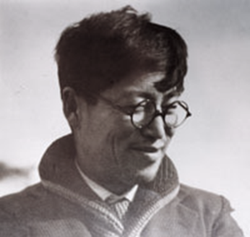

My grandfather, Wakaji Matsumoto, traveled across the Pacific Ocean to help his father in a foreign land, but he returned to his native Japan as an artist. He was a Japanese photographer who lived in two worlds—Los Angeles, California, and Hiroshima, Japan. His images captured the lives of Japanese immigrant farmers living in rural Los Angeles in the early 1900s, and also events and the everyday lives of people in Hiroshima.

While living in Los Angeles as a farmer, Wakaji studied photography and became an active member of a Japanese camera club in Los Angeles, and a pioneer in the Pictorialist movement. Wakaji returned with his family to his native Japan in 1927, pursuing his dream of becoming a professional photographer. He set up a photography studio, Hiroshima Shashinkan, in Hiroshima, where he worked as a freelance and newspaper photographer. Wakaji’s vast photographic collection represents rare images of urban and rural life in Hiroshima before the atomic bombing in 1945.

The Sojourn—Japanese Immigration to the United States

Wakaji’s father, Wakamatsu, was a farmer and fisherman from Hiroshima, Japan. Wakamatsu was the youngest in his family. His older brother inherited the family fortune, which is the custom in Japan. Wakamatsu didn’t think he could get ahead working for his brother, so in 1890, he and his wife Haru decided to go to Hawai‘i to work as contract laborers on the island of Kauai. They were among the nearly 30,000 workers sent by the Japanese government to Hawai‘i to work on sugar plantations, most of them from the Hiroshima area.

Wakaji and Matsu, their two oldest children, stayed behind with their grandparents in Hiroshima. After Wakamatsu completed his work contract, his wife and two children born in Hawai‘i went back to Japan, but Wakamatsu went to Los Angeles to become a farmer. He leased a hay ranch in Laguna (now a part of Los Angeles) where he also grew and sold fresh vegetables.

Wakaji’s Early Life in the US

In 1906, Wakamatsu sent for his son Wakaji to join him in the United States. Wakaji had no experience as a farmer, so he went to work in Los Angeles as a houseboy. He learned English there, and my grandmother told me that he would always reply “All right” when asked to do chores. His nickname was “Wakan” but he was known as “George” to his White employers who could not remember or pronounce his Japanese name. They would always say “Everything is all right for George!” After learning English during his stint as a houseboy, Wakaji went to work with his father on his produce farm.

Wakaji actually wanted to be a graphic designer but his father discouraged Wakaji from developing his artistic talents. Wakaji was not interested in farming and did not like working in the fields. He preferred delivering produce from the farm by horse team to the Los Angeles 7th Street Market.

After working for his father for several years, Wakaji was joined by his wife and my grandmother, Tei Kimura, a picture bride in 1912. Wakaji was a friend of Tei’s older brother, who helped arrange the long-distance marriage. Tei came from a samurai family in Wakaji’s hometown and did not know anything about farming.

Since Wakaji had no interest in farming, Wakamatsu taught Tei how to manage the farm and made her foreman and manager. Tei hired all the Japanese and Mexican laborers, supervised their work, and provided meals for the workers. She was a natural at it, and with the farm in good hands, Wakamatsu returned to Japan in 1917.

By 1927, Wakaji and Tei had eight children, Hiroshi (Roy) the oldest, then Takeshi, Tsutomu (Tom), Noboru, Harue, Isao, and Shizue—a brother Satoru died when he was 9 months old. My grandmother often said how it was hard work raising children, taking care of the farm, and feeding her family and all the workers! She told me how she learned Spanish, and even how to make tortillas for the Mexican workers!

