A series of exclusions

Now getting used to it

I spend each day farmingHonda Fugetsu1

While building their community and industries, Japanese immigrants struggled against exclusionists’ threats. Combined with the rise of anti-foreign sentiments of World War I, the rapid growth of Issei agriculture stirred whites’ fear of Japanese competition. As the Hood River Japanese farmers showed a notable prosperity with a high level of land ownership, they became the prime target of organized exclusionist attacks. The local American Legion was the forerunner of the movement. It not only opposed Japanese land ownership in Hood River but also called for state and federal laws to strip them of legal rights in farming. In 1919, under the leadership of the Legion leaders, the Anti-Asiatic Association was organized, in which most of the prominent citizens of Hood River participated, pledging neither to sell nor to lease land to the Japanese. As the chief reasons for Japanese exclusion, the organization cited the rapid growth of Japanese land holdings, their economic threat to white farmers, high birthrate and low standards of living.2

(Courtesy of R. Rose, Japanese American National Museum [92.162.13])

Masuo Yasui stood up for his fellow Issei residents in Hood River. He first refuted the charge of Japanese “domination” by citing the fact that a total of 70 Japanese farmers controlled only two percent of all farmland in the Hood River Valley. Yasui also took issue with the Anti-Asiatic Association’s figure of 800 Japanese in the county. Referring to the figures of the 1920 U.S. Census and Japanese Consulate Report3, he estimated the presence of 362 Japanese in Hood River, which was in fact a reduction of more than a hundred since 1910. The relatively high birthrate, he stated, was because most of the Issei had just started their families during the past decade. Lastly, he blamed white landowners for the low living standards of Japanese farmers, since they were the ones who provided the ill-equipped dwellings for the tenants.4

In an effort to better their community and to make white Americans accept them as equally civilized people, Yasui also compiled a list of his “requests to Japanese ladies,” which he probably distributed to other Issei.5 After asking the women to “cultivate common sense,” he argued, “You, the Japanese wives are the ‘diplomats’ who represent all Japanese women, and you have greater influence than the Japanese government officials.” Yasui then warned the Issei mothers not to leave their children unattended while working in the field. Rather than to make a fuss over money, he urged them to pay more attention to the care of children. In the end, he also added, “These are applicable not only to the women. I hope their husbands…will take the lead.”

Hoping to settle the agitation once and for all, the Issei of Hood River entered into direct negotiation with the Anti-Asiatic Association. As their representative, Yasui delivered a proposal to stop voluntarily further Japanese land ownership and migration into Hood River in return for the cessation of the agitation.6 After making that proposal, he contended that no one could blame his fellow residents for wishing to remain in the valley where they had established their families and farms for years. In order to live in harmony with their white neighbors, the local Japanese were eager to enter any agreement based on fairness.7 Nevertheless, the exclusionist group chose to seek discriminatory legislation against the Japanese rather than bring the local friction to an end.

During this period, anti-Japanese agitators succeeded in stopping the expansion of Japanese farming activities in other locales. Central Oregon was a case in point, in which ever the powerful “Potato King,” George Shima, was forced to give up farming. In 1919, he and two white entrepreneurs purchased 13,800 acres near Redmond in the Deschutes Valley. He brought a handful of Japanese potato experts and field hands to raise the seeds for his California farms. This move upset the local white farmers as they saw “the acquisition of land by Japanese tenants and labor” as “detrimental to the best interests and the American farmer and businessman.”8 Forming the Deschutes County Farm Bureau, they stood against the project. Encountering the county-wide opposition, Shima was forced to promise to neither introduce Japanese immigrants nor sell the land to them. Between 1922 and 1923, similar organized movements kept Japanese immigrants from settling in Prineville near Redmond, as well as in Medford near the California border.9

In the Oregon state legislature alien land bills were introduced in 1917, 1919, 1921 and 1923. The Anti-Asiatic Association, the Oregon American Legion, the Ku Klux Klan and opportunistic politicians were among the bills’ major endorsers. Using the term “aliens ineligible to citizenship,” the goal of these bills was to prohibit land ownership and leasehold by Japanese immigrants.10 Since the majority of Japanese farmers, except in Hood River, were still tenants, the alien land law, if enacted, was likely to hinder their economic advancement.

