Cruise ships serve as migrant ships to South America

Half a century has passed since the last immigrant ship arrived - "The Equator Festival and the arrival in Santos were experiences that only those who had been on the ship could experience. It was a turning point in my life. I knew the half-century ceremony for the last immigrant ship would come," said Kazuo Koike, with deep emotion in his opening remarks at the 50th anniversary ceremony of the Nippon Maru Shipmates Association.

For immigrants, entering Santos is not just a simple landing like for tourists. Just as it has been said since before the war, "Santos, ready, set, go!", it has been recognized as a starting point for them to leave behind all their Japanese family history, academic background, and career, and to start afresh from scratch.

The passenger ship Nippon Maru, known as the "last immigrant ship," left Japan on February 14, 1973, and arrived at the port of Santos on March 27. Over the course of 65 years, about 250,000 people had migrated by ship from the Kasato Maru, but this ship marked the end of that era.

A ceremony to celebrate the 50th anniversary was held on April 2nd at the Brazilian Japanese Senior Citizens' Club Federation salon in the Liberdade district of São Paulo, with around 50 people, including their families, spending the day in a relaxed atmosphere.

Until about 10 years ago, the "Shipposha-kai" was held almost every month. This event is unique to immigrant communities, but it has become rare to hear of it recently. The same goes for the "Dokyo-kai" for people who came from the same colony or settlement. The aging and decline of the Issei is fundamentally changing the nature of the colony.

The year 1973 marked the final stage of Japan's period of high economic growth. In 1960, the cabinet of Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda announced the "Income Doubling Plan," which aimed to more than double the gross national product (GNP) over a ten-year period and achieve living standards and full employment on a par with those of Western countries.

The Meishin Expressway opened in 1963, and the Tokaido Shinkansen in 1964, establishing a high-speed transport network between major cities. The decade leading up to 1963 was the peak of postwar immigration, after which there was a rapid decline.

This is no surprise. Japan successfully hosted the Tokyo Olympics in 1964 and the Osaka Expo in 1970. During that time, Japan's GNP surpassed that of West Germany in 1968, making it the world's second largest economic power after the United States.

Japan had achieved astonishing economic growth in just over 20 years since its defeat in the war, and was called the "Miracle of the Orient" with admiration and respect from around the world. This was a time when other countries began to take Japan as a model.

Brazil was one of those countries, and 285 people from Japan decided to emigrate there in 1973. Usually, an "immigrant ship" is a cargo-passenger ship, but the Nippon Maru (the first one) was a "cruise liner" that took the wealthy around the world.

However, of the 431 people on board, 285 were immigrants, the majority. So it may be fair to call it the "last immigrant ship." After this, the era of "airplane immigration" began.

I asked some of the people at the shipmates' meeting a rather nasty question: "Why did you decide to leave Japan, which was in the midst of a long period of advanced economic growth, and move to Brazil?" The answer I got was, "I wonder why. Those who thought it was no good returned to Japan early on. Those who are still here are those who managed to make a living. Or those who have a reason for not being able to return, or those who don't want to return, I think," in a straightforward voice.

Satoshi Urano (75, from Tokyo), a member of the association, said, "For the first 10 years, we were doing our best just to survive and couldn't attend meetings like this. Many of our generation are industrial immigrants, so even if we weren't hugely successful, many of us are able to live at a decent level. Maybe that's why it's so easy to get together like this."

Some say there is a difference between agricultural migrants, many of whom faced extreme conditions in the countryside where life was at risk, and industrial migrants, many of whom had a trade and lived in cities from the start.

No matter who I asked, I was told that "more than half of the people on the ship returned to Japan" and "the majority of the people who came after us on planes returned, not just half." If we waited another 10 years, Japan would be in the midst of its postwar bubble economy and the start of the dekasegi (a backflow of foreign workers) movement to Japan. That's the kind of era we live in.

"I almost missed the boat in LA."

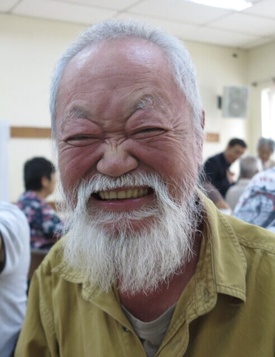

"At that time, I almost missed the boat in Los Angeles and caused a lot of trouble to everyone," says Kenjiro Ikoma (74 years old, from Mie Prefecture), who is now a famous ceramic artist, laughing out loud as he shares this outrageous episode. It seems that he had a "mischievous" time in his youth.

When the Nippon Maru was docked overnight in the port of Los Angeles, a companion who was about 10 years older than him invited him to "go ashore and have fun!" and, being youthful, he got carried away and ended up staying overtime.

Ikoma said, "We were really struggling after missing the boat, not knowing left from right and not knowing English. But luckily the owner of the restaurant was kind enough to call us a taxi, and we made it just in time." A fellow passenger next to us immediately interrupted, "Actually, they didn't make it that time. The boat was waiting for them even though the departure time had passed."

Ikoma then laughed and said, "I'm really sorry. I apologized to everyone after I got on board and was suspended after that." Looking back on it now, it's a fond memory from his younger days.

Ikoma, who seems to be all energetic, also said something meaningful: "People change when they cross borders." It was something that fellow cruiser Umeda Masayuki said, and Ikoma says he has personally experienced it.

"When I was working for a company in Japan, I was the kind of person who never stood out no matter what I did and always seemed to lose out to the people around me. But that changed through my various experiences in Brazil. Of course, my true nature as a Japanese person hasn't changed. It's better to move alone," he advised.

When asked what kind of experience he had, he first mentioned a baptism he received immediately after arriving in Brazil. While undergoing training at the relocation center, he went shopping at a nearby supermarket and "suddenly had a pistol pointed at my side. I raised my arms and said in Japanese, 'I give up, I give up,' intending to surrender, but this surprised the bandit, who then stole some money from the register nearby and ran away."

He immediately returned to the relocation center and told them about his experience, which frightened him when they said, "Maybe they heard my 'I've had enough, I've had it' as 'Mata Mata (Kill me, kill me)." "I get attacked a lot. I think I've been attacked about 10 times," he said, sharing his shocking story.

In addition, Tsutomu Baba (74 years old, from Yamaguchi Prefecture) told the surprising story of "celebrating my birthday twice on the ship." He nodded vigorously and said, "We crossed the date line on February 20th, which was my birthday. So my birthday was two days in a row, before and after the date change. I thought that the luck that had been bad in Japan had finally turned around. I was able to come to Brazil and have descendants. I consider it a success."

Kuniharu Tada (78 years old, from Tokushima Prefecture) said, "February 14, the day we set sail, happened to be the day the dollar moved to a fully floating exchange rate system. So when we set sail, 1 dollar was worth 274 yen, but the next day the yen strengthened sharply. Thanks to that, people who brought yen in bulk must have made a profit. If you ask how I remember 274 yen, it's because of "funayoi" (274)."

Michio Higuchi, who attended the shipmates' reunion for the first time in 40 years, said with a big smile, "Everyone's faces have changed so much I don't recognise them, but it's nostalgic because we were shipmates." He is a somewhat unconventional immigrant, having spent 30 years working in Japan for 11 months and taking a vacation in Brazil for one month, before finally settling down in Brazil in October of last year. "There are more changes here than in Japan, so it's more interesting."

*This article is reprinted from the Brazil Nippo (April 18, 2023).

© 2023 Masayuki Fukasawa