The harsh winds of autumn

Pierce the spirit of those

Who live at the mercy of fate

Created by the war.Akiyama1

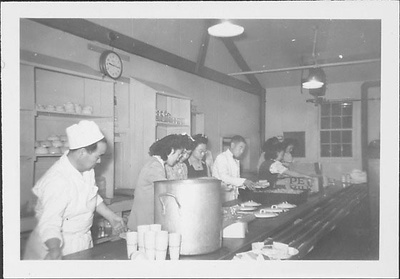

The internees had primitive living conditions. The North Portland Assembly Center had previously been used as the Pacific International Livestock Exposition Building and was barely adapted for human habitation. Each family was assigned to a small, single room in a large barrack with walls made of thin plywood sheets. In order to make each room as “homey” as possible, the internees made shelves, tables, chairs, cupboards and other furniture and appliances for themselves. They hung curtains or put up screens to separate sleeping quarters between adults and children. Despite those efforts, privacy was non-existent. The sound from neighbors was heard continuously, and washing, toilet and shower facilities were shared by other residents of the barrack. They also ate their meals at mess halls.2 These conditions remained much the same even after the people were moved to internment camps.

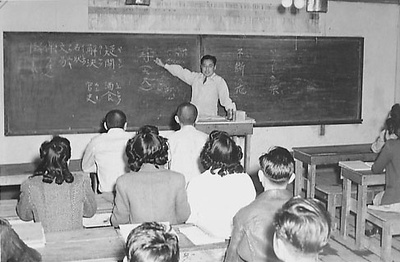

During their incarceration, the life of the Issei completely changed. The camp authorities provided meals and basic daily necessities, as well as some spending money. Consequently, the Issei were not required to work for subsistence, although many of them volunteered for skilled and unskilled employment for which they were paid minimal wages set by the government.3 The wives’ domestic duties included family laundry and room cleaning. Childcare took less time because given the small living quarters, the children tended to spend their time outside, playing and eating with friends. This disrupted the close knit family life which characterized Japanese families, although it enabled the Issei to engage in various recreational activities ranging from English learning to creative arts.4

In February and March, 1943, the War Relocation Authority (WRA) conducted the “army enlistment and leave clearance registration” in order to separate the “loyal” internees from the “disloyal” ones. In the questionnaire administered to the internees, question number 28 asked if they were willing to “forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor.” From the Issei perspective, this question only reinforced the dilemma that had haunted them since Pearl Harbor. Because the Issei were “aliens ineligible to citizenship” in America, it virtually forced them to become persons without a country. Some were also afraid of the possible consequence of family separation, while others worried about the welfare and future of their children.5 After considering all these factors unrelated to their “loyalty” to America, the vast majority of the Oregon Issei answered “yes” to this question.6

Through this questionnaire, the WRA also intended to recruit Nisei volunteers for the Army. Thousands of the Nisei from ten internment camps served in the military to vindicate not only themselves but also their parents. Along with the Nisei from Hawaii, they formed the 100th Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and fought in the European theater, during which time they earned the distinction of being one of the most decorated combat units. In the Pacific theater, a few thousand Nisei served in the Military Intelligence Service, utilizing their Japanese language skills to interrogate captured enemy soldiers and translate documents. Among them was Sgt. Frank Hachiya of Hood River who received a Distinguished Service Cross for uncovering the Japanese defense lines in the Philippines at the cost of his own life.

Notes:

1. A Santa Fe Internment Camp Scrapbook, in George Azumano Personal Collection.

2. See Janet Cormack, Ed., “Portland Assembly Center: Diary of Saku Tomita.

3. Internees were paid $12.00 for unskilled work, $16.00 for skilled work and $19.00 for professional work.

4. Marvin G. Pursinger, “Oregon’s Japanese in World War II, A History of Compulsory Relocation,” p. 180; and Janet Cormack, Ed., “Portland Assembly Center: Diary of Saku Tomita,” pp. 158-159, 163.

5. Eileen Sunada Sarasohn, The Issei: Portrait of a Pioneer, An Oral History, pp. 208-209.

6. WRA, The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description, pp. 162-165.

* This article was originally published in In This Great Land of Freedom: The Japanese Pioneers of Oregon (1993).

© 1993 Japanese American National Museum