouse report, “Economic Losses of Japanese Canadians After 1941” (1986), calculated that at least $443 million was lost during the internment, based on $333 million in lost income and $110 in lost property (1986 dollars). This was a far cry from the “billions of dollars” that Jelinek had predicted. The findings of the report proved to be a turning point.

While it was clear that many politicians held openly racist views of JCs, we rarely get evidence of this in such a stark way as this. It was out of the blue that Art received a phone call from G. Murchison, whose father, Gordon Murchison, was director of the Veterans Land Act as well as of the Soldier Settlement Board during WWII.

He was “very closely involved in the valuation and ultimate disposal of lands” that were seized from JCs by the Canadian government. In a copy of a handwritten diary entry that he shared with Art, Gordon Murchison wrote that some 2,500 fishing boats were seized, as was industrial, commercial and residential property “worth many millions of dollars,” and no less than 1,100 small specialized farms in the Fraser Valley and Gulf Islands.

“The Hon. Ian Mackenzie, minister of veteran’s affairs, represented Vancouver South in Parliament and was insistent that the Japanese people would never return to the coastal areas as long as he could prevent it… Mackenzie held strong views that these Japanese lands should be taken over by the government and held for the re-establishment of Canadian veterans of World War II.”

Victory… at Long Last

Why had there been so many delays in the negotiation process prior to August 1988? Art writes that opposition came from the Prime Minister’s Office itself as well as Minister of Veteran Affairs, George Hees, a “zealous adversary” to making any amends to Japanese Canadians, resigned from Cabinet in April 1988. Lucien Bouchard, an advocate of redress, joined the Cabinet around this time.

In addition, the need to resolve conflicts of opinion within the JC community, and the importance of educating JCs themselves as well as Canadians in general slowed down the process. Jack Oki and George Imai were still throwing up roadblocks like presenting Toronto City Council a false list of organizations that opposed the NAJC when it awarded a grant to help defer the cost of the Price Waterhouse report.

South of the border, the US Civil Liberties Act was signed on Aug 19, 1988, giving Japanese Americans $20,000 compensation. This put more pressure on the Canadian government to get a deal signed.

So, in the final days leading to the signing of the agreement, Gerry Weiner, minister of multiculturalism, and Bouchard, putting pressure on the redress naysayers arrived at a final agreement on August 25th, 1988 that gave survivors individual compensation of $20,000, plus a symbolic $1000 above the US amount in recognition that the JC experience was “more severe” than the Japanese American one.

“As we (Prime Minister Mulroney) walked downstairs to the room in which the official signing of the agreement would be taking place, I said to him, ‘It’s taken a long time, but it was worth waiting for.’ His reply was, ‘Well, it’s taken this long for me to convince some of my colleagues that it was the right thing to do.”

Gaman, through the eyes of the JC who led the fight, gives readers a remarkable front row seat on the roller coaster ride that was the redress movement.

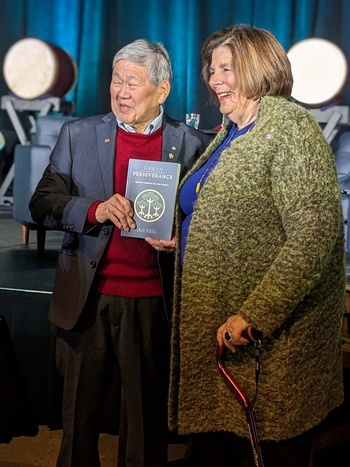

GAMAN: PERSEVERANCE—Japanese Canadians’ Journey to Justice

By Art Miki

(TALONBOOKS, 2023, 369 pages, $29.95 Canada/USA, paperback)

© 2024 Norm Ibuki