When asked to review Yamato Colony: The Pioneers Who Brought Japan to Florida for the Discover Nikkei site, I was delighted to oblige for two main reasons. The first was my passionate interest as a historian in Japanese American communities outside of those well-known and amply documented ones on the West Coast. This interest was catalyzed by my participation in the Japanese American National Museum (JANM)-sponsored REgenerations Oral History Project (1997-2000), which encompassed World War II and postwar Nikkei resettlement in midwestern Chicago (as well as three California cities). A few years later, my interest was fanned into flames by my involvement in another JANM-spearheaded endeavor, the Enduring Communities Project (2004-2008). While primarily focusing attention on the Japanese American historical experience in the states of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah, this project also embraced the parallel development of Nikkei communities in nine other states within the nation’s so-called Interior West region.

The second reason for my receptivity to reviewing the Yamato Colony volume was related to the state of Florida, which for some thirty-five years my wife and I traveled to quite frequently to visit my late brother Roy, a University of South Florida sociologist, and his family at their Tampa home. I must admit, however, that not until I encountered the Japanese writer Ryuske Kawai’s remarkable book here under review did I have any sense whatsoever of a Nikkei community presence in, of all places, the Sunshine State. So, I welcomed the chance, albeit very belatedly, to be enlightened on this subject.

Yamato Colony’s core story is the 1905 creation and subsequent development of an agricultural village (mura) of Japanese-ancestry settlers in southern Florida, a state which in 1900 counted only one Nikkei resident. This effort at foreign settlement occurred at a time when Japan’s government was simultaneously seeking to reduce its burgeoning population and enhance its imperialistic ambitions to gain productive colonies outside of the US West Coast, where anti-Japanese sentiment and actions were then steeply escalating. Spearheaded by Issei Jo Sakai, an enterprising recent graduate of New York University’s School of Commerce, Finance and Accounting, Yamato Colony’s originating population of Yamato Colony was fortified by a cadre of considerably less than the anticipated forty male migrants from Japan. Most of these pioneers were prominent in their home communities, possessed of some material well-being, English-speaking, intelligent (some were intellectuals), educated, refined, and hardworking. However, all but two were utterly bereft of agricultural experience.

Notwithstanding the settlers’ general unfamiliarity with the procedures and demands of farming and the early defection of some founders because of their disgruntlement with Sakai’s leadership style, once the men, in July 1905, acquired a 1,100-acre tract of land in the small community of Wyman (located between Boca Raton and Delray Beach) to situate the Yamato Colony, they achieved progressive communal success. In so doing, however, they had to overcome the formidable hazards of a subtropical climate, high temperatures, torrential rainfall, enervating humidity, swarming mosquito and gnat attacks, flooding swampland, typhoid fever, poisonous snakes and alligators, and armed robbers. Fortunately, the colonists were hard-working, resourceful, and blessed with benign and supportive neighbors, their own general store, a supply and services center in Delray Beach, a post office in Wyman, proximity to a new train station and a nearby packinghouse, fertile soil, and an ample water supply.

By 1908, the Yamato Colony swelled to 40 people, including the first female colonist, Jo Sakai’s wife, Sada, who over the next few years gave birth to five daughters, while at the same time performed a leadership role among the other women colonists who followed in her wake. By 1908 as well, many of the colonists moved from renting land to owning it, often of five acres or more. The expectation was that annually they would be collectively shipping twenty thousand crates of tomatoes and bringing in earnings of over forty thousand dollars. Within that same year, they produced a flourishing pineapple crop, which was trained away in iced freight cars from the site for ultimate export to England. In addition, they added many other vegetable crops—eggplants, peppers, green beans, lima beans, and squash—to be marketed with their tomatoes in Northeastern, Midwestern, and West Coast cities. In their farming operations, colonists employed both white and black workers (the former mostly packed while the latter mostly picked). For their own consumption, colonists shot wild game birds, grew fruit trees, and caught fresh ocean fish on Florida’s Atlantic coast. Their diet blended Japanese dishes and American ones.

Social, cultural, and educational activities complemented the colonists’ economic pursuits. Holidays, especially New Year’s Day and Christmas, were roundly celebrated; picnics, often held on the beach, were common occurrences in the interval after harvest and before planting; and the burgeoning number of Nikkei children attended school with area white students in the colony’s one-room schoolhouse.

It is difficult to discern from Kawai’s narrative, precisely for how long the state of affairs sketched above endured, but it appears that it was prolonged to a lesser or greater extent through the 1920s, declined in the 1930s, and had virtually ended with the onset of World War II, when the 5,820-acre tract of land encompassing the Yamato Colony was confiscated by the US government and made into an Army Air Corps technical training base.

The second part of Yamato Colony shifts from the life and collapse of the colony to its legacy as vividly represented through the life experiences of its longest surviving early settler, Sukeji Morikami, who died in 1976. The short version is this: following a long life as a bachelor agriculturalist, Morikami amassed a considerable wealth in land, which he eventually donated to Palm Beach County for the purpose of becoming a park. Within this park was constructed a magnificent house, which was modeled after an imperial villa in Kyoto and elegantly situated on an island within a serene pond. This house in Morikami Park became a museum to exhibit, among many other things, photographs relating the history of the Yamato Colony. In 2005, a celebration commemorating the centennial of the Yamato Colony was held at Morikami Park. Fittingly, this fete was attended by some fifty descendants of former colony settlers and their families.

Although I wish that a map depicting the settlement’s geographical location in Florida could have been included in Yamato Colony, as well as more solid dating rendered for the chronological evolution of the colony, these matters are of little consequence as against the manifold achievements that its author has fashioned: a captivating historical treatment of an overlooked chapter in Japanese American history; a narrative that is engaging, informative, and rooted in both historical research and creative vision; and a book that is accessible and inviting to a universal readership.

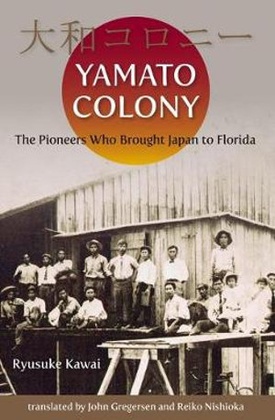

YAMATO COLONY: THE PIONEERS WHO BROUGHT JAPAN TO FLORIDA

By Ryuske Kawai

(Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2020, 189 pp., $19.95 paperback)

Editor’s note: This book received the 2021 Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Award for the best book on ethnic groups or social issues from the Florida Historical Society.

© 2020 Arthur A. Hansen