Takeshi Furumoto is an activist in Japanese American organizations and communities, a Vietnam War veteran awarded the Bronze Star, and a successful businessman. His upbringing, family background, and life experiences have added up to a complex identity as a self-described "Kibei Nisei and a half," a full-fledged Nikkei, and an American.

Born in 1944 in Tule Lake War Relocation Center, he moved to Hiroshima, Japan with his parents after the war and attended Japanese schools. In 1956, he and some family members were allowed to return to the United States and settled in Los Angeles. After completing his education in California and serving as an intelligence officer in the U.S. Army in the Vietnam War, Furumoto moved to New Jersey in 1971. In 1974, he and his wife, Carolyn, launched Furumoto Realty which specializes in placing Japanese executives in homes in the tri-state area (New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut). In 2024, Furumoto Realty will celebrate its 50th year in business.

A Humanitarian who Honors History and Connects People

Furumoto and his wife campaigned tirelessly for the passage of Fred Korematsu Day in New Jersey, which was signed into law on January 30, 2023. This honors Korematsu, an American who was not allowed to serve in the U.S. military due to his Japanese ancestry. When Executive Order 9066 was issued in February 1942, Korematsu refused to move to an incarceration facility because he thought his civil rights were being violated.

Among Furumoto’s other civic and humanitarian achievements, he is a founder and currently an Honorary Chairman of New York Hiroshima-Kai, an association that cultivates mutual friendship among people in Hiroshima and the Northeastern U.S. (New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts). On August 5th each year, Hiroshima-Kai hosts a peace memorial event in New York City to commemorate the atomic bomb victims in Japan. Furumoto’s parents’ families in Hiroshima had been devastated by the attack.

He is a Life Member of the Japanese American Veterans’ Association, helping to organize events in the New York City area, and is also a founding member of Digital Museum of the History of Japanese in New York. This museum collects and shares the stories of thousands of Japanese and Japanese Americans who have lived in New York since the first Japanese official delegation arrived in 1860.

Family Roots

“I am a son of a migrant farmer,” said Furumoto. “Our family history in the United States started 112 years ago when my grandparents (my father’s side) came to the U.S. in 1911 from Nishihara in Hiroshima prefecture to Florin, California near Sacramento.” Furumoto’s father, Sam Kiyoto Furumoto, then three years old, was left behind in Hiroshima to be cared for by his grandparents. In 1921, at age 14, Sam Furumoto rejoined his family in California. His parents could not afford to support Sam in addition to his three younger siblings, so he found work as a migrant farmer picking strawberries on leased land.

Due to the Japanese Exclusion Act, Issei (first generation Japanese) were prohibited from owning real estate, so Sam was never able to start a farm of his own. Instead, he started a wholesale produce business. “He had street smarts, so in 1938, he started Oka Produce with a partner in downtown Los Angeles,” said Furumoto. Oka Produce grew to employing 26 workers, but the business was confiscated when President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942.

Incarcerated in Rohwer, Arkansas and Tule Lake, California

With the signing of Executive Order 9066, Furumoto’s family and 120,000 other Japanese and Japanese Americans were forced to leave their jobs, sell or abandon businesses and farms, and leave their homes. “My parents and my four older sisters were living in Boyle Heights, East Los Angeles, when they were forcefully incarcerated,” recalled Furumoto.

Initially assigned to temporary facilities at Santa Anita Park, a racetrack in Arcadia, California, his family was later incarcerated in war relocation centers at Rohwer, Arkansas and then at Tule Lake, California, which became known as the “No No Camp”.

“In the spring of 1943 at Rohwer War Relocation Center, my parents answered, “No No” to Questions 27 and 281 in the so-called ‘Loyalty Questionnaire.’ To Question 27 ‘Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States . . .wherever ordered?’ they replied ‘No’ because they had lost everything and had been forcibly imprisoned without due process because of their ethnicity. To Question 28 ‘Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attack by foreign or domestic forces and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor . . . ,’ my parents answered ‘No’ because their parents were living in Japan, and if they answered, ‘Yes’ they feared they would never ever be admitted to Japan to visit their parents.”

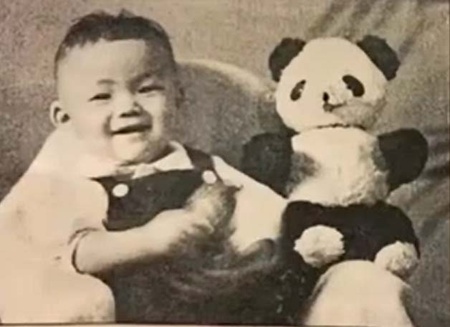

Furumoto continued, “Anybody who answered ‘No No’ to these questions was considered disloyal to the United States and was sent to Tule Lake Segregation Camp. In the spring of 1944, my family was sent to Tule Lake. On October 20, 1944, I was born there.

“In December 1945, we were released and returned to my father’s home country in Hiroshima, Japan. We boarded the American Military Transport Ship called USS Gordon, along with about 4,000 other Japanese and Japanese Americans, bound for Yokosuka, Japan.”

His American-born mother lost her U.S. citizenship. His father was a Japanese citizen. “In a case of tacit deportation, they were not allowed to come back to the United States,” explained Furumoto. He and his siblings were able to retain their U.S. Citizenship because they had not turned 18 at that time.

His parents had compelling reasons to return to Japan – to help their families who had been devastated by the war. “Our grandparents on both my father’s and my mother’s sides were victims of the atomic bomb dropped by the U.S. on August 6, 1945. My mother’s family lived only a couple of miles from the epicenter near Danbara, a train station in Hiroshima. My father’s family lived in Nishihara, about seven to eight miles from the epicenter.”

