If there was a sound that defined United States history, it would be jazz. As Amiri Baraka stated in his landmark book Blues People, jazz’s history is intertwined with the black experience from enslavement, emancipation, segregation, and eventually on to migration to cities. Rooted in the Blues and the African American gospel, and drawing from European classical music and other musical traditions, jazz emerged at the beginning of the 20th century as a cornerstone of American identity at home and abroad.

Within this larger history is the story of the Asian American musicians and fans who adopted jazz, both as part of assuming an American identity and as a form of protest against racial discrimination. These Japanese Americans helped popularize the genre, especially within the community, and it served to bring them together.

The late George Yoshida, a jazz musician and one-time incarceree at Poston, noted in his foundational book Reminiscing in Swingtime that Nisei participated in jazz groups dating as far back as the 1920s, and that jazz served as means of bringing disenchanted Nisei youth together during the incarceration. Yoshida identified a set of Nisei jazzmen, including Paul Higaki and Harry Kitano (who worked under the name Harry Lee).

More recently, Greg Robinson rediscovered the important Nisei jazz writer and publicist Ruth Sato Reinhardt, who operated the popular Chicago jazz club “Jazz Ltd.” and wrote for DownBeat magazine. One such individual who deserves attention is James Araki, the Nisei musician who popularized bebop in Japan during the occupation.

James Tomomasa Araki was born June 15, 1925 in Salt Lake City, Utah. During his childhood, Jimmie Araki moved with his family to several places in the West, and finally settled in Los Angeles in the late 1930s. His father, Hikotaro Araki, initially worked as a beekeeper in Montana, then and later found employment as a janitor for one of the motion picture studios in Hollywood.

During this time, Jimmie’s parents sent him to Japan for one year to learn Japanese. As a high school student, Jimmie Araki excelled academically at Hollywood High School. He helped form a Nisei social club called “The Mercuries” with several classmates, such as future Judge John Aiso’s Sansei son James, in October 1941, and served as its secretary-treasurer.

In April 1942, following the U.S. Army’s incarceration of Japanese Americans, Jim Araki and his family were sent to the Santa Anita Detention Center. During his months at Santa Anita, Araki took art classes and began to draw. His portrait of Hollywood star Irene Dunne was showcased at an art show at the Santa Anita camp alongside his sister Emily’s portrait of actor Charles Boyer. A few months later, the Army transferred the Araki family to the Gila River concentration camp in Arizona.

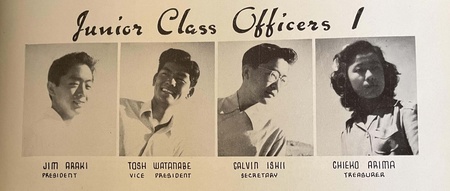

At Gila, Jimmie Araki continued his studies at the Butte camp high school. He was elected Junior Class president in 1943, and worked on the art team for the school’s yearbook Year’s Flight. On February 3rd, 1944, the Gila News-Courier announced that Jimmie Araki and six other students had graduated from Butte camp high school. It was during high school that Araki began to study music; he acquired a “cheap clarinet” while in camp, and played in the school’s swing band the Music Makers.

Jimmie Araki’s time at Gila River came to an end in June 1944, when he received news from the War Department that he had been drafted. He enlisted in the Army’s Military Intelligence Service, and was sent to the MIS school at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Thanks to his fluency in Japanese, Araki rose through the ranks, and a year later became an instructor of Japanese at Fort Snelling. At the same time, Araki continued to play music with the school’s swing band, the “Eager Beavers,” and started his own combo. As George Yoshida (who also played alongside Araki in the Eager Beavers) described in Reminiscing in Swingtime, Araki possessed enormous talent as a musician; he taught himself saxophone, piano, trumpet, and guitar, and was often found by fellow bandmates practicing piano studiously alone on the Fort Snelling stage, memorizing chord changes.

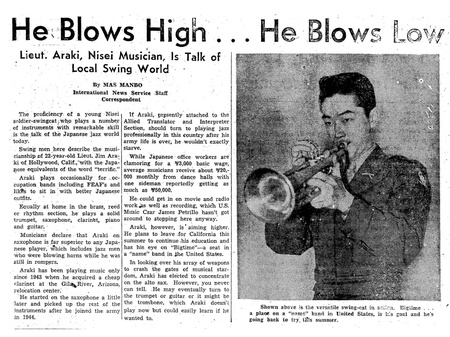

In 1946, the Army sent Araki to Japan to serve in the Occupation. Promoted to the rank of lieutenant, Araki worked as a translator for the Allied Translator and Interpreter Section of General Headquarters in Tokyo. As a jazz musician, Araki arrived at the right time in Japan; after years of government bans of jazz, Japanese listeners actively sought out jazz music in the postwar scene. Historian E. Taylor Atkins cites Araki and jazz pianist Hampton Hawes as the two Army GIs who popularized jazz in postwar Japan. In his book Blue Nippon, Atkins argues that several recording sessions of Araki’s compositions in August 1947 brought about the first ‘modern jazz’ recordings in Japan, all produced by an all-star band named the Victor Hot Club. Araki then organized the band into a ‘bebop study group’ that performed Araki’s arrangements in various clubs across Tokyo.