Japanese immigrant leaders made every possible effort to prevent the enactment of the bills. They hired a white lawyer and sent him to the state legislature to lobby on their behalf. At the same time, they sought the support of the Portland Chamber of Commerce on the issue.11 Having an economic stake in international trade with Japan, the Portland businessmen were eager to use their political influence on behalf of Japanese immigrants. Their involvement created enough support to kill the first three bills before enactment.

The Issei leaders believed that they would be vindicated if they continued their struggle against exclusion. Senichi Tomihiro, a Portland leader, wrote after the 1917 bill was shelved:

It seems unlikely that those anti-Japanese agitators suddenly will change their minds and that the issue will disappear. If an alien land bill is introduced every year, we have to fight it to the death each and every time and protect our right to own land… Hopefully, during that time, the “flowering spring” will come with a fundamental solution for the right of naturalization.12

Despite such a hope, however, between 1922 and 1925 the Oregon Issei encountered a series of oppressive statutes and practices by the federal and state governments, as well as violence from the exclusionists. In 1922, the United States Supreme Court ruled that a Japanese immigrant named Takao Ozawa was not eligible for citizenship because he was non-white.13 With this decision, the United States officially established the legal status of the Issei as “alien ineligible to citizenship,” thereby making them virtual second-class citizens.” Two years later, based on this classification, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924 which prohibited the further entry of Japanese immigrants.

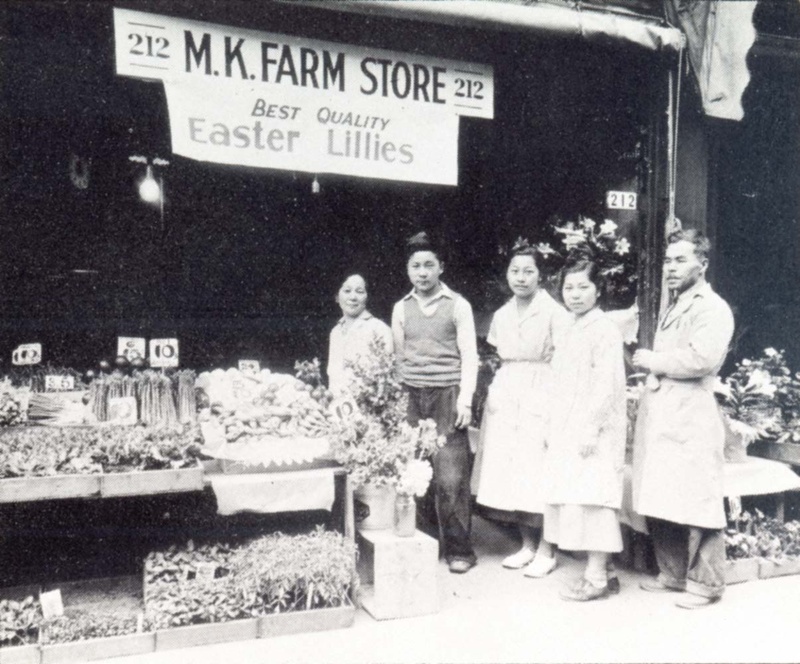

In 1923, the state of Oregon enacted two laws that discriminated against the Issei: the Alien Land Law and the Alien Business Restriction Law. The former legislation aimed to reduce Issei farmers to common laborers by prohibiting their land ownership and leasehold. The Alien Business Restriction Law attempted to destroy Japanese immigrant businesses. It allowed municipal governments to refuse business licenses to aliens for the operation of pawn shops, pool halls, dance halls or soft drink establishments. The law also required grocery stores and hotels run by aliens to display the signs of their nationalities, thereby enabling customers to choose which businesses to patronize on the basis of race and ethnicity.14

The final blow was the infamous Toledo incident of 1925, in which Japanese sawmill laborers were violently driven out of the town by a mob of local whites.15 Although the Issei eventually won a lawsuit against the mob leaders, this incident was a clear message of rejection from the white society. Denied naturalization rights in this country, the Issei were now subject to permanent legal discrimination. Such a grim reality caused the exodus of the Issei from Oregon, probably to Japan. Between 1924 and 1928, their population dropped from 2,374 to 1,568 in Oregon.16 It represented more than a thirty percent decrease.

