Kinship Ties Forged and Broken

Back at Manzanar, Kenji and his siblings eventually learned that his father was imprisoned in the same concentration camp as them. Although the family was not immediately allowed to live together again, they were permitted to visit one another. His mother, who had been exposed to shock therapy during her stay at the sanatorium, eventually joined the family as well.

But Kenji says the family was broken due to the long separation during a critical period of the children’s development. When they could finally live together again, he says they didn’t even feel like a family any more. “We were just five bodies in a room,” he said.1

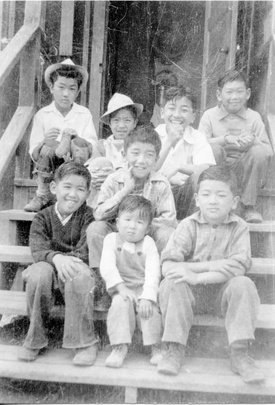

Meanwhile, those who remained at the Children’s Village formed new kinds of kinship amongst themselves. Several survivors recalled John Sohei Hohri as being a particularly strong pillar of that Children’s Village family. Hohri was himself an orphan, first at the Shonien and later at the Children’s Village until he turned 18 and was “released” to the larger concentration camp. He returned to the orphanage for the duration of his time at Manzanar as a staff member, but also so much more. Many identified him as an older brother figure who captivated the children through nightly story time sessions in which he would recount from memory captivating versions of Homer’s Odyssey and Les Miserables.2

As the WRA moved to shutter Manzanar in 1945, the orphaned children who remained were once again subjected to separation, this time from the strong kinship networks they had formed with staff and fellow orphans. Many reported that this move was even more painful than the others because they were losing the only family they had ever known.

Since the Japanese orphanages would not be reopening, the residents were left to seek other placement options. In some cases this meant reunification with parents; while for some it meant going wherever they could find jobs as in-home domestic workers. Others still were adopted or placed in non-Japanese foster homes.3

Wilma Stuart, a white woman who lived in Los Angeles, hosted two girls after they were released from the Children’s Village. In an oral history conducted in 1993, it was clear that she cared for the girls but was oblivious to the lingering trauma or ongoing discrimination they were surely grappling with.4

“I don’t know about Manzanar,” she told an interviewer. “They were passing out the children to homes when the war was over. I asked them if they had any they could send me, so they sent me over the two, Annie and Celeste. Celeste stayed with me for a long time. Annie stayed the longest.”

Despite the breakup of the family systems that had formed within the Children’s Village, many of the former residents remained connected to each other for the rest of their lives. In a talk at the 1992 Manzanar Children’s Village Reunion in Los Angeles, Sohei Hohri recalled the strong sense of camaraderie that still existed among the former residents of the orphanage: “Three years ago Shioo Matsuno said it best with these words to Aki Isozaki and me: ‘You are my brothers.’ The passing years have proven it, and our hearts say it is so: Sisters and brothers.”5

But Hohri, who had gone on to become an artist, librarian, and avid book collector, also noted that, “in all of America’s shameful, illegal internment of Japanese and Japanese Americans, the most shameful episode remains the internment of orphanage children. Taken not only from orphanages, but even from foster homes.”

Indeed, the Children’s Village and the decisions about who should be detained within its walls, made an even greater farce out of the idea that an entire race of people, many of them born on American soil, were harboring some allegiance to a foreign power. While the entire incarceration was premised upon unfounded racist paranoia, the act of incarcerating children—some of whom had only nominal ties to Japanese American identity—casts an even brighter light on the hypocrisy that undergirded the decision to imprison an entire population based on their race and ancestral origins.

Seeing the treatment of Japanese American orphans within this larger trajectory of family separation underscores a particular pattern of US settler colonialism: one in which kinship networks were disrupted and replaced with paternalistic attempts to mold a compliant citizenry.

Family Separation Today

Japanese American activists fought for and won reparations for this injustice in the 1980s. A presidential apology and payouts of $20,000 to living survivors of WWII incarceration is far from an adequate amends considering the the human and financial tolls of the incarceration, and yet it’s still noteworthy considering that African Americans and Native Americans have yet to receive any kind of similar reparations for the centuries of atrocities they have endured. This disparity is partly what motivates ongoing social justice action among Japanese American survivors and descendents today.