After his father left for Japan, Wakaji was finally able to pursue what he really cared about. He kept up with farm work and deliveries, but also took a correspondence course in photography. He fell in love with photography and wanted to become a professional photographer. He took a course in San Diego at a photography school while Tei ran the farm and took care of the family. He later worked as an assistant at the Toyo Miyatake Studio in Little Tokyo. Miyatake was a well-known photographer at that time. My grandmother said it was Toyo’s family who baked biscuits for him the first time.

Wakaji became a skillful photographer while working with Miyatake and joined the Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California, a club based in Little Tokyo. He began to produce extraordinary panoramas of Japanese immigrant farms in the Los Angeles area and experimented with new Pictorialist art forms. According to my grandmother, it was during this time that he met prominent photographers of that period, including Edward Weston and Ansel Adams.

The Japanese Camera Pictorialists went on photographic field trips throughout the countryside and arranged exhibitions and catalogs of their work. The members of the club shared photographs and discussed what was happening in the art world, incorporating different styles into their work. Some of Wakaji’s work illustrates the concepts of soft focus and storytelling that popularized the Pictorialist movement of the early 20th century.

The Matsumoto farm was profitable in the 1920s but there were several years of crop failure due to bad weather. By 1923, due to pressure from White farmers, California strengthened alien land laws that prohibited Japanese from owning or sharecropping land, which was discouraging to Japanese farmers. At the same time, many Japanese American photographers had become active in the Los Angeles area. Financial challenges from farming and competition from other photographers were probably why Wakaji wanted to go back to Japan and open his own studio.

Becoming a professional photographer in Japan

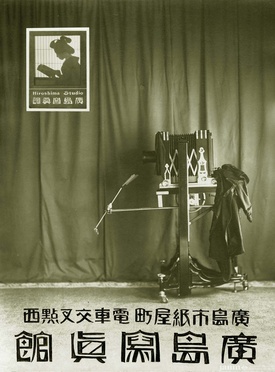

With earnings from the farm, Wakaji was able to buy the latest cameras and other photographic equipment to take back to Japan. He opened the Hiroshima Shashinkan (Hiroshima Photo Studio) at Sarugakucho in Hiroshima City (the present Kamiya-cho in the Naka Ward). Sogo Department Store now stands on that site and there is a small plaque marking the site of Wakaji’s Hiroshima Shashinkan.

Wakaji worked as a photographer at the Chugoku Newspaper Agency, getting his start by taking photos of roses and other floral themes. He used to say that flower arrangement helped him get new ideas for photography.

Wakaji sponsored the Hiroshima Koga Club, where photo enthusiasts got together and went on photography field trips. Wakaji was a skilled photographer and had the advantage of camera equipment not yet available in Japan. His work was highly regarded and his services were widely in demand.

Wakaji did studio work and commercial photography. He also worked for the Japanese military, taking photos of military dignitaries, activities, and events. He also took numerous photos of everyday life in Hiroshima City and the surrounding countryside. Many of the photographs taken during this period are the only record of people, events, and locations that were later destroyed by the atomic bomb.

By 1942, as the war progressed, photographic supplies were difficult to get, as chemicals and equipment went to the military. Wakaji had to close down his photography studio and move his family to the countryside. Loading a horse-drawn cart with all of his equipment, supplies, photographs, and family belongings, he and his family relocated to Jigozen, the small village where his parents lived, which was about ten miles from his photo studio in downtown Hiroshima.

Soon after, Wakaji was then drafted by the government to work as a laborer at a coal mine in Ube, Yamaguchi Prefecture. It was during this time that he developed a serious lung disease that lasted the rest of his life. My grandmother said that Wakaji got off from hard labor at the coal mine by giving away his portion of sake since he couldn’t drink. He also picked wild mushrooms in the forests of Ube and sold them for cigarettes!

Wakaji returned to Jigozen, located in an outlying area of Hiroshima, after working in the coal mines. He had a small studio darkroom in his home, but in March 1945, an American bomb was dropped during an air battle that destroyed Wakaji’s small studio and all of his remaining equipment and supplies. It was no longer possible for Wakaji to make a living through photography, but miraculously, his photographs and negatives survived intact.