After the mid-1920s, the Issei’s hope rested with their American-born children, the Nisei. Hood River farmer, Kohei Koana, spoke of it in a sarcastic way:

The Alien Land Law is now strangling us with its devilish hands. Even if such oppression gets eased in the future, we will probably be too old to work on farms by then…. Japanese farmers might disappear from Oregon within the next twenty years, unless the Nisei can successfully take over.17

By virtue of their citizenship, the Nisei had all the privileges and rights which were denied to the first generation. Thus, despite the Alien Land Law or the Alien Business Restriction Law, the Issei could still lease or purchase farmland, as well as operate businesses, in the name of adult Nisei. On the eve of Pearl Harbor, for example, the Japanese farms in Oregon cultivated under the names of the Nisei constituted approximately 81.1 percent of the total.18

During the twenties and thirties, Japanese immigrants devoted themselves to building firm economic and social foundation for the second generation. The Issei believed that the future of the Nisei would be bright if they could succeed economically. To secure their agricultural foothold Issei farmers concentrated on the production of the crops that white farmers ignored.19 Merchants also worked hard in order for their Nisei sons and daughters to get higher education. An Issei woman noted that she and her husband struggled to “send [their] children to college so that they wouldn’t be inferior to Americans.”20 A hotel proprietor also said that he and his wife “kept working silently” despite the frequent insults by their white customers because their “earnest desire was to send [their] children to college by all means.21

By the late thirties, it seemed to the Issei that the Nisei were almost ready to become the successors to the Japanese community. In 1940, when the Portland Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) hosted the National Convention, the president of the Japanese Association of Oregon stated to the local Nisei as well as to the delegates from other communities:

We rejoice that the patience of the first generation is now receiving its reward; that our hope is being fulfilled; that our faith is being justified and that our cherished desires have been realized by the solid formation of your league, especially, your sincere efforts towards betterment of social, political and economic conditions. They are greatly appreciated…. I count upon you to contribute your share to the elevation of the high standard of American citizenship by broadening the traits which you have so proudly inherited from your parents.22

Nevertheless, the Issei’s “hope,” “faith” and “cherished desires” were all abruptly smashed on the fateful day of Pearl Harbor.

Notes:

1. Tachibana Ginsha, Hokubei Haikushu, p. 37.

2. Marjorie R. Stearns, “The History of the Japanese People in Oregon,” pp. 6-9; and Barbara Yasui, “The Nikkei in Oregon, 1834-1940,” pp. 242-244.

3. The 1920 U.S, Census showed the existence of 351 Japanese in Hood River, while the Japanese Consulate statistics indicate 389 Japanese.

4. Barbara Yasui, “The Nikkei in Oregon, 1834-1940,” p. 243; and Marjorie R. Stearns, “The History of the Japanese People in Oregon,: pp. 22-23, 25, 27-28.

5. Masuo Yaqsui, “Request to Japanese Ladies,” ca. 1920, in Yasui Brothers Manuscript Collection, the Oregon Historical Society (hereafter, OHS).

6. Hood River News, January 16, 1920; and Letter from the Anti-Asiatic Association to M. Yasui, January 31, 1920, in Yasui Brothers Manuscript Collection, OHS.

7. Marjorie R. Stearns, “The History of the Japanese People in Oregon,” pp. 25-26.

8. Ibid., p. 9

9. Ibid., pp. 9-13.

10. The alien land bills of 1917 and 1919 did not prohibit Japanese leasehold, but limited it to the maximum of three years.

11. Letter from Senichi Tomihiro to Masuo Yasui, January 30, 1917, in Yasui Brothers Manuscript Collection, OHS. Also see Marjorie R. Stearns, “The History of the Japanese People in Oregon,” pp. 45 and 57.

12. Letter from Senichi Tomihiro to Masuo Yasui, February 14, 1917, in Yasui Brothers Manuscript Collection, OHS.

13. For more details of the Takao Ozawa case, see Yuji Ichioka, The Issei: The World of the First Generation Japanese Immigrants, 1885-1924 (New York: Free Press, 1988), pp. 210-226.

14. Kojiro Takeuchi, Beikoku Seihokubu Nihon Iminshi, pp. 675-677; Taihoku Nippo, February 26, 1923.

15. Tanihoku Nippo, July 24, 1926; Kojiro Takeuchi, Beikoku Seihokubu Nihon Iminshi, pp. 671-673. See also Stefan Tanaka, “The Toledo Incident: The Deportation of the Nikkei from an Oregon Mill Town,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly 69:3 (July, 1978, 116-126.

16. Eliot G. Mears, Residential Orientals on the American Pacific Coast: Their Legal and Economic Status (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1928), pp. 420-421; and Oregon Bureau of Labor, Census: Japanese Population in Oregon (Salem: State Printing Department, 1929). Tally by the author.