“My parents, siblings, and I settled in Nishihara, near my father’s family. I attended Gion Elementary School until May 1956, where I finished 5th grade.”

Returning to America

Furumoto and his family wanted to return to the U.S., but because his mother had lost her U.S. citizenship and his father was considered an alien by the U.S. government, it took a “legal loophole” for everyone to return over several years.

“In 1952 when my oldest sister, Mary (Katsumi) was 19, she came to the United States first,” explained Furumoto. “Mary worked hard to bring my second oldest sister, Lillian (Kyoko) in 1953. When Mary turned 21 in 1954, she was able to legally recall our father. In 1955, when my third oldest sister, Margie (Yasuko) graduated from high school in Hiroshima, she joined Mary and our father in U.S. In 1956, my mother, my fourth sister, Kay (Kayoko), and I were finally reunited with our family in California.”

His family settled in South Central, Los Angeles. “We were steered to live in undesirable areas because of our race,” noted Furumoto.

A brief sojourn to New York City, then a return to Los Angeles

“In May 1959, our family briefly moved to New York City to help my aunt (my mother’s younger sister) when she opened Aki Japanese Restaurant near Columbia University. It was the second Japanese restaurant to open in New York City,” recounted Furumoto.

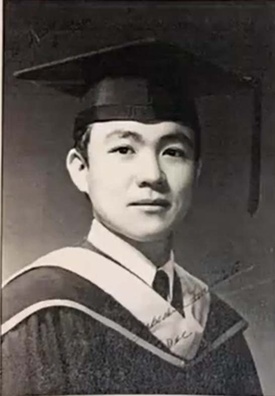

The family returned to Los Angeles in August 1959, where he attended and graduated from Audubon Junior High School and Mt. Carmel High School. He then attended the University of California at Los Angeles, graduating in 1967 with a degree in business administration.

Military service in Vietnam

In February 1968, Furumoto’s life took yet another turn when he volunteered to serve in the U.S. Army. After attending Officer Candidate School at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, he was commissioned as an Intelligence Officer in February 1969. He was then sent to the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center in Monterey, California to study Vietnamese and then to the U.S. Army Intelligence School at Fort Holabird in Baltimore, Maryland.

Furumoto served in Vietnam from February 1970 to February 1971. “I was stationed at Duc Hue, a rural district in the Mekong Delta, as an advisor to the Republic of Vietnam National Police and as a U.S. Counterinsurgency Advisor, as well as Officer in charge of U.S. District Intelligence and Operations Coordinating Center,” he recounted. For his meritorious service in a combat zone, he was decorated with a Bronze Star medal in January 1971.

Overcoming the effects of a terrible war -- and building a successful new life

“I came home in February 1971 with a serious case of PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) and suffering from the effects of Agent Orange, a chemical toxic defoliant. I am a disabled Vietnam veteran,” recounted Furumoto. Due to PTSD, he wanted to isolate himself from his loved ones, so he left Los Angeles and moved to Fort Lee, New Jersey in May 1971.

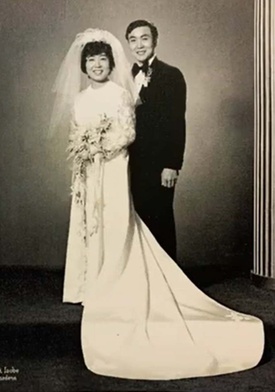

In June 1972, he married his wife Carolyn. She was from Los Angeles, and they had met in 1968 while Furumoto was attending Officer Candidate School. One connection they had was her parents had gotten married in Tule Lake. Also, her father was born in California and grew up in Higashihara, Hiroshima prefecture, situated next to the village of Nishihara where Furumoto had lived as a boy.

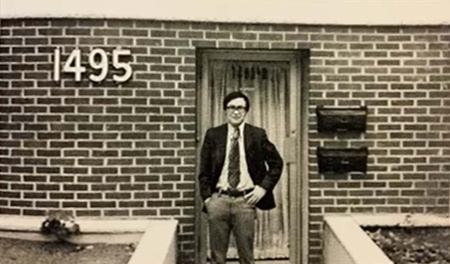

“After our marriage, we had a difficult time, but she had nursed and supported me during my difficult years. I was not able to hold my jobs due to PTSD,” said Furumoto. “In June 1974, we started Furumoto Realty in Fort Lee, New Jersey, starting in a $100/month basement office. Our real estate office was the first Japanese American brokerage company on the East Coast.”

In the 1970s and 80s, Japanese companies began opening offices in New York City and sending its executives to the U.S. With Furumoto’s Japanese language skills and knowledge of Japanese customs and culture, he was able to build relationships with Japanese clients and help guide them to purchase or rent homes in New York and New Jersey.

As Furumoto approaches his 80th birthday in 2024, he remains vibrant, positive, and committed to furthering Japanese American interests and causes and making sure that we remember the stories of courage and “gaman” from Japanese American people. On Saturday, May 13, 2023, Furumoto once again wore his military uniform and marched in the second annual Japan Day Parade in New York City, along with Grand Marshal and former Olympic star, Kristi Yamaguchi.

Note:

1. “Question 27 and 28,” Densho Encyclopedia (Aug. 24, 2020)

*All photos are from screenshots from “Takeshi Furumoto Talk Event at Hunter College,” courtesy of Tak & Carol Furumoto, unless noted.

© 2023 Karen Kawaguchi