Perhaps you know the Heart Mountain, Wyoming, concentration camp for stories of boyhood-friends-turned-congressmen Norman Mineta and Alan Simpson, for the draft resistance of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, for the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center, or for the half dozen or so documentary films about that camp. But as with all of the other camps where Japanese Americans were imprisoned during WWII, there are many unique and lesser known stories that reveal something about life there. Here are ten about Heart Mountain.

1. Severe Climate

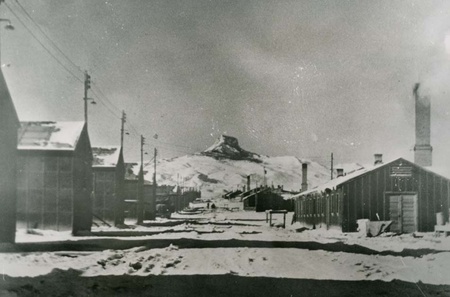

While this is largely subjective, it seems pretty clear that Heart Mountain had the most severe climate of any of the War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps. There are some statistical measures that would support this. It was both the further north and at the highest elevation of any of the WRA camps.1

According to geographer Karl Lillquist, it had the lowest mean temperature (46°), widest annual temperature range (50°), and the shortest growing season (80 days). The lowest recorded temperature was -28° on the night of January 18–19, 1943, part of an eleven-day span during which it reached at least -9° on ten of those days.2

The inmate population, which came mostly from the Los Angeles and San Jose areas, was not used to this kind of weather, though, really no one from the West Coast exclusion zone save for perhaps those from Alaska would have been. Inmates recalled their wet hair freezing into place while walking from the shower to their barrack.

“It was terrible,” remembered Art Okuno in a 2009 interview. “In the first winter there it was like below, thirty below zero, and we’re not used to that winter. They gave us World War I peacoats and gloves, and we had to buy our earmuffs and cap, but it was hard.”

Hal Keimi recalled kids swinging their towels in the air on the way back from the shower to see them frozen stiff by the time they got back.3

The severe weather also had other consequences, as noted in the next two items.

2. Not a Popular Choice

There were two major movements of inmate populations between WRA camps after the initial arrivals: the movements related to segregation following the disastrous loyalty questionnaire in the fall of 1943 and spring 1944, and the redistribution of Jerome’s population when that camp closed in June 1944. Inmates leaving both Tule Lake and Jerome were polled by WRA officials as to which camp they would prefer to be transferred to, which gives us a clue as to how the various WRA camps were viewed by inmates at the time.

Of the five camps “loyal” Tule Lakers would be transferred to, Amache and Minidoka were by far the most popular, followed by Topaz. Heart Mountain finished ahead of only distant Jerome. The Jerome results were even more stark. A preference questionnaire distributed through block managers saw 2,983 choosing Rohwer (no doubt for logistical reasons as that camp was less than thirty miles away), 1,280 choosing Amache, 1,067 choosing Gila River, and only 357 listing Heart Mountain as their top choice.

While we don’t know why Heart Mountain wasn’t seen as a desirable destination by those in other camps, it is hard not to assume that geography and weather were the major factors. The “popular” camps—Amache, Minidoka, and Gila River—were also seen as “good” camps from the administration perspective given their relative lack of unrest and, in the case of Gila, physical conditions that made it the WRA’s “model” camp, so perhaps these things were factors as well.4

3. Coal Conflict

The meager furnishings provided in WRA concentration camps consisted of just one cot per person and a stove that was to heat each barrack unit. Depending on the camp, the stoves were fueled by oil, wood, or, as in the case of Heart Mountain, coal. Given the cold climate, the coal supply and the inmate labor needed to provide it became an issue throughout the life of the camp.

Though stoves were installed when inmates arrived, there was initially an insufficient supply of coal, which, along with the lack of insulation, made for a rude introduction to the camp for the inmate population that came almost entirely from California. “When the coal trains rolled in,” wrote Heart Mountain chronicler Douglas Nelson, “crowds of evacuees rushed down to the tracks, filling every conceivable container with the precious fuel, and then returned to their houses, hoarding the treasure in closets and under beds.”

A distribution system was eventually devised that saw coal delivered to each block, where it would be deposited into a pile. Inmates would race to the pile to scoop up the larger pieces. “If you didn’t get out early enough, get up when the coal truck came and carried some coal, you’d have to go and get the… the crumbs of the coal,” recalled Ted Hamachi. “It’s all loose and it’s real hard to put in.” If you were late, “There would be nothing left except little tiny bits,” wrote Nellie Yae Sumiye Nakamura.5

As with other camps that relied on coal for heating, finding enough inmate workers willing to do the physically taxing and dirty work of unloading the coal cars as they arrived by train for the meager WRA wages proved to be a challenge throughout. During the first winter of 1942–43, the administration leveraged the fact that “Californians [were] terrified at prospect of Wyoming winters,” to secure enough workers. Later, block chairmen took turns unloading coal to insure that there would be sufficient supply.

The arrival of over 1,300 inmates from Tule Lake temporarily eased the labor shortages in the fall of 1943, as the newcomers took coal jobs at least for a time. But in the fall of 1944, the coal situation came to a head, as inmate workers refused to unload the coal cars, leading to the inability to producehere being no hot water in Blocks 9 and 22 for three days at the end of September.