17. Tanihoku Nippo, May 14, 1923.

18. Marvin G. Pursinger, “Oregon’s Japanese in World War II, A History of Cmpulsory Relocation,” pp. 430-436.

19. Ibid., p. 46.

20. Kazuo Ito, Issei: A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America, p. 274.

21. Ibid., P. 527.

22. Sixth Biennial National JACL Convention Catalogue, Portland. 1940, p. 17, in Sumiye Kogiso Kobashigawa Collection, the Japanese American National Museum. The JACL Portland chapter was established in 1928.

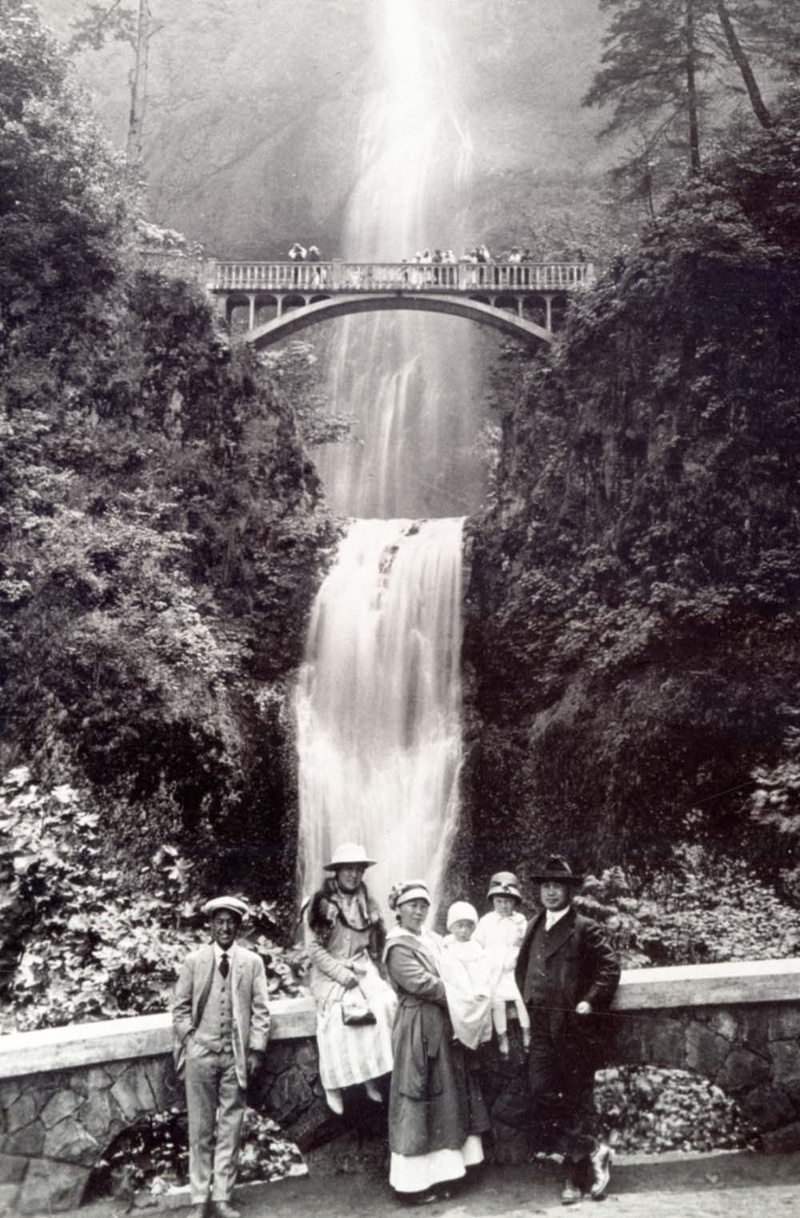

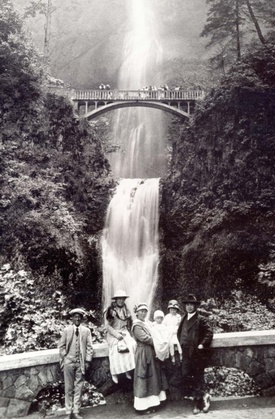

* This article was originally published in In This Great Land of Freedom: The Japanese Pioneers of Oregon (1993).

© 1993 Japanese American National Museum