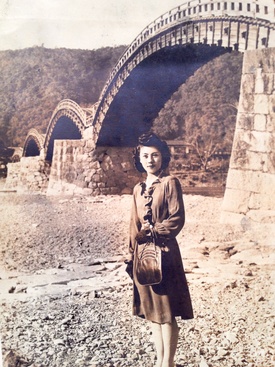

During World War II, my Nisei mother and her family were sent from Honolulu to a concentration camp in Arkansas, and from there they were deported to Japan, where they lived in Iwakuni. In the first photo, taken in the late 1940s, my mom is on the very left, with a young girl in her lap, and you can see Iwakuni’s famous Kintaikyo in the distance.

My mother had such a deep attachment to the centuries-old bridge, which stood gracefully spanning the Nishiki River even as the rest of Japan was being ravaged by war. Ironically, the Kintaikyo survived WWII only to be destroyed in 1950 by flooding from a typhoon. But it was reconstructed a few years later based on the original design, only this time using metal nails.

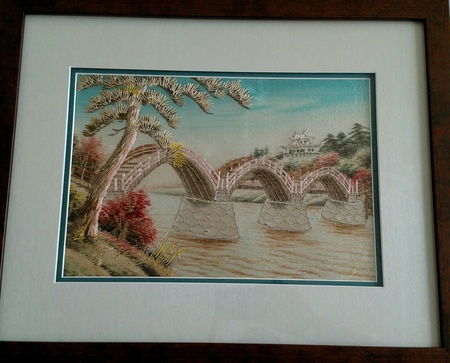

My mother did not get to see the Kintaikyo being rebuilt because, after marrying my father, she moved back to Honolulu in the early 1950s. In their bedroom, though, she always displayed a silk tapestry of the bridge, which her father had given her as a going-away present.

Unfortunately, my photo of that tapestry is recent and doesn’t adequately capture its original vivid colors, which have faded over the years from the brilliant Hawaiian sunshine. But when I was a kid, my mom would point to the tapestry and say, “That’s where my family is from. One day I’ll take you there and you can meet your grandparents and all my sisters and brothers.”

When I was ten, our family did travel to Japan and I got to meet my mother’s parents and her siblings, and I crossed the Kintaikyo. In the right photo (taken in 1969), I’m the short kid immediately to my mom’s right, and my Uncle Yuki, whom I had just met for the first time, is just to my right.

My grandfather's house was a short walk to the bridge, and we stayed with him for two wonderful weeks. I have such fond memories of that idyllic summer. It was like being in a Japanese fairytale – the Kintaikyo with its five elegant wooden arches, the winding Nishiki River, majestic Iwakuni Castle perched in the hills above. I especially remember my Uncle Yuki taking us cormorant fishing at night on a long, slender wooden boat, with a fire torch to guide us.

He also taught me how to play mah-jongg, a game that immediately captivated my interest with its different tiles for red, green, and white dragons; the four seasons; and the east, west, north, and south winds. And he’d sneak me into pachinko parlors, where we’d spend hours, my senses filled with the blinking lights of the machines, the whirling cacophony of sounds, and the metallic smell of those tiny chrome-plated balls. These were the days when the machines were completely manual, so you’d have to use your index finger to flick a slender, curved lever, flinging the balls ricocheting through a field of pins. Uncle Yuki taught me how to apply just the right pressure to get the balls to go into the center basket to score the biggest jackpot, which would then release a cascade of those metal balls noisily tumbling down into a receptacle at the machine’s bottom.

From that magical, memorable summer, fifty years would pass before I would cross the Kintaikyo again, and this time I did so with my husband. My mother had died several years earlier, and I got emotional climbing those wooden steps, thinking about the times she had ascended those very steps as a young woman who had been incarcerated by her own country and then deported to a foreign land that she had never been to. After the atomic bombing of nearby Hiroshima, did the sight of the Kintaikyo during spring when the cherry blossoms were in full bloom allow some hope to my mother, if not a brief escape from the daily hardships of life as Japan struggled to rebuild itself?

On that trip in 2019, I also got to visit my Uncle Yuki for the last time. He was 88 and residing in an assisted-living facility, dementia having engulfed his mind. He didn’t recognize me but I was touched to see him all the same, although I was upset to learn that, in his diminished state, he would often mutter things in English, which the staff couldn’t understand. My uncle would pass away a year and a half later, and his death filled me with a quiet, deep grief. He had been the last survivor of my mother’s nine siblings (six brothers and three sisters) but it wasn’t just the final passing of my family’s Nisei generation that had rendered me so disconsolate.

I had always felt a deep bond with my Uncle Yuki, even though we had lived thousands of miles apart. My mother once told me this about her youngest brother: “You two are actually very similar, both so shy and introverted as kids who turned to books for comfort and company.” Uncle Yuki and I were kindred spirits who should have been closer had WWII not wrenched my mother’s family from its nascent roots in Hawaii. So from my uncle’s death I also grieved for a relationship that never was.

As I now begin to enter my elderly years, I’ve come to understand that the Kintaikyo was so much more than just a bridge to my mother. For her, I believe it was an iconic symbol of beauty amidst devastation, resilience won from hardship, joy gleaned from sadness. And the elegant, magnificent bridge, first built in the 1600s, was also a source of intense pride for my mother. She had suffered such ugly discrimination during the war, and she didn’t want to pass that painful baggage on to her children. She wanted us to always be proud of our Japanese heritage, even as my brothers and I became increasingly Americanized over the years.

For me, the Kintaikyo is a bridge to my past, a link to the woman my mother was, and a tether to our family’s rich history. Even though I now live in Boston, halfway around the world from Japan, this exquisite wooden bridge in Iwakuni holds such nostalgic power. Every time I see a photo of it, a wave of natsukashii washes over me. When I’ve tried to describe what natsukashii is to someone who doesn’t know the Japanese word, I always have such trouble. The best I can do is to say it’s a nostalgic yearning that can be melancholic while also being reflective and appreciative of the memories one has. I’ve been told that the closest word to it is saudade in Portuguese, yet I can't think of a word in English that captures such a complex feeling, that indescribable mix of emotions. But here I’ve written more than one thousand words that I hope conveys some sense of one Sansei’s feelings of natsukashii for the faraway land of his ancestors.

© 2022 Alden M. Hayashi