That Saturday, when I arrived at my parents’ house to pick up Dad, he was already sitting outside, waiting for me with two large paper bags.

“Sorry, am I late?” I asked.

“Look at what I picked this morning,” he said, pointing to the two bags. Inside were white Piri mangoes from his tree as well as several jabong, a type of grapefruit with the sweetness of oranges.

“Wow, Tanaka-san is gonna love these!”

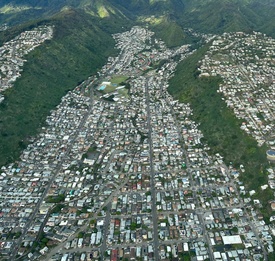

I didn’t tell Dad that, actually, I had allowed some extra time in our schedule to stop at Liliha Bakery to buy some cocoa cream puffs, just so that we wouldn’t arrive at Tanaka-san’s house empty handed. But since Dad had already taken care of that, I figured we could take a leisurely drive through the city, avoiding the highway, to get to where Tanaka-san lived in Palolo Valley.

It was a beautiful, warm day in Honolulu, with just a few white clouds hanging low in the brilliant, blue sky beyond Diamond Head. As we winded through the streets of Liliha, Punchbowl, McCully, and Kaimuki, Dad and I sat in silence, but it was a familiar, comfortable feeling, unlike the unease I had often experienced when I was a young kid.

Back then, Dad and I had difficulty talking to each other, and I’d dread Sundays when we would take long drives to the North Shore to visit his cousin in Waialua. Mom, who usually acted as our buffer in those days, would do her grocery shopping then, so it was just Dad and me, and we’d sit in awkward silence, barely saying a few words to each other as we drove from Honolulu past Waipio and along the massive pineapple fields that eventually gave way to a breathtaking view of the ocean along the northern coast of Oahu. During those days, when I was in elementary school, I was interested in only two things: collecting coins and building models of battleships. Meanwhile my father was mainly focused on gardening, fishing, and his beloved Dodgers. It seemed like we had no common ground, no neutral territory for us to communicate.

The distance I felt from him only increased when I got older, as earlier inklings I had of being different coalesced into the growing realization that I was gay. Then, after I had officially come out during my junior year at the University of Hawaii, this only further alienated me from my father, leaving us with little to talk about beyond the weather. But things eventually began to change when, after I had graduated from college, James and I started seeing each other. We dated for several years before moving in together, and we’ve remained a couple ever since.

Over the many years of our relationship, Dad slowly, even begrudgingly at first, began to realize the strength of James’s and my bond, that we loved, supported, and would take care of each other through all the hardships and joys of life. On some level, my father must have been comforted knowing that he didn’t need to worry about my well-being after he and Mom passed, because James would always be there for me.

My parents had seen so many marriages of their nephews, nieces, and friends’ children fall apart, some after only a few years, whereas James and I had steadfastly weathered three decades together, and our enduring relationship eventually helped Dad make peace with my being gay. That acceptance, I felt, was my father’s expression of his paternal love. It was a hard-fought battle that eventually allowed me to savor a sweet victory.

I now took pleasure in every single instance of Dad’s thoughtful gestures toward my long-time partner — his asking, for example, whether James might appreciate a used poker table. And I was grateful that Dad and I could now enjoy long car rides with each other, sitting in an easy, comfortable silence that had eluded us so many years ago.

As we neared Tanaka-san’s home, heading down his dead-end street, I tried to remember the last time that I was actually there. It might have been a birthday party for his daughter Lynne, who was a year younger than me. We were probably only in second or third grade then, so that would have been more than forty years ago.

From what I could remember, the house seemed to be basically the same, except at some point Tanaka-san must have chopped down the large lychee tree in the front yard. Also, there was now a wooden ramp that wrapped in front of the one-story plantation-style structure, dramatically altering the aesthetics of what used to be a beautiful front lanai.

“Did you know that Tanaka-san built the ramp for his wife by himself?” Dad told me. “This was when she became too ill and had to use a wheelchair.”

