At a time when history presented a favorable scenario, the growth of the city of São Paulo and the consequent change in the routine of São Paulo residents, the Cooperativa Agrícola de Cotia (CAC) emerged. One of the largest Brazilian cooperatives, CAC contributed to the cultivation of potatoes, soybeans, grapes, mangoes and coffee, in addition to the production of eggs and chicken.

The emergence of agricultural cooperatives

According to historian Célia Sakurai, “Japanese families came to Brazil and, after those years of contracts on coffee farms, acquired small pieces of land”. And the survival of these families depended on the production coming from this land.

Colonies were thus formed, small properties grouped in some locations, because the land was all neighbors. This neighborhood provided the possibility of opening a school, association, etc. So life revolved around these new communities.

In general, as these colonies were located in a certain region, the same thing occurred. This is the case of cotton, some coffee farms, small producers and tea in Registro, in the interior of São Paulo.

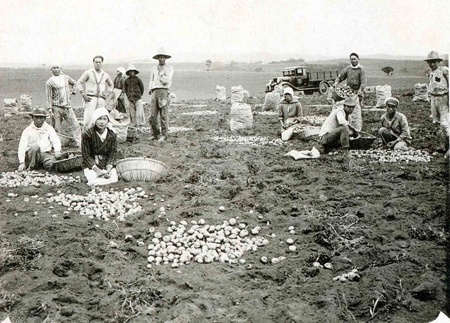

One of the biggest highlights in the history of cooperatives is the Cooperativa de Cotia, in Greater São Paulo, where families began producing potatoes. They are small producers who later started to come together to sell in São Paulo. “The role of the cooperative is not production, but marketing. Because each family produced on their own land and marketing was difficult”, says the historian.

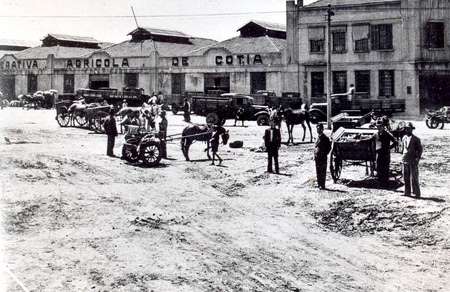

“Today, Largo da Batata, in Pinheiros, was the place where producers from Cotia took these potatoes to be sold in the city of São Paulo.” There, this small potato marketing center began to emerge, which gradually grew, and generated a certain decentralization of food trade in the city, because it did not necessarily happen in the Central Market.

Expansion: from Cotia to Brazil

Production began in Cotia and later expanded to other places, such as the interior of São Paulo, because the cooperative system facilitated the flow of products.

An offshoot of the Cotia Cooperative is egg production. As the Cotia market was very small, these small farmers then began to get together to produce eggs and sell them to the city of São Paulo. What made it easier was the fact that the cities were close to each other.

In addition to eggs, they began to raise chickens from some matrices that were brought from Japan. The potato – which went through an improvement process and, therefore, techniques to combat pests were developed, among others – the egg and the chicken were the three main products that took advantage of the market in the city of São Paulo. In the 1930s, early 40s, it was a time when the city was growing and that's why the Cooperative was successful.

Until the 1930s, people ate eggs from the chicken they raised in their backyard. However, with the growth of the city, and consequently with activities that did not leave time for people to produce their own food, there was a need to visit places to be able to buy these products. “It was precisely at the time when the Japanese came to São Paulo and started selling these products that were previously part of the daily lives of housewives”, he explains. The same happened with the stallholders who sold vegetables.

Later, in the 60s and early 70s, the expansion of the cooperative reached other regions of Brazil. This is another side of the cooperative's work, which is to open new frontiers.

In the 60s and 70s, at the time of the military government, it was interesting to create new frontiers for the settlement of people that until then were not within the Brazilian economic map, such as, for example, the cerrado region.

The military gave a piece of land to the Cotia Cooperative, which built an experimental block in the city of São Gotardo, in Minas Gerais. The farmers started with a pilot project, trying various crops. Today, there is coffee from the cerrado and wheat and soybeans are planted, products that began to be tested by the cooperative's technicians. “The Cooperative had a fantastic plot to produce the matrices of soybean seedlings and today they are spread throughout Brazil”, he says.

CAC had a hub in western Bahia, in Barreiras, which has a large production of soybeans. Today it produces a lot of grapes and mangoes for export, as well as wine produced in the São Francisco River valley. All of this was also a project of the military government together with the second generation of Japanese families (the first generation was the one dedicated to potatoes, chicken, eggs), who went to some uninhabited or uneconomical regions to test some crops.

Furthermore, the Cotia Cooperative expanded to the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro and created a warehouse to supply the city.

Success of cooperatives

Célia Sakurai states that the Japanese contributed greatly to breaking the landlord system, with the idea that agriculture is equal to large property. Small or medium-sized properties produce and can also be profitable.

Today there is an urban population, where people with the most varied types of work live. Thus, for the historian, Japanese immigration was successful for Brazilian public opinion due to a historical coincidence. The Japanese arrived in São Paulo – which in the 1920s-30s was the locomotive of Brazil because of coffee –, which in some way favored this social ascension, which began in agriculture and with the organization of cooperatives that were completely unknown. by Brazilians.

The idea of cooperatives, of mutual aid, has always existed in Japan and immigrants brought it from there. It was even “natural” for this first generation to organize itself in these community groups and then teach it to the following generations.

As soon as they settled, the immigrants stopped dreaming of returning to Japan, because “Brazil, despite all the odds, opened up possibilities for choosing. You could choose where you wanted to go. I could buy land, choose where I wanted.” In Japan, the choice was much more restricted.

Community

“From 1928 until 1960, the beginning of the 70s, the Japanese created an aura around themselves that they were great producers, good farmers, because they were organized and hardworking”, he says. There is, therefore, a stereotype that the Japanese are great workers, great farmers, and that they are trustworthy.

This stereotype arose because the process of social ascension was visible. “From that small piece of land people produced and worked, their children studied, they bought a better house.” It was another mentality and one that focused on the idea of becoming a land owner.

Another point that involved the community was the fact that the cooperative had an idea similar to that of kaikan , an association, in which everyone helps and participates in group activities. The associations also help build schools, pay teachers, with the aim of having something community-based that works. It is “a journey that comes from Japan and continues in Brazil”, adds the historian.

Cotia Agricultural Cooperative

Created in December 1927 under the name of Sociedade Cooperativa de Responsibility Limitada de Produtores de Batata em Cotia S/A, the cooperative had 83 farmers.

Until 1942, it stood out among other companies in the sector, diversifying its production by selling other products, such as fruits, eggs, grains, poultry, vegetables, tea, cotton and legumes.

Its expansion occurred from the end of the 1930s throughout the State of São Paulo, the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, Paraná and Minas Gerais.

With 60 years of existence, in 1987, CAC already operated in 15 states, with ten cooperatives linked to the center, 90 regional deposits, in addition to 15 thousand members and annual revenue of 760 million dollars.

In 1994, the cooperative decided to dissolve by free will and, four years later, the cooperative's archives were donated to the Historical Museum of Japanese Immigration in Brazil, in São Paulo.

Reference:

TANIGUTI, GT "Cotia: Immigration, Politics and Culture". Thesis (Doctorate) . University of São Paulo, Faculty of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences, São Paulo, 2015.

© 2017 Tatiana Maebuchi