What images come to mind when we think of the wartime experience of Japanese Americans? For many, the photographs produced by Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams or Toyo Miyatake come to mind, with their unique portrayals of the human condition. Yet equally powerful and moving are the representations of the incarceration experience produced by the diverse crew of visual artists who worked in camp, including such figures as Miné Okubo and Chiura Obata.

One artist who created striking images of confinement was Kango Takamura. A painter and photographer, Takamura was one of the few Issei to break into Hollywood before the war, when he was a retoucher for RKO pictures. During the war, he documented his internment at Santa Fe Internment Camp through dozens of watercolors, offering a rare view into the experience of Issei internees there. Afterwards he was released and sent to Manzanar, where he created hundreds of paintings portraying life in camp.

Kango Takamura was born in Ozumachi, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan on March 25, 1895. Takamura’s childhood was eventful; at age ten, he lost his mother, leaving him to be raised by his father and grandmother. As a student, he encountered several European and American instructors who lectured at his school and preached the Gospel. His early exposure to foreigners piqued Takamura’s curiosity about the larger world and about Christianity.

At age sixteen, Kango and his brother Tatsumi were taken along by their father to Hawaii. There Kango enrolled in Trinity School while he searched for work. While in Honolulu, Kango began to explore his interest in the visual arts. After leaving school, he worked as a self-employed photographer. He continued to indulge his love of drawing and painting as a volunteer at Honolulu’s YMCA and St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, where he taught art classes for children.

In August 1918, Takamura sailed to Japan, where his father had relocated. He returned to Hawaii a year later. He later claimed that he fell ill during the global influenza epidemic, and spent six months convalescing in a hospital.

In April 1921, Takamura moved to the mainland, settling in Los Angeles. He enrolled in the Chouinard School of Art for two years, during which he developed a portfolio as a painter and photographer. To make ends meet, he found employment as an assistant to Chikashi Tanaka, a Little Tokyo studio photographer (whom he described as his future brother-in-law).

In 1924, Takamura left Los Angeles and sailed to New York City, where he found a job with Famous Players-Lasky Pictures, a parent company of Paramount Studios. Although he initially applied to be a cameraman, movie directors told him he was too short to carry a camera, and instead hired him as a photo retoucher. He was chosen out of one of ninety applicants.

While in New York City, he courted Setsuko Fujino, a biwa instructor who had immigrated from Japan as a teenager in 1913. She was initially married to Koichi Wada, and the couple had one daughter, Jean Miho Wada, before divorcing in 1920. Setsuko and Kango married on August 17, 1927. A year later, in 1928, Takamura was invited by Paramount’s Hollywood studio to organize their still retouching department, and moved to California.

In 1930, during the Great Depression, Takamura left his job at Paramount. After a six-month pause, during which he travelled with his wife, he was hired as a photo retoucher at RKO Pictures. In the following years, Takamura would work on several noteworthy pictures, including RKO’s 1933 film King Kong.

On July 19, 1935, Kashu Mainichi published a photograph of Kango with actor Tetsu Komai at a party. On November 14, 1940, the Rafu Shimpo reported that Kango’s daughter Jean married Rafu Shimpo English editor Togo Tanaka.

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and U.S. entry into the war, life became tense for Takamura. Many of his Issei friends lost their jobs. Although Kango remained with RKO Pictures, and his bosses promised to protect him, he faced harassment from several employees. In February 1942, the FBI arrested him.

According to Takamura, he was arrested because he was treasurer of a Los Angeles Japanese archery club, the Butoku-Kai. Although his position as treasurer was mostly honorific, a benefit event hosted by the club for visiting Japanese military officer served as evidence of his potential “disloyalty.”

During the meeting, the officer enticed Kango into selling him an RKO movie camera, which he agreed to do after the officer left for Japan. Although the officer was unable to request the camera from Takamura after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI used the conversation to justify his arrest.

Whatever the case, Justice Department agents whisked Kango away to the LA County Jail, where he spent a night before boarding a bus bound for the Tuna Canyon Detention Camp. Once at Tuna Canyon, Kango faced a barrage of questions. When an FBI agent asked Takamura which side he wanted to win the war, he responded:

“I do not want either to lose. To see them at war is like watching my mother and my father fight and quarrel. I wish they would stop without harming each other. My immediate family is in the United States – my wife, my daughter, my son-in-law, my granddaughter. They are American citizens. My father and other relatives are in Japan. This war is a personal tragedy for me no matter what.”