By 1948, the 22-year-old Araki found himself at the top of the Tokyo jazz scene. Nisei journalist Mas Manbo profiled Araki in an article for The Nippon Times, dubbing Araki a “soldier-swingcat,” and added that most Japanese musicians described Araki as “far superior.” The Rafu Shimpo in February 1948 noted that jukeboxes across Japan featured several of Araki’s singles, such as “A.P. 500” and “Night in Pakistan.” The rise to stardom shocked Araki; he later confessed that “I wrote eight tunes just for the fun of it,” gave them to friends, and soon thereafter the Victor Company of Japan pressed them into an “Araki album.” Musicians in Japan described his talents as “godlike,” and thus bestowed upon Araki the moniker of kamisama.

In 1949, Araki left the Army and returned to Los Angeles. He then joined a new swing group, Tetsu Bessho and his “Nisei Serenaders,” as their pianist. Within a year, Araki became head of the group and changed the name to “James Araki and his Nisei Serenaders.” Araki also performed alongside Tak Shindo - the famed Nisei musician and composer of several Hollywood film (Sayonara) and television themes (Gunsmoke, The Ed Sullivan Show) - at several community events.

In April 1951, Araki invited Nisei singer and actor Lane Nakano to regularly perform along with the Serenaders. The group continued to perform until 1954. He then began playing in a new combo, the Miyako Trio, with Paul Togawa.

In 1955, Araki’s talents were recognized by famed band leader Lionel Hampton, who invited Araki to record with his group. Araki cut several records with Hampton’s group, including “Lionel Hampton’s Big Band,” “Hamp,” and “Lionel Hampton and his Orchestra,” each one of which credited Araki as a saxophonist or pianist. It is also likely that the single “G.H.Q.”, listed on one of the albums, was written by Araki, given that the single’s name draws from General Headquarters in Tokyo, where Araki served during the Occupation. On Hampton’s 1955 single “Midnight Sun,” Araki played alto saxophone alongside famed drummer Buddy Rich.

In 1959, Jimmie Araki returned to Japan to record his last studio album. Titled Jazz Beat, the album featured original compositions and arrangements by Araki as performed by Araki on piano and sax, Mitsuru Ono on bass, and George Kawaguchi on drums. The recording was dubbed the “Midnight sessions” due to the performance being recorded at midnight on June 10, 1959, and was released by Victor in Japan.

“Take the A Train” by Jimmy Araki

Although most of Araki’s early adult life was defined by his musical career, he soon changed his trajectory. After briefly studying music at the University of California, Los Angeles, Araki decided that studying music was “too familiar” and decided to study Japanese literature. He proceeded to earn his Ph.D in Japanese literature at UCLA and became a professor of Japanese Literature at University of Hawaii in 1964. Over the course of his academic career, Araki translated several classical Japanese texts into English.

Yet despite his career change, Araki continued to play and write about music. In November 1979, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin reported that Araki took the stage with ukulele virtuoso Herb Ohta (aka “Ohta-san”) to demonstrate his saxophone skills. A few months later, in February 1980, The Star-Bulletin offered Araki a chance to cover the jazz scene in Hawaii. Araki’s article, which appeared on February 24, 1980, profiled several jazz clubs on Oahu, and noted several rising musicians, including Ohta-san. Although the editor promised readers that Araki would continue to review the jazz clubs of Hawaii, the February 24th article would be his only review. In later years, Araki focused more on his academic work as chair of the University of Hawaii’s East Asian Languages and Literature Department.

In 1991, Araki returned to California for health reasons. In November 1991, the Japanese government awarded Araki the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays and Rosettes for his popularization of jazz in postwar Japan and his translation work. The award ceremony would be one of Araki’s last public appearances. He succumbed to cancer and died on December 22, 1991, at 66 years old.

James Araki’s music career demonstrates that Japanese Americans musicians played an important part in defining jazz and popularizing it abroad. In contrast to the later Cold War jazz tours in Europe and the Middle East, Araki’s work in Japan illustrates the grassroots movement through which jazz became popularized in Japan, as well as the rich experiences of many Nisei living there in the postwar era.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen