On April 28, 1908, the first group of Japanese immigrants to Brazil, the immigrant ship "Kasato Maru," left Kobe Port with 781 people on board, and arrived in Santos on June 18. This year marks the 111th year since then. Through many twists and turns, Brazil has today become the world's largest Japanese community, numbering approximately 1.9 million people. On July 8, a special ceremony was held at the Federal Senate to mark the 111th anniversary of Japanese immigration to Brazil, celebrating the achievements of these pioneering Japanese immigrants to Brazil.

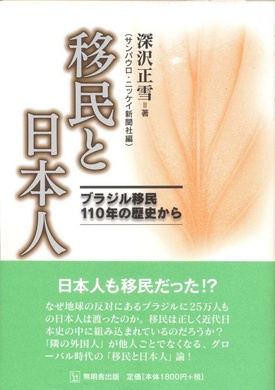

On this turning point of the 111th anniversary, "Immigrants and the Japanese: From the 110-year history of immigration to Brazil" (Mumeisha Publishing) was published by Masayuki Fukazawa, editor in chief of the Nikkei Shimbun newspaper in Sao Paulo (edited by Nikkei Shimbun). This book is extremely interesting and sets itself apart from previous studies of Japanese immigration to "Brazil" in that the author reexamines the history of immigration, which is the "B-side" of Japanese history, and attempts to incorporate the history of Japanese immigration to Brazil into the history of modern Japan.

Drawing on his many years of experience and insight as a journalist, he has pored over a vast amount of material on both Japan and Brazil, and has energetically published books such as If a Single Grain of Rice Does Not Die: 100 Years of Japanese Immigrants Settling in the Registro Region of Brazil (Mumeisha Publishing, 2014) and The Untold Tales of the Winners: 70 Years of Japanese Immigrants to Brazil After the War (same publisher, 2017).In this book, he questions "why and what kind of Japanese left Japan" and, in other words, the "roots" of Japanese immigrants.

In response to these questions, the author divides the roots of Japanese immigrants to Brazil into the "source" (chapter 1) and the "main stream" (chapter 2 onwards), much like the Amazon River, and further divides the latter into "(hidden) undercurrents" and "sidestreams". When did Japanese people first appear in South America? Also, "why" and "how" did they come to South America? In "the source", he traces these questions back to the Azuchi-Momoyama period, highlighting their connection to Christianity, such as the existence of hidden Christians and Christian daimyo at the time, and Toyotomi Hideyoshi's edict to expel the missionaries.

The "main stream" from the second chapter to the final chapter mainly tackles a new theme related to Japanese immigration to Brazil after the Meiji era, but with a different flavor from the conventional themes. As the author mentions many times, the reason why Japanese immigrants went to Brazil was due to the social situation in Japan at the time, which was a deadlock, with population growth and the accompanying food shortage. According to Sonoda Hiroshi, an official at the Colonial Bureau, "two-thirds of the country's land area is covered by mountains and is not suitable for people to live or farm, so when we look at the suitable places for habitation, the population density can be said to be unparalleled in the world" ("Colonial Issues," Fukuoka Nichi Nichi Shimbun, May 11, 1918).

At that time, Japan was no longer able to develop new lands, and while it was overpopulated and had a population density that was "unparalleled in the world," it was unable to expand its territory as an island nation, and was stuck in a dead end. Therefore, it had no choice but to look abroad. There were other economic problems caused by events such as wars and natural disasters, but in addition to these traditional theories, the author speculates that people who were dissatisfied with the Meiji era, including "areas that were exhausted by the fierce battlefields of the Boshin War and the subsequent samurai rebellions" and "people who were dissatisfied with the Meiji Restoration, which was a trend toward the Freedom and People's Rights Movement," in other words, "areas that were 'rebels' or 'losers' of the Meiji Restoration," may have migrated to Brazil. This point is worth considering, and further research in this area is expected.

Other notable features include the positioning of socially persecuted classes as "a major by-stream of Meiji-era Japanese society," the inclusion of "people from discriminated communities," which had previously been considered taboo, and detailed descriptions of Japanese immigrants to Brazil, such as "Okinawans" and "hidden Christians." The author seems to have hesitated to write about sensitive issues such as people from discriminated communities, but he "knew it was impossible and went ahead with it."

