American soldiers with bayonets at the ready, along with bulldozers, cranes, dump trucks, and trucks, appeared at 4:30 in the morning on July 19th, before the sun had fully risen. Since the confiscation had been scheduled for the previous day, the 18th, one landowner commented, "We had expected it, but we let our guard down before dawn" (Ryukyu Shimpo, July 19th, 1980, Evening Edition).

At 5 a.m., work began on putting up barbed wire around the farmland, and supporters and newspaper reporters were pushed out. The American soldiers who entered the farmland showed no ears to the complaints of the residents, and the elderly who were sitting there were easily lifted up and removed from the scene.

If they resisted, they were hit with the butt of their guns and pushed away. Newspaper reporters tried to take photos, but the American soldiers confiscated their film. Some reporters even had their cameras taken away. Sawaji, who was 23 at the time, tried to resist desperately, but was held back by several American soldiers and was helpless.

After a moment of silence, Sawatari murmured, "Being a fourth-class citizen is really tough." It is said that in prewar Japan, people from the Ryukyus, Ainu, Koreans, and Taiwanese were called second- and third-class citizens and discriminated against.

When the reporter repeated, "Are we fourth-class citizens?", Sawaki replied emphatically, "But isn't that right?" "They wouldn't even listen to us. We weren't treated like human beings. We're not third-class citizens. We're fourth-class citizens," he said, looking down.

Despite the residents' desperate resistance, at around 10 a.m., their houses were destroyed by bulldozers, and beach sand was pumped into their fields. 24 families lost their land and homes, while 30 families kept their homes but lost all of their fields. Sawatari's family moved to his father's house nearby, while the Tazato family and 32 other families had to sleep in the nearby elementary school.

After elementary school, the "Isahama refugees" moved to "Innumiadui," a temporary shelter for war repatriates. The area was covered with rocks and was not suitable for farming, and the hastily built wooden houses with tin roofs were vulnerable to typhoons. In September 1981, Typhoon Emma destroyed five of the 14 houses, partially destroyed eight, and only one was safe.

Isahama was a beautiful place and was counted among the three major farmlands in Okinawa. It was fertile land with abundant water and produced high-quality rice. They looked for other places to settle besides "Innumiadui", but could only find worse conditions than Isahama.

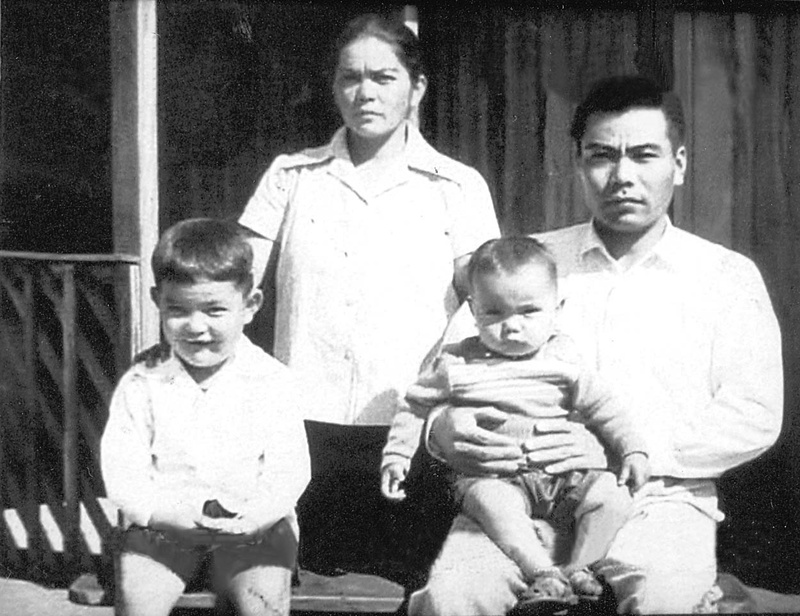

In light of this situation, the Ryukyu government made a plan to relocate the families living in Isahama to Brazil, and 10 families decided to go to Brazil. In the summer of 1957, they departed Kobe on the Chicharenka for Santos City, São Paulo State.

"I no longer had any desire to stay in Okinawa and make a living. The fields were filled with sand, and there was nothing left," Sawaki said, dejected. "When you're drinking at a bar and a dog approaches, you chase it away, right? In the same way, the U.S. military chased us away," he continued.

"We are Okinawans and Okinawa is our island, but as soon as I approached, the Americans yelled at me, 'Get away here!' Why did they have to say such a thing to me when it's the place where I was born and raised? It was really painful. I'm sure you can't understand," she said in a strained voice.

*This article is reprinted from the Nikkei Shimbun (March 16, 2018).

© 2018 Rikuto Yamagata / Nikkey Shimbun