A moment with an immigrant family

"You'll go to Cafe Senasuka. What about you?"

"You can go to Almosa too."

This is how the first generation elder, a prewar immigrant, welcomed me whenever I visited him as a student studying abroad from Japan. His wife, who danced Japanese dance in the women's group and enjoyed haiku, was always there, smiling. In addition to the two of them, their second generation daughter and daughter-in-law, and sometimes even their third generation grandson, a junior high school student who spoke broken Japanese, would also be present, and although they would sometimes switch places, they always treated me like family. Finally, we always had a meal of ochazuke and pickles. Meeting the kind old man, whom I will never see again, and his family was a distant and nostalgic memory, an experience that was truly worthy of the expression Brazilian saudade (nostalgia). It must have been a very comforting time for me, living alone in a foreign country.

Now that I am working on immigration research, I regret that I did not think of recording or recording that conversation at that time. No, that would have been rude, and I did not have the time to look at that family as a research subject. Incidentally, the opening sentence means, "I'll have black coffee (without sugar), what about you?" and "You can have lunch together." "Yo" is not the "I" in the lordly language "I am satisfied," but a corrupted version of the Portuguese first person singular "eu" (I). At first, I wondered if my ancestors were...

It has been more than 30 years since then. Around the same time, I interviewed a second-generation Japanese woman for my master's thesis, and I still remember the shock I felt when she said, "It's the word 'gratitude.'" This was her answer when I asked her what she thought was the most important part of the Japanese culture and heritage she inherited from her first-generation parents. About 20 years later, this word "gratitude" was rephrased as "okagesama de" and was heard by Japanese people in Hawaii. And the English translation by Japanese people is a wonderful and wonderful translation. I am what I am because of you. "I am who I am today because of you." I felt that I had learned the emotional anchor of being Japanese and the values of everyday life as a tradition of Japanese culture through Japanese people. This is a unique outcome for Japanese people who have struggled and clashed in different cultures and multiculturalism, and have sought and condensed the anchor of Japanese culture. There are Japanese people who understand the meaning of "okagesama de" even if they cannot speak Japanese. It is very significant that this word has been passed down.

Brazilian Colonia

Let's go back to the champon language mentioned at the beginning. In Brazil, it is called Colonia language. Colonia is a Portuguese word that originally means "colony." However, after World War II, Japanese immigrants who were barred from returning home decided to live permanently in Brazil, and from the time they sought ways to cooperate and survive, the term "Nikkei Colonia" came to refer to the entire Japanese community. Colonia language refers to the language used in the Japanese colonia, a Japanese language mixed with Portuguese that was spoken among the first and second generation Brazilians. Some expressions I still remember clearly are as follows:

"Turn right at the next esquina (corner) and go straight down that street, which will take you to Vargas Street."

"Then let's play tennis together next Sunday."

"The onibus (bus) won't be coming for a while, so let's grab a taxi over there."

The underlined expressions are unique expressions that arise from directly translating the Portuguese verbs used in each situation into Japanese. Ms. Seiko Sasatani of the Curitiba Model School calls the Colonia language "Japongeis" (a pun on the words japonês and português), and gives the following examples:

“I’m retired now, so I go fishing during the week and have lunch at my son’s house on Sundays. I have a stable life.”

(Kakehashi no. 21, 2013, p. 18)

Even among Japanese poets, there are words in Portuguese that have been mixed into Japanese and become seasonal words.

My child's noiva (bride) is a big woman by Seiryuko Aoyagi.

The days of pickling papaya and stems are long gone.

I feel lonely after taking a shower and go to bed.

(Ushidoji Sato, "Brazil's Almanac" 2006)

In addition, words such as "joro (noko)," "ai no ko," "gaijin," "toilet," and "yoriai" (a word that is rarely heard in everyday life in Japan today, or that are words of the past, were often heard in the Japanese colonies. They are words that seem to have been frozen in time and remain as they are. Incidentally, "ai no ko" was the title of a video introducing the Japanese community produced in Londrina, Paraná in 2000, and was expressed as "children of love" (filhos do amor). The derogatory meaning of the word ainoko has been transformed and given a positive meaning. In terms of the transformation of the value of words, japa (japa) is also one example. This word, which corresponds to the English word jap, originally had a derogatory meaning. However, in Brazil, probably since the 2000s, a situation has emerged where it no longer has any derogatory meaning at all, and is understood by both the user and the user as a word of familiarity. This means that the situation in which it is viewed as an object of contempt has decreased. There must be a deep connection with the contributions of Japanese people in Brazil.

In addition, I have often felt uncomfortable being called "uncle" by people almost the same age as me. There must be women who have also felt uncomfortable being called "auntie" by people of the same generation. This is an unfortunate mistranslation of the Portuguese words tio (uncle) and tia (auntie) that are sometimes used to call people you do not know. In this case, the assumed age range of the Portuguese words tio and tia is quite wide.

Or, I once saw a job advertisement for a "bodyguard wanted" at a dekasegi-related consultation center. It was written in bilingual language, and in Portuguese it said "Procura-se um guarda." Looking into the details, it said that the advertisement was for someone to take care of their small rural farms to prevent them from being vandalized or stolen while they were away as dekasegi workers. Indeed, guarda means a sentry or guard, and in Brazil, it may be necessary to fire a gun in some cases. I was impressed by how well the advertisement was described.

"Lukikechi" and "Osumadayo"

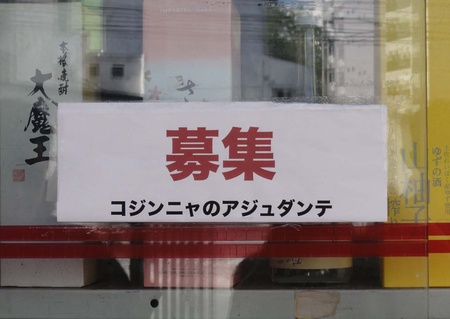

I'm sure there are few people who know what Lukiketsi and Osumadayo are. The former is "Colonian language" and the latter is "Yokohama dialect". Lukiketsi can be said to be a type of Colonial language. As you can see in the photo, this is the name of a store. A store called Lucky Cat also writes its name in Japanese, and it is displayed as "Lukiketsi". This is presumably derived from a Brazilian English pronunciation (?). This is because it is the same as the sound change that comes from the way many Brazilians pronounce (or sound like they pronounce) party as parchii, Yakult as yakuruchi, Hello Kitty as haro-kichi, and Batman as batchman. The fact that it is displayed boldly as a store name shows that it is not perceived as unnatural at all.

Yokohama-kotoba refers to the language that was used between Japanese people who had contact with foreigners, mainly in the settlement, after the opening of the port of Yokohama in 1859, and is recorded as "Yokohama-kotoba". Among these words are "kankan (count, see the distance), "chinchin (change, see the distance), and "hamachi (how much, see the price). One theory is that "champon" is also a Yokohama-kotoba. However, "osumadayo" is a little difficult. This is said to be a transliteration of "What is the matter with you?", which means "What have you done?". It certainly does sound like that when you pronounce "What is the matter with you?" quickly. This may be what it means to learn by ear. It is not difficult to imagine that some of the immigrants who went overseas from Yokohama passed on the vocabulary they learned from their experiences in Yokohama. The connection to Hawaiian pidgin English is also of concern.

This history shows us the hardships that immigrants faced and overcame, and that what may seem comical today was actually a huge struggle.

© 2018 Shigeru Kojima