It is only thanks to the author's bold decision that we are able to understand the "essential part" of Japanese immigration history. In addition, the brief chronology at the end of the book, which juxtaposes events in Japan and the world, is a simple summary of the content discussed in the main text, and conveys the author's enthusiasm to show the close exchange between Japanese history and world history (related to Japanese immigration).

In this book, the author, who is the current editor-in-chief of the Nikkei Shimbun, echoes the words of a former editor-in-chief of the same company, "Japanese immigration is a grand ethnological experiment...I am interested in how the Yamato people will change after being thrown into the melting pot of Brazil." He has focused particularly on "writing the opening section of how this grand experiment began," and writes in the preface that he will not touch upon much about the "results of the experiment."

Certainly, there is consistency in the approach and awareness to explore the roots of Japanese immigrants, such as "why and what kind of Japanese left Japan." However, if I may add, I think that if there had been even a little explanation of the process of this grand experiment, that is, "how things changed" as the former editor-in-chief put it, our understanding of Japanese immigrants in Brazil might have progressed a step further.

For example, the "anti-Japanese problem" or the "problem of Japanese immigrant exclusion" is a good example. This can be called the "B side" of Japanese history or the "truth lurking behind the scenes" of immigration history, and it manifested itself in the first half of the 20th century in the United States as well as in Brazil and Peru, wherever Japanese immigrants ended up. Even in Brazil, an article dated April 30, 1912, by a man named Luis Gomes, had already appeared in the Brazilian newspaper (Jornal do Brasil) in which he denounced the Japanese as "an ugly yellow race that is the polar opposite of the ideal of Aryanism," an "inferior race," and an "unassimilable race."

Politically, in 1917, less than ten years after the immigration, the young and energetic politician Mauricio Paiva de Lacerda caused a problem over the contents of the contract for the construction of the Japanese colony. Later, in 1923, Fidelis Reis proposed a bill to restrict immigration, commonly known as the "Reis Bill," and although no trouble was caused at the time, after the 1930 revolution and Getulio Vargas became president of the provisional government, various factors made things worse for Japanese immigration to Brazil, and finally in 1934 the "Law restricting foreign immigration to two percent" was passed and put into effect.

Conflicts such as the anti-Japanese issue usually arise due to some kind of causal relationship. As for early Japanese immigrants, there were significant differences not only in language but also in customs and habits. Japanese immigrants were described as hardworking but also barbaric and uncivilized, and it is true that Miura Saku and other Japanese people called for improving the quality of their immigrants. (Osaka Asahi Shimbun, Hakusai Immigrants and the Key to Improving Quality, Vol. 1 and 2, June 21-22, 1924) The foundation of the current Japanese community of about 1.9 million people in Brazil was the tireless efforts of the Japanese immigrant predecessors who overcame indescribable difficulties in the past, but we must not forget that behind this was the anti-Japanese issue, an event that Japanese people tend to turn a blind eye to.

In this book, the author cites "the activities of Japanese immigrants and their descendants while in Brazil" as a "gap" in the history of Japanese immigration to Brazil, so to speak, within the continuity from the past to the present. If this is the case, the author's investigation into "the beginning of the grand experiment of Japanese immigration" will surely be an important clue to filling that gap.

However, in order to fill the gap mentioned above, it is necessary to conduct a thorough historical study and examination of the activities of Japanese immigrants and their descendants while they were in Brazil. This will be a future issue for research on Japanese immigrants to "Brazil."

Although I agree with what Wang Shu said, it is a pity that there are no references. In addition, I would have liked some reference to the history of the relationship between Japanese immigrants in Brazil and other foreign immigrants, although this is a personal interest of mine. However, these points do not diminish the value of this book in any way.

In any case, it is not easy for a reviewer to thoroughly review the wide-ranging content that the author discusses in this book. However, he takes a comprehensive and bird's-eye view of the history of Japanese immigration from an unprecedented perspective, and questions the state of immigration by linking it to the issue of foreign workers, including Japanese-Brazilians, working in Japan today. Furthermore, he speculates that if immigration history is positioned within the context of modern Japanese history, it will also bring about a change in the "island nation mentality" of the Japanese people.

In any case, it is expected that this book will act as a catalyst to accelerate the development of research into immigration history. In this sense, the book "Immigrants and the Japanese: From the 110-Year History of Immigration to Brazil" is a valuable resource for anyone interested in Brazil, and is well worth a read.

*This article is reprinted from the Nikkei Shimbun (August 2, 2019).

© 2019 Kiyokatsu Tadokoro, Ryo Kubohira