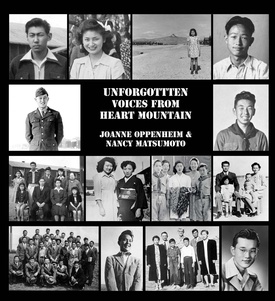

The book Unforgotten Voices from Heart Mountain by Joanne Oppenheim and Nancy Matsumoto captures the emotions and everyday life during World War II at the Wyoming concentration camp. Presented in a reader’s theater format, the book uses primary-source materials from both inside and outside the camp to illuminate the lived experiences at Heart Mountain.

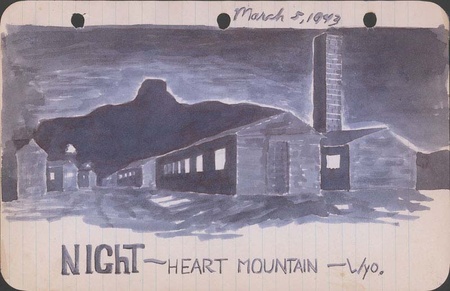

Voices features first-person oral histories from both imprisoned Japanese Americans and the nearby townspeople. The book also includes official documents and letters from camp administrators and newspaper articles or editorials that reflect the racism of the time. In addition, the many photos, diaries, drawings, and letters in the book portray the humor and pathos of life in Heart Mountain.

Unlikely Collaborators

On the surface, award-winning writers Joanne Oppenheim and Nancy Matsumoto appear to be unlikely collaborators.

Matsumoto is a freelance writer and editor who writes extensively about food and wine. She co-authored the 2023 James Beard award-winning Exploring the World of Japanese Craft Sake and wrote Displaced: Manzanar 1942-1945: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans. By contrast, Oppenheim is best known as a childrens’ book author of titles including Knish War on Rivington Street and Have You Seen Birds? She also reviews childrens’ products for her Oppenheim Toy Portfolio awards.

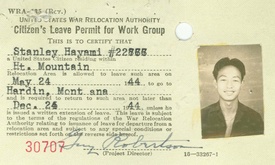

Oppenheim became interested in the incarceration while searching for a Japanese American classmate prior to a 50th high school reunion. This led her to the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in Los Angeles, where she stumbled upon the concentration camp stories that she would later use in her books Dear Miss Breed and Stanley Hayami: Nisei Son.

Oppenheim said, “What had happened to the Nikkei certainly resonated with my own Jewish family’s history of the death camps of Eastern Europe.”

Meanwhile, Matsumoto was trying to learn more about her family’s concentration camp experience. All four of her grandparents, her parents, and their siblings had been imprisoned. Her father’s family had been at Manzanar and Tule Lake and her mother’s at Heart Mountain.

In the book, Matsumoto said, “Like most Sansei, or third-generation Japanese Americans, I didn’t know much about this chapter of my family’s life until I was probably in high school. Even then, I had only a hazy notion of what had happened to them. No one talked about it, there was too much repressed shame and anger, I later realized.”

Chance Meeting and Friendship

By 2004 and 2005, Oppenheim was collecting first-hand accounts from people imprisoned at Heart Mountain. She traveled to Wyoming, Los Angeles, and even a Heart Mountain reunion in Las Vegas to interview people. However, she felt something was missing. So, the manuscript remained in a drawer for over a decade.

In 2008, Matsumoto attended a lecture by Oppenheim on her Stanley Hayami book. The two later became friends. Oppenheim eventually asked Matsumoto, who she calls “Editor Nancy,” to whittle down the Voices manuscript to a reasonable length.

As a descendant of the incarceration, Matsumoto was “the through line” that could tie together the Heart Mountain stories, according to Oppenheim.

Local Wyoming Opposition

Voices tells the story of Heart Mountain in chronological order, starting from the bombing of Pearl Harbor up until the end of WWII when people had to leave the camp.

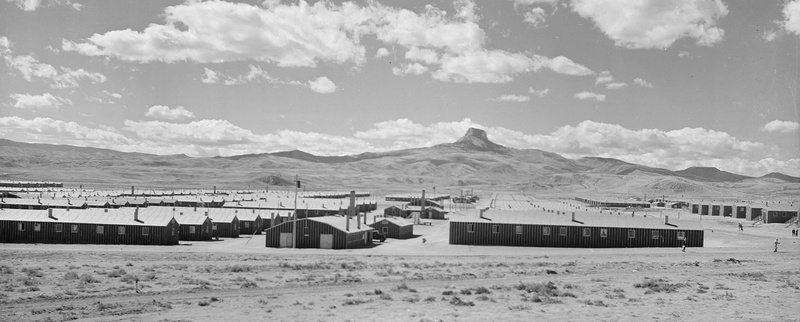

There are editorial cartoons of the day portraying “Japs” as buck-toothed and slant-eyed traitors. The headline of the Cody Enterprise, a local Wyoming newspaper, reads, “10,000 Japs To Be Interned Here.” At the height of its population, with nearly 11,000 Japanese American prisoners, Heart Mountain concentration camp became the third largest city in Wyoming.