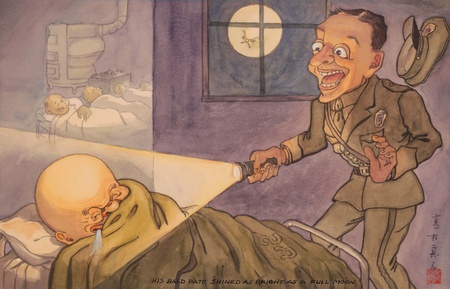

After several weeks at Tuna Canyon, Takamura was confined at the Santa Fe Internment Camp in New Mexico. Takamura described conditions at Santa Fe as rigid; guards with flashlights came in three times each night to check on the inmates. After weeks of such inspections, an internee spokesman finally approached the guards and declared, “None of us would escape or try to escape even if you paid us.”

From then on, the guards ceased their rounds. While at Santa Fe, Takamura had time on his hands. He produced numerous watercolors, including one brutal scene of guards waking an internee.

He later stated that he made his art in “cartoon-like fashion” to avoid having his works confiscated by camp authorities. Some of Kango’s watercolors from this period evoke Japanese manga and even popular cartoon characters such as Popeye the Sailor.

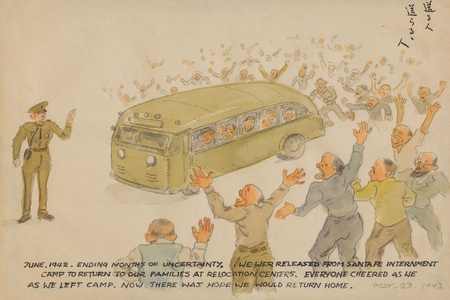

After four months at Santa Fe, Takamura was released and sent to Manzanar, where his family was confined. There, Takamura again concentrated on art. He later said it was the busiest time of his life: “Usually when I worked in the movie studios I would work eight hours. But every day at the camp, I worked ten hours.”

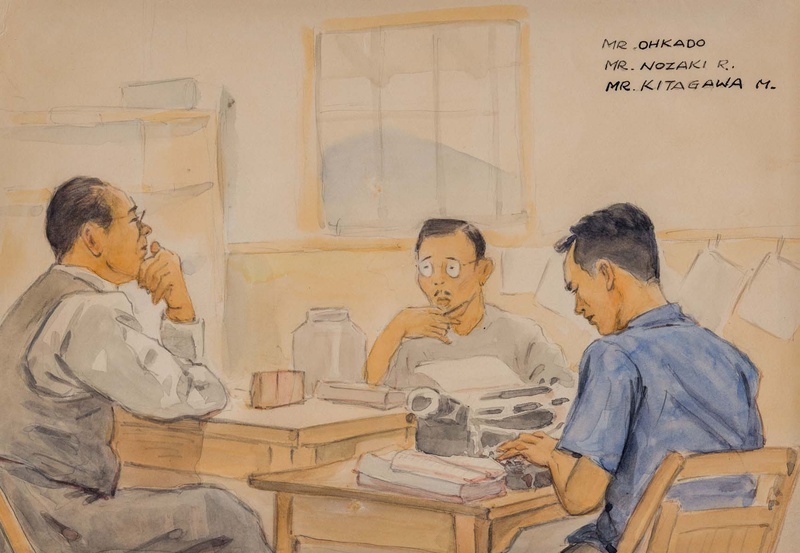

Takamura was hired as a Staff Artist in the Visual Education department, where he worked with director Kiyotsugi Tsuchiya. Takamura helped establish a visual education museum that displayed artwork and artifacts. He also helped prepare the Museum’s exhibit at Christmas 1942, during which he displayed his artwork from Santa Fe and created schoolroom exhibits.

In 1943, along with Tsuchiya and Toyo Miyatake, Takamura conducted explorations for artifacts of Indian life around the campsite. When director Tsuchiya left camp in 1944, Takamura took over as director of visual education. He also taught painting classes, and helped organize the camp YMCA.

In addition to his art, Takamura found comfort in religion. In 1942 he joined the Episcopal church, and was baptized by Bishop Charles Reifsnider.

One less-known story about Kango’s life at Manzanar was his defense of his son-in-law Togo Tanaka during the “Manzanar Riot.” On the night of December 6, 1942, a group of Manzanar residents gathered to hear speeches by several protestors, including Harry Ueno, who decried corruption among the camp administration.

Enraged, the group set out into the community to identify inus (collaborators) such as JACL leader Fred Tayama, who was badly beaten by dissidents. Several rioters searched the barracks looking for Togo Tanaka—who had in fact been spirited away by government officials to a safe haven in Death Valley.

As the mob approached Takamura’s barrack, he asked what they wanted. A dissident cried that they were going to kill Tanaka as an inu, and demanded that he be turned over to them. Takamura refused to divulge his son-in-law’s whereabouts. He declared that Tanaka’s work as camp documentarian did not make him an inu, and invited the mob to look through his files for proof of collaboration. (Tanaka later admitted that the family had taken the precaution of destroying any papers they considered compromising, notably a correspondence Tanaka had struck up with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt).