“When did she pass, was it recently?”

“Maybe just three or four years ago.”

After parking my car in the short driveway, we made our way to the front of Tanaka-san’s house, where Dad elected to use the handicap ramp even though he was quite capable of handling the short flight of steps to the entrance. I joined him, admiring Tanaka-san’s skilled carpentry. We knocked on the front door and were greeted by Lynne, or at least I assumed it was Lynne.

“I hope you remember me,” I told her.

“Oh my gosh, how many years has it been?”

Lynne smiled and thanked us for the fresh fruit, but she seemed somewhat withdrawn, a bit sullen even. This was nothing like the child I remembered from elementary school. She was a cute and lively girl then, her long pigtails always bouncing in the air as she ran around the house.

When we entered the living room, Tanaka-san got up from his recliner and, somewhat warily, greeted Dad before quickly turning toward me. “Long time no see! When was the last time you were here?”

“Geesh,” I shook my head, “I don’t even know. Probably when Lynne and I were young kids.”

“Oh, then you have to see the family room. I added all this shelving.”

Tanaka-san took me to the adjoining room, where one long wall accommodated rows of built-in stained maple-wood shelves displaying not only books but an impressive collection of kokeshi dolls, assorted tchotchkes, and dozens of framed photos. In one of those photographs, a young Lynne, the girl I remembered, smiled with a missing front tooth. The largest photo was a black-and-white of Tanaka-san and his wife on their wedding day, she in a splendid kimono and he in a classy white tux. As I admired the photograph, he said, “She was beautiful, huh.”

“Yes, so elegant, regal like.”

“Did you know your father wanted her? But I got her first, not him.”

Just then Dad poked his head into the family room. “Come on, I’m really hungry,” he said. “Let’s get lunch.”

Tanaka-san then rushed to his bedroom to grab a light jacket, while Dad whispered to me, “What was he telling you about his wife?”

“Oh nothing,” I shook my head.

“Yep, abudachi all right.”

Outside, I helped Tanaka-san into the back seat of my SUV, while Dad settled himself in the front passenger side. With the two men secured with seat belts, I reversed out of the drive and started down the road when I heard a muffled tapping from the rear of the car. Damn, I thought to myself as I checked the dashboard, but thankfully none of the warning signals—oil pressure, engine check, temperature warning—indicated any problem. As I continued driving, though, the sound became a louder rapping noise, so I pulled over.

Now the tapping was on my side window and I looked to see Lynne. When I rolled down my window, thinking maybe my wallet might have fallen out of my jeans on the driveway, she said, “Hey, remember me? Is it okay if I join you?”

“Sure,” I muttered, as I unlocked the back door, confused as to why she’d want to have lunch with us. If anything, I figured that she’d relish having some free time to herself. But then the thought crossed my mind: maybe she didn’t trust me with her father. This annoyed me—after all, I was more than capable of taking care of two elderly men for an afternoon—but I brushed that feeling aside, convincing myself to just make the best of the situation.

At Zippy’s, we were escorted to a booth, with Dad sitting across the table from Tanaka-san, and me opposite Lynne. That’s just great, I thought to myself. Now I had to make small talk with a virtual stranger while Dad caught up with his longtime friend. But, while Lynne told me about her recent divorce and about her having to take a leave of absence from her job to take care of her father, whose health had been on the decline, I was also half-listening to the conversation right next to us.

For the first few minutes, Dad and Tanaka-san started off tentatively, unsure where to pick up on their decades-long friendship. Slowly, though, they began talking about their old poker gang, and soon enough they were chatting just like old times, exchanging gossip and reminiscing about their past exploits. They were even teasing each other, playfully boasting about who was the faster swimmer, the more skilled bowler, and then better fisherman. I breathed a sigh of relief to myself and tried to concentrate on my own conversation with Lynne.

*“The Poker Table” was originally published in The Gordon Square Review (issue 12).

© 2023 Alden M. Hayashi