Oppenheim said, “There was no fence around the camp when people arrived. It wasn’t until the complaints were coming from the surrounding towns that the fence was put up at their demand.”

Milward L. Simpson, a Cody lawyer and later Wyoming governor and U.S. senator, wrote a letter expressing fear for the safety of the Powell and Cody townspeople if the Japanese in Heart Mountain “go on a rampage.” Calling them sullen and nasty, he also criticized the Nikkei for not all being American citizens. He claimed that at least 25% had sworn allegiance to the Emperor of Japan.

Unlikely Friendship

Ironically, Milward’s son, Alan, became good friends with Heart Mountain Boy Scout Norm Mineta. The Simpson brothers, Alan and Peter, first went to Heart Mountain with their minister to help with a church service. They later attended a Boy Scout Jamboree at Heart Mountain.

Mineta and Alan Simpson were paired to put up a pup tent. Simpson persuaded Mineta to position a moat around their tent so it would drain water on another scout’s tent below. It rained and flooded the other tent, which collapsed. In the book, Mineta said, “I always tell people he was as ornery then as he is today.”

Later, Alan Simpson became a U.S. Senator from Wyoming. Both Peter Simpson and Norm Mineta served in the U.S. House of Representatives. Mineta later became the U.S. Secretary of Transportation under President George W. Bush.

Boy Scout Tragedy

There also were tragedies, like the drowning of 13-year-old Boy Scout Toru Shibata. About 30 boys, ages 9 to 13, went swimming in an irrigation ditch outside of the fence. Shibata tried to swim the ditch, which was about 50 feet across, and drowned.

Oppenheim interviewed some of the former Boy Scouts and remembered, “You could hear in their voices as they spoke of it. It took them back to that moment. They were supposed to go to Yellowstone with the first group. [Instead,] they were pallbearers at the funeral.”

She continued, “[...]when you lose a childhood friend, you come face to face with your mortality. It still clung to them. They were in their seventies when they told the story. They really felt that loss.” There were feelings of guilt, also, since some of the boys had dared Shibata to swim.

Heart Mountain Resisters

On January 22, 1944, the Selective Service reopened to the Nisei. This caused heated debates at Heart Mountain, with some willing to be drafted and others who protested being drafted from behind barbed wire. The Fair Play Committee was formed by the draft resisters.

On March 25, U.S. Marshals arrested 12 men who failed to show up for their induction physicals. In the next few days, 25 more were arrested. By late March, 63 resisters were scattered in jails throughout Wyoming.

The ACLU refused to defend the Heart Mountain Resisters. There were vicious attacks published in the Heart Mountain Sentinel and in JACL’s newspaper the Pacific Citizen. They were called cowards, draft dodgers, and traitors. A mother of one of the resisters committed suicide.

The 63 Heart Mountain Resisters were sentenced to three years in prison. Later, 22 more resisters were found guilty, bringing the total to 85.

Yosh Kuromiya, a 20-year-old college student and resister, in the book remembered, “The stage was pretty well set on the very first day of our trial, when Judge T. Blake Kennedy addressed the 63 of us as ‘You Jap boys— .’ We all looked at each other and didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. We knew then, that things would not go well for us.”

Teaching An American Story

The authors used a reader’s theater format hoping that teachers or librarians would use it with students. In fact, Professor John Benitz at Chapman University in Southern California is currently working on dramatizing the book for a campus performance.

While the authors were collaborating on the Voices book, the U.S. border crisis happened. Thousands of refugees from Central and South America were held in U.S. detention centers, including many children separated from their parents. Both authors see a parallel between Heart Mountain and the border events.

Oppenheim said, “This is an American story, it’s not just a niche story. It’s a story that all people should be aware of. It’s whose ox will be gored next?”

She continued, “We live in a midst of a crisis, where our democracy and freedom, our civil liberties are being nibbled away. [...] So I think that the story has more relevance now than when I originally did it.”

Teaching a Painful Chapter of U.S. History

There are plenty of stories both heartwarming and heartbreaking in Voices. These include the story of Cody high school cheerleader Babe Martoglio who visited Heart Mountain during basketball games. There are letters with humorous drawings about army life from Stanley Hayami to his family and later a photo of his grief-stricken parents receiving the tri-folded U.S. flag after he is killed in action. Finally, there is a glimpse of people’s lives after Heart Mountain.

I wish every public and school library had a copy of Voices as a resource. Sadly, the story of the mass imprisonment of Japanese Americans is not taught enough in schools. The teaching of history to school children is currently in jeopardy nationwide. Some states have chosen to rewrite or even erase the teaching of painful chapters of American history.

This book presents history through the eyes of the people who experienced it with honesty and emotional depth. One cannot look away from events, but are forced to participate. Ultimately, this is a story about what happens when the U.S. Constitution and civil rights are ignored.

Notes:

*Read an excerpt from Unforgotten Voices from Heart Mountain: As American As Apple Pie—Yellowstone here >>

*Oppenheim has a blog with unpublished Heart Mountain stories at joanneoppenheim.com

* * * * *

Unforgotten Voices from Heart Mountain is available for purchase through Amazon (Kindle edition) and the JANM Museum Store (paperback).

© 2023 Edna Horiuchi