As Community Analyst Asael T. Hansen observed, there would be no Tule Lake arrivals to save them this time. The impasse was finally broken by groups of “volunteers” from each block—some three hundred in total—who gathered on October 8 to unload twenty cars of coal. Later, a plan to rotate workers from other departments to unload coal led to enough being unloaded to get them through their final winter at Heart Mountain.6

4. The Washingtonians

Heart Mountain’s inmate population was largely an urban one and largely Californian, with about half coming from Los Angeles and much of the rest coming from San Jose and other parts of Santa Clara County as well as one group from San Francisco. But about 900 people—not quite ten percent of the initial population—came from mostly rural areas of southern and central Washington state including Wapato, Toppenish, and Yakima, via the Portland Assembly Center.

But in addition to this initial group, another 700 or so from Washington came as part of the group of “loyal” Tule Lake inmates in the fall of 1943, nearly half of the total who came from Tule Lake. Adding another couple of hundred Washingtonians who came via transfer from other camps or Issei parolees from enemy alien internment camps, over 1,800 people from the state of Washington were held at one time or another at Heart Mountain.7

While the Yakima Valley group may have had an easier adjustment to the physical conditions at Heart Mountain—Yakima chronicler Thomas H. Heuterman wrote that “Ironically, the site… was reminiscent of the bleak Yakima Valley decades before, when settlers developed the dusty land”—they also found themselves as fish out of water surrounded by the urban zoot suiters and hipsters from California.

“And what really struck us was to arrive here into this group of Japanese that looked so unfamiliar,” recalled Wapato’s Marjorie Matsushita Sperling. “They had the particular haircuts, they were rowdy, they were boisterous and very different.” But despite these differences, there didn’t seem to be much locality-based conflict at Heart Mountain as was found in other camps where urban and rural populations mixed.8

5. Double-Sized Blocks

An odd quirk of Heart Mountain was that the blocks were twice the size as those at other WRA camps, with 24 barracks per block versus 12 or 14 at the other camps. In practice, there really wasn’t much difference, as each half block at Heart Mountain was laid out in more or less the same fashion as full blocks at other camps: two rows of six barracks facing each other, with a mess hall and an H-shaped bathroom/laundry building in between.

To distinguish between the two half-blocks, the unit closer to the mountain was referred to as the “upper” unit, while the other was the “lower” one. There were 19½ blocks at Heart Mountain, the equivalent of 39 blocks at other camps. Blocks were numbered from 1 to 30, with not all numbers used; Block 7 was the half-block.9

References

1. Two of the assembly centers—Portland and Puyallup—were further north, but being closer to the coast, had much milder climates. Two of the largest Justice Department run camps that held interned Issei, Missoula and Fort Lincoln/Bismarck, were also further north and also had severe climates.

2. Karl Lillquist, “Imprisoned in the Desert: The Geography of World War II-Era, Japanese American Relocation Centers in the Western United States” (Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, September 2007), 103, 524–25.

3. Art Okuno Interview by Kirk Peterson, Segment 20, Las Vegas, Nevada, September 1, 2009, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Archive; Hal Keimi Interview by Brian Niiya (primary), Emily Anderson (secondary), Segment 8, Los Angeles, California, February 5, 2019, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Repository.

4. James M. Sakoda, “The Segregation Program in Tule Lake,” Dec. 1, 1945, pp. VIII2–3, Japanese American Evacuation and Relocation: A Digital Archive (JAERR), Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder R 20.90:3; Rachel Reese Sady, “Summary of Closing Procedures,” July 15, 1944, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder N1.05.

5. Douglas W. Nelson, Heart Mountain: The History of an American Concentration Camp (Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin for The Department of History, University of Wisconsin, 1976), 25; Ted Hamachi Interview by Kirk Peterson, Segment 12, West Covina, California, March 4, 2010, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Archive; Shizue Siegel, A Century of Change: The Memoirs of Nellie Yae Sumiye Nakamura from 1902 to 2002 (Self-published, 2002), 149.

6. [Community Analysis Section], “Heart Mountain Community: I. Moving In: August, 1942 to January, 1943,” JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M2.40; [Community Analysis Section], “Community Organization,” JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M1.00; [Community Analysis Section], “Heart Mountain Community: II. Being Sorted,” p. 17, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M2.40; Asael T. Hansen, Weekly Report for Sept. 29–Oct. 5, 1944, pp. 4–5, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M2.37:1; Asael T. Hansen, Weekly Report for Oct. 6–12, 1944, pp. 3–4, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M2.37:1; Asael T. Hansen, Monthly Report for Oct., 1944, p 1, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M2.37:1.

7. Figures from the Heart Mountain Final Accountability Roster (FAR).

8. Thomas H. Heuterman, The Burning Horse: Japanese American Experience in the Yakima Valley, 1920-1942 ;(Cheney, Wash.: Eastern Washington University Press. 1995), 127; Marjorie Matsushita Sperling, interviewed by Tom Ikeda, Segment 17, Feb. 24, 2010, Culver City, Callifornia, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Archive.

9. [Asael T. Hansen], “The Heart Mountain Community,” n.d. [1945], p. 4, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M1.00; George Nakagawa, The Cross on Castle Rock: A Childhood Memoir (Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse, Inc., 2003), 71; Lillquist, “Imprisoned in the Desert,” 98.

*This article was originally published in Densho's Catalyst on July 26, 2023.

© 2023 Brian Niiya