I was surrounded by thousands of passengers; many were Japanese immigrants just like me. But amidst the hustle and bustle of all these travelers who were at once paralyzed with fear of the unknown and eager with hope of a better life, I never felt more alone.

At nineteen years old, my parents decided I should travel to America and marry a man they had chosen for me.

“Hatsumi, you will live a good life with many material things. The Kumagais are very successful and make a good living.”

Their words weighed down on me more as a death sentence than as promise of prosperity. How could I leave my home? Alone? How could I live in a place I do not know? With a language I do not speak? I wanted to cry out, “Please don’t make me do this!”. But I did not say a word because I knew it was shikata ga nai, that which is determined and cannot be helped.

As the S.S. Chichibu Maru pulled out from the Yokohama dock, I was left staring into the vast, unforgiving ocean. I felt so small and helpless that, for a brief moment, I considered jumping over. I quickly realized that that was not an option; I could not shame my family. They had made these plans for me and I was honor-bound.

On May 10, 1931, I arrived at Angel Island for the inspection from the Immigration and Naturalization Service. The experience was horrendous to say the least. I cannot bear recounting my memories there.

Ten days later, I arrived in Palo Alto, California and I was handed an Arrival Action Sheet:

Name: Imagawa, Hatsumi

Destination: Palo Alto, California

Vessel: Chichibu Maru

Date: May 20 1931

Class: Native

Those last words, “Class: Native,” reminded me of a forgotten past. Though I considered Japan my home, I was actually born in Alviso, California. My parents were immigrant farm-laborers growing strawberries in Alviso. I could not remember much of my early childhood, except that a Chinese neighbor who befriended my younger sister, Shizuye, and I would give us candy when we visited her. Growing up in a family that did not have much, this was the only time I had sweets. When I was six years old, Shizuye and I were sent to Fukuoka, Japan to be raised by my grandparents. Since then, Japan was home to me. Japan was all I knew. How ironic it was to come to this foreign land and be labeled a Native!

Upon my arrival, I was immediately delivered to the Kumagai household where I met my husband-to-be Toyotsugu, his parents, his uncle, and his siblings. Toyotsugu seemed even more uncomfortable with the situation than I was. Years later, I learned that Toyotsugu’s parents had arranged his marriage secretly. He was unaware of the engagement until the day I arrived. Despite all this, we were married the next day.

The Kumagais lived in a small house in San Martin and worked on a farm growing pears, strawberries, blackberries, raspberries, loganberries, and boysenberries. They were a very traditional family and as the daughter-in-law I was expected to rise before everyone and stay up until everyone had gone to bed. My in-laws did not give me any money so they bought things for me as they saw necessary without asking my preference. I was responsible for all the lowly and burdensome tasks in the household. As a Japanese immigrant in the U.S. and a daughter-in-law, I felt like a stranger in my community and in my family. I had no one to turn to and nowhere I could run.

Two months after my marriage, I was pregnant. I was often afflicted with dizzy spells, but no-matter my illness I had to continue working in the fields with the rest of the family. I did not want to complain or let anyone know I was suffering because I knew my labor was needed. In one hour, I could pick one crate of berries and that earned 20 cents.

Floyd was born on April 10, 1932. Within the next four years, I had two more children: my daughter Setsuko was born in 1933 and my son Yoshimi was born in 1936. Some days I would question the purpose of my endless toil in the fields, but seeing my children clothed, fed, and educated with the money earned from the farm reminded me that they were my purpose. Born and raised in the U.S., they secured me to this foreign land.

Three years after our marriage, the Kumagais decided to move back to Japan. Toyotsugu refused to go with them because he did not feel close to his family; he was determined to succeed on his own in America and show his independence. My heart was being pulled in two directions. Japan was my home and I yearned to return to its familiarity. I longed to have that sense of belonging and community again. However, I had no desire to be living under the same roof as the Kumagais any longer. In the end, we ended up staying in America.

We farmed on leased land in Palo Alto growing spinach, lettuce, celery, sugar peas, and raspberries and delivered the produce to local markets. Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, Toyotsugu would wake up at 4 a.m. to deliver to San Francisco. He soon learned that he had to speak English in order to run his business, so he attended night school after work to learn the language. The exhaustion from long days in the fields quickly caught up with him, causing him to fall asleep during class. Despite his tiredness, Toyotsugu still made time for leisure. In addition to his English classes, he also attended dance and singing lessons.

In 1939, our fourth and last child, Yooko, was born. Floyd and Setsuko began attending school and soon grew proficient in English. They became our interpreters. As the children grew up, they began helping on the farm. Floyd helped Toyotsugu water the plants early in the morning and Setsuko helped me cook. The children had their fun too.

I would often catch Floyd nailing wood planks to the side of the house so he and his siblings could climb to the roof of the house. The children would ride together on our horse Queenie. They loved that! Our family got to know the neighbors pretty well too. At two years old, Yooko would go speak with Mr. Coulbraq, the French man who leased the land to us, in Japanese and he would reply in French. What a sight that was!

I finally started to feel a sense of belonging. I finally felt like a part of the community and things were looking up on the farm. I was hopeful for our future.

Afterword

After President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which provided for the evacuation of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, the family’s life was drastically disrupted. They moved to Newcastle, CA, near Placerville, which for a time was an area Japanese Americans were allowed to live. In July of 1942, the family was sent to Tule Lake camp in far northern California. Daughter Mary Kumagai-Hyodo-Polk wrote, “Although the Japanese Americans were able to build a community and live in harmony within the borders, it was a situation that no American should go through. Their liberty and rights were taken away. The whole constitution is built on democracy and freedom for its citizens.”

After the war, the Kumagais were finally released from Tule Lake on February 14, 1946. After difficulties finding a place to live because no one would rent to Japanese Americans, they were able to buy an old barrack from the Repetto family in Palo Alto, whom they had known before the war. Toyotsugu helped many other Japanese American families return to the area by providing them a place to live. At first Toyotsugu made a living from gardening and Hatsumi did housekeeping and sewing. Starting in 1947, the family then built a chrysanthemum business and developed award winning flowers. In the late 1950s their US citizenship papers were reinstated (the government held the papers until our attorneys fought back for them). They retired in 1969 and moved to Los Altos Hills, then back to Palo Alto in 1979. Hatsumi passed away in 1999 and Toyotsugu in 2001.

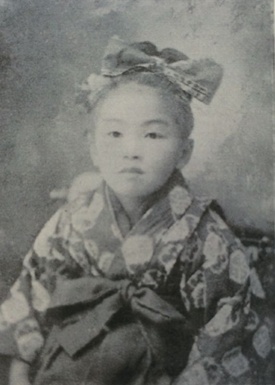

*This article was originally published on Immigrant Voices by the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation. All photos are from Kumagai/Imagawa written by the Kumagais’ daughter Mary Kumagai-Hyodo-Polk.

© 2018 Jennifer Chen