The grassroots coalition Tsuru for Solidarity formed in response to the Trump administration’s blatantly inhumane policy of separating immigrant families in an attempt to quell border crossing. Tsuru for Solidarity’s first action took place at the biannual Tule Lake pilgrimage, which in 2018 happened to coincide with nationwide Families Belong Together actions organized by Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal.

One octogenarian who himself had been incarcerated as a child said he had never identified as an activist and was initially reluctant to join the protest, but during the action, was out there with dozens of others pumping his fist in the air and yelling “Kodomo no tame ni (for the sake of the children) / they’re our children, set them free.”

Survivors, descendants, and allies also planned a protest at the largest prison for immigrant families, the Dilley detention facility outside of San Antonio, Texas, just miles from where Japanese American and Japanese Latin American families had been detained at the Crystal City internment camp. The group has since orgranized to protest the detention of undocumented immigrants at sites all over the country.

Some of these actions have taken place at sites of multilayered violence. Fort Sill in Oklahoma, for example, was proposed as a prison for undocumented children separated from their parents at the border. Previously, the facility had been used as a prison for Japanese Americans during WWII, and as a Native American boarding school, and as a Prisoner of War camp for members of the Chiricahua Apache including Geronimo, who is now laid to rest there.6

When members of Tsuru for Solidarity gathered to protest at Fort Sill in 2018 a guard tried to force them to move. In Democracy Now footage of the event, Satsuki Ina, a WWII incarceration survivor and one of the founders of Tsuru for Solidarity, can be seen holding her ground and stating firmly, “We’ve been removed too many times.”7

In considering the histories and ongoing traumas of family separation and child incarceration, Satsuki’s act of refusal and the larger solidarity movement she’s part of, remind us that another world is possible. Family separation is part of our past, it’s part of our present, but we can collectively work to make sure it’s no one’s future.

Notes:

1. Suematsu, Ibid.

2. Nobe, 70.

3. Nobe, Ibid.

4. Stuart, “Interview.”

5. John Sohei Hohri, Manzanar Children’s Village Reunion Talk, May 24 1992, (accessed online Sept 21 2021)

6. Nina Wallace and Natasha Varner, “Fort Sill is a Site of Ongoing Trauma,” Densho Blog, June 12, 2019.

7. “Japanese-American Internment Survivors Protest Plan to Jail Migrant Kids At Fort Sill, a WWII Camp,” Democracy Now, June 24, 2019, accessed Oct. 18 2021.

Bibliography

Hohri, John Sohei. Manzanar Children’s Village Reunion Talk, May 24 1992, (accessed online Sept 21 2021)

Irwin, Catherine. “Manzanar Children’s Village,” Densho Encyclopedia (accessed Oct 12 2021).

“Japanese-American Internment Survivors Protest Plan to Jail Migrant Kids At Fort Sill,” a WWII Camp,” Democracy Now, June 24, 2019 (accessed online Oct 18 2021)

Maruyama, Hana, “What Remains: Japanese American World War II Incarceration in Relation to American Indian Dispossession.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota, 2021.

Nobe, Lisa. “The Children’s Village at Manzanar: The World War II Eviction and Detention of Japanese American Orphans.” Journal of the West 38, no. 2 (1999): 65-71.

Stuart, Wilma. “Interview with Wilma Stuart.” By Noemi Romero and Celia Cardenas. Children’s Village at Manzanar Oral History Project, July 11, 1993 (accessed online Oct 12 2021)

Suematsu, Kenji. “Interview with Kenji Suematsu.” By Sharon Yamato. Densho Visual History Collection, April 19, 2012 (accessed online Sept 21 2021)

Tawa, Renee. “Childhood Lost: the Orphans of Manzanar.” The Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, CA, March 11, 1997 (accessed online Sept 21 2021)

Wallace, Nina and Natasha Varner, “Fort Sill is a Site of Ongoing Trauma,” Densho Blog, June 12, 2019 (accessed online Oct 12 2021)

*This post was originally cross-published by Densho and Tropics of Meta: Historiography for the Masses.

© 2021 Natasha Varner