Although living in the countryside about ten miles from the hypocenter of the atomic bomb, Wakaji and Tei both experienced the flash and shockwave of the bomb. My grandmother was hanging up her laundry to dry outside when the atomic bomb was dropped. She said it glittered up in the sky and started to spread toward them. Could that be a shock wave, the impact of explosion, or a hitodama (a fireball from Japanese folklore)? The bomb did not directly impact their village, and my grandparents ventured into Hiroshima through the wreckage to look for relatives among the survivors. They were able to find a cousin, who they wheeled out on a small cart to transport him back home, but he died along the way.

Wakaji and Tei’s experience during WWII also had another twist. Two of their sons, Hiroshi (Roy, my father, who was the eldest) and Tsutomu (Tom) were living in the United States when the war broke out, and both enlisted in the US military. Wakaji’s three other sons living in Japan were in the Japanese army—Takeshi at Kure Naval Base in Hiroshima, Noboru at Guadalcanal, and Isao in China.

My grandparents had no contact with their sons in America and did not know they were serving in the US military. My father, Roy, was a Nisei Japanese language interpreter for the Military Intelligence Service, fighting in Burma with the famed Merrill’s Marauders against the Japanese army. Luckily, he did not have to fight against his brothers in direct combat. All of Wakaji’s family survived the war, and were reunited during the Occupation period.

Life in Hiroshima was difficult after the bombing, with the devastation of the city and its infrastructure. With his small darkroom, photographic equipment, and supplies gone, Wakaji gave up photography as his livelihood.

I was ten years old when I met my grandfather while visiting Japan with my family several months before he passed away. Although I vaguely knew he was a photographer, I had no idea of the scope and artistic talent of his photographic skills. Suffering from poor health after working in the coal mines, my grandfather passed away in 1965, at seventy-six years of age. I wish I could have gotten to know him better.

In 2007, my cousin Hitoshi Ohuchi, the son of Wakaji’s youngest daughter, Shizue, discovered Wakaji’s photographs in a closet at the family home where he had put them for safekeeping since 1942. They were about to be thrown out as gomi (trash)—but luckily, Hitoshi, who is a photographer, recognized their value, and was able to save them. He informed the City of Hiroshima of their existence and donated the photographs to the Hiroshima City Archives where they are currently preserved and archived. Most of the photos of California and Japan had never been seen since before World War II.

Currently, several of Wakaji’s pre-war photographs of Hiroshima are featured in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. These photographs capture the essence of the events and the vibrant life in Hiroshima before the bomb. A wall-sized mural of Wakaji’s iconic 1938 photograph of Hiroshima at the “atomic dome” greets visitors when they first enter the museum. My hope is that my grandfather’s photographs will help bridge cultural understanding between the US and Japan, and help engage the public in understanding the important connections between historic and current social issues including immigration, racial and economic injustice, impacts of nuclear proliferation, and world peace.

*A note from the author: Most of what I know about my grandfather Wakaji I learned from my grandmother Tei, my own father, Roy Matsumoto, and Hitoshi, one of my Japanese cousins. I only met Wakaji once when I was ten years old, several months before he passed away. I remember him as a somewhat forbidding figure, so I am glad I also heard many stories about him from my grandmother. My cousin Hitoshi Ohuchi (Wakaji’s grandson) compiled a collection of oral history stories about the Matsumoto family which helps to fill in the picture.

* * * * *

This essay was written in conjunction with the Japanese American National Museum’s online exhibition, Wakaji Matsumoto—An Artist in Two Worlds: Los Angeles and Hiroshima, 1917–1944, which highlights Wakaji’s rare photographs of the Japanese American community in Los Angeles prior to World War II and urban life in Hiroshima prior to the 1945 atomic bombing of the city, and artistic photographs of daily life in both cities that were created as a form of personal expression.

View the online exhibition at janm.org/wakaji-matsumoto.

© 2022 Karen Matsumoto