Restless and impatient, one man shouted that Tanaka’s family should be killed because they were related to an inu, whereupon Setsuko scolded the mob members. After a tense few minutes, military police arrived and the mob dispersed.

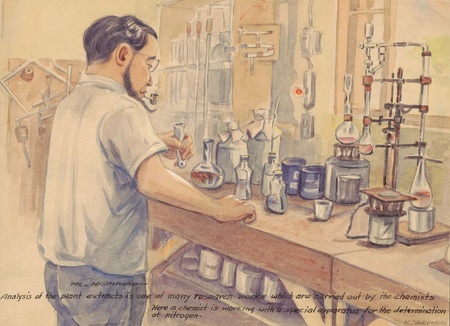

Following these events, Tanaka and his wife left Manzanar, and Takamura’s life became more peaceful. He spent much time drawing sketches and painting watercolors of everyday life in camp. One unique subject of Kango’s brush was the Manzanar guayule project. Takamura made several watercolors depicting the scientists of the project at work in their lab, and provided beautiful diagrams of the anatomy of the guayule shrub.

The Takamuras remained at Manzanar until September 1945, shortly before the camp closed. According to Togo Tanaka, they remained, at least in part, because of Kango’s strong friendship with Camp director Ralph Merritt. Merritt (who had invited famed photographer Ansel Adams to Manzanar) admired Takamura’s art and commissioned him to paint scenes of Manzanar. In his last weeks in camp, during summer 1945, Takamura taught a series of special children’s summer art classes.

After the war’s end, Takamura was fortunate enough to return to his old job at RKO Pictures, where he worked until the company closed in 1959. For the December 20, 1948 issue of the Rafu Shimpo, journalist Alice Sumida interviewed Takamura about his career at RKO pictures and his views on the film industry. In November 1954, Takamura finally became a naturalized U.S. citizen. In his retirement, Takamura continued to engage with artists. For Nisei Week on August 4, 1959, Takamura performed a musical number with fellow artists Michio Takayama and Taro Yashima at the Tenrikyo Gallery. In May 1960, Takamura invited famed Japanese watercolor painter and sumi-e artist Shoun Igarashi to his Los Angeles home. Takamura arranged for Igarashi to give a series of lectures at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, a church which Takamura regularly attended.

In later years, Takamura was invited to display his wartime art. In October 1973, he exhibited several of his Santa Fe pieces at branches of the Sumitomi Bank in Los Angeles. One of Takamura’s paintings from Santa Fe was featured on the cover of the Fall 1974 issue of Amerasia Journal.

The issue, which featured Art Hansen and David Hacker’s article “The Manzanar Riot: An Ethnic Perspective,” helped rekindle interest in Takamura’s camp artwork. With the encouragement of his pastor, Rev. John Yamazaki of St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, on June 21, 1974 Takamura donated his painting collection to UCLA’s Young Research Library. A few months later, UCLA Asian American Studies Center published a pamphlet on the Takamura collection.

Meanwhile, Takamura provided interviews and oral histories on his camp experiences. In March 1981, journalist Toby Smith profiled Takamura in the Albuquerque Journal as part of an extended story on the Santa Fe Internment Camp. In the article, Takamura spoke about his time at Santa Fe, and how his art saved him amid his hardships in camp. Art scholars Deborah Gesenway and Mindy Roseman likewise dedicated a chapter to Takamura in their book Beyond Words: Images from America’s Concentration Camps.

Kango Takamura died in Los Angeles on January 17, 1990, not long before his 95th birthday. In the years since his death, his camp art has become ever-more celebrated, notably following its inclusion in The View from Within, the traveling camp art show organized in 1992 by the Japanese American National Museum, which played various venues. Takamura’s artwork from Santa Fe, Our Roommates, was likewise reproduced in an article in the Los Angeles Times magazine in 1992.

Takamura’s work was included in the 2007 exhibition From 12/7 to 9/11: Lessons on the Japanese American Internment, at Young Research Library, and later the 2022 camp art show No Monument, at New York's Noguchi museum. While Takamura’s photography garnered less attention, his 1927 photo of his wife was featured in the 1989 show Japanese Photography in America 1920-1930 at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC., and was reproduced in the Washington Post.

Not only were Takamura’s watercolors powerful in their imagery, but as one of the few artists working in the Department of Justice camps, he left important artifacts that show what Issei internees endured. His brilliant depictions of life at Manzanar also documented some of the happier moments in camp while visualizing the banality of camp life. In sum, his body of work remains an iconic part of Japanese American art history.

© 2023 Jonathan van Harmelen, Greg Robinson