I get it. I understand. Traveling to someplace you’ve never been, where the culture and language is foreign to you, can be challenging. I know lots of Americans–including some Japanese Americans–who’ve either been hesitant to go to Japan, or who’ve gone and struggled to adjust to the oddly familiar, yet unfamiliar, sights, sounds, tastes and culture. It can be discombobulating.

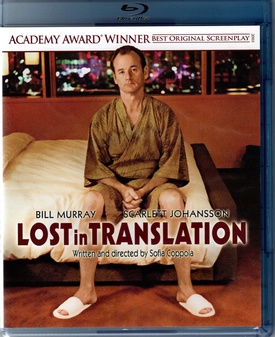

That’s the opening premise of a movie that was released 20 years ago: Lost in Translation.

The film was written and directed by Sofia Coppola, and it was well-received critically and at the box office. Coppola even won an Oscar for best original script the next year. The plot of the film is about two Americans, a fading older movie star played by Bill Murray and a young woman right-out-of-grad-school played by Scarlett Johansson who is left to wander Tokyo on her own because her photographer boyfriend who she traveled with is gone on assignment a lot of the time during the movie. Both characters’ relationships are failing. Murray has sad and disconnected phone calls with his wife and so does Johansson with her boyfriend.

The two meet each other out of boredom, ennui and loneliness at the Shinjuku Park Hyatt Hotel, which is a character all its own. The film is about their relationship, which is emotional and not sexual, or at least, not sexually fulfilled. They kiss as Murray’s character leaves for the airport to fly back to the US, which serves as a happy ending of sorts while Johansson is left in Tokyo waiting for her boyfriend.

Coppola has said that the movie was her love note to Tokyo. Lost in Translation was released the same year as two other movies set in Japan, The Last Samurai, a nonsensical historical representation starring Tom Cruise, and Kill Bill Volume 1, which was partly set in Japan and featured a pretty great, violent fight scene in a Tokyo restaurant that I got to eat at this past spring. But those two movies were not realistic representations of Japan or of Tokyo. Lost in Translation wants to show the Tokyo which Coppola was familiar with and had visited many times.

Because of the 20th anniversary of the release on September 12th there have been a few articles looking back on both the impact of the film and some of the issues that linger in the way Lost in Translation portrayed Tokyo. The Japan Times ran a thoughtful feature story that interviewed some of the Japanese cast and crew that worked on the film, and how they felt some of the script was insulting. (The link might require a subscription, though maybe the JT allows a few free articles before putting up their paywall.)

Visually, the movie does a great job of showing a lyrical Tokyo with colors and long shots and and you can see the urban landscape in a way that’s downright poetic. But it shows some of the problematic cultural things that Americans assume are what Japan is all about like young people with pink wigs getting wasted in karaoke bars–although having a drunk Japanese dude screaming the Sex Pistols’ punk anthem ”God Save the Queen” is pretty funny.

I remember liking Lost in Translation when it came out, but also feeling uncomfortable about some of it. I watched it recently on Blu-ray and I was mildly surprised to find that I didn’t hate it but have to admit that there are a couple of scenes that bother me a lot more than back then, partly because I know more about the way stereotypes can be insidious sources of hate, including anti-Asian hate.

In one scene Murray, who is in Japan to tape commercials for Suntory whisky, is sent a prostitute to his hotel room and the way Japanese people mispronounce English becomes a running gag. The prostitute says “rip my stockings” and Murray thinks she’s saying “lip” or “lick.” The scene is so offensive it gives me a pit in my stomach. In other scenes Murray speaks to Japanese people with absolutely no consideration that they have no idea what he’s saying.

He acts out the stereotype of the Ugly American, and if I give Coppola the benefit of the doubt, she’s making a statement about how this is wrong. But I doubt many viewers get that message. Murray in particular displays such an awful sense of privilege and superiority that it’s hard to watch. He represents the worst of Americans that I’ve seen in Japan.

Johansson on the other hand does show some empathy and curiosity, something that Murray absolutely does not. She wanders into an Ikebana, or flower arranging, class in the hotel and is drawn in to creating a display.

One of the worst characters is the dumb American movie star Kelly who’s on a press tour of a martial arts B-movie, who is blissfully ignorant of her impact as a foreigner in a country she should respect.

Not surprisingly, Japanese food ends up being the target of ignorant Western perspectives too. After a shabu-shabu meal both Murray and Johannson’s character laugh about how awful it was that they have to cook their own food at the table.

Ultimately, the movie uses Japanese people, things, culture and everything in Tokyo as mere props–just an exotic, colorful and bewildering backdrop for these two characters’ tepid relationship. I’ll stick to my reliable stable of YouTubers living in Japan to share the energy and buzz of the country and its cities including Tokyo, without being lost in translation.

As cinematic art, it’s worth noting that this was one of the first realistic depictions of Tokyo in a Hollywood movie partly because it was done on location and much of it was done with available light and handheld cameras with a small budget and guerilla crew. That makes it an interesting movie to watch, but for me it’s not a great movie to pay attention to–the story irritates me.

It may be interesting to pull out the disc, if there’s still such a thing as a disc player, in another 20 years to see how the movie has aged by then.

And, aftrer writing this post, I remembered I had written about Hollywood films that showed Japan before, and found that piece, from 2017. I actually wrote about Lost in Translation back then and I pretty much had the same reaction that I expressed here. Take a look at “Japan through Hollywood’s lens over the decades“!

This post was originally edited and published in the Pacific Citizen newspaper.

© 2023 Gil Asakawa