Beginning of an artistic practice/art career

Where did you go to school?

In telling my own story, I realize that who I am and who I became has everything to do with who my parents were, where they had come from, what expectations they had when they made a choice to live here in Canada, and how it all ended for them but continued toward resolution in my life. Undoubtedly my education began at home, though it also confused me leading to problems of identity issues.

In fact, issues around my own identity was never far away from me, and realizing my inadequacy in even to analyze my own situation, even as I was reading books, in the late `60s, with encouragement from my husband and friends, I registered as a mature student at University of Winnipeg and began my university studies, beginning with emphasis on history, sociology and political studies.

Around this time, a friend asked me if I would join her in attending an art class, being held in the basement of a church where her brother was the minister. I said okay, without much thought, and began taking classes with her. In fact, she quit soon after starting, but I found myself continuing and soon after investigating requirements for acceptance into University of Manitoba’s School of Art.

When I discovered I had some talent in making art, but as well realized art was a way of probing into my own psyche, I submitted a file of hastily produced artworks to the School of Art and was accepted in 1973. I took the usual courses, largely focused on drawing and painting, but in the end majored in sculpture and drawing, finishing with BFA (Hons) in 1977. I then took an extra year in Western Art History. From 1980 to 1982, I went to University of British Columbia to take graduate studies in Asian Art History. This was to investigate Asian cultural heritage. After completion, I was hired at University of Manitoba, as assistant director/curator of the University of Manitoba’s gallery and collection, and later instructed part time in art history.

I spent seven years curating contemporary art in this position, largely works by Manitoba contemporary artists. Interestingly one of the exhibitions held here was based on the Japanese Ukiyo-e prints that Mr. Yoshimaru Abe had collected ostensibly out of antique or thrift shops through the years. I believe this was the first time artists in this area were introduced to Japanese art. The exhibit included a few calligraphies of poems by Mr. Abe himself.

During the same period (mid 1980s), I was invited as art advisor to Inuit printmakers, in Baker Lake, N.W.T. I flew north about three times a year, staying for a period of about a week, helping artists to choose images from their drawings, and produce their annual collection of prints, then meeting with Canadian Eskimo Arts Council which juried the art.

This experience was an eye opener for me. It was not just that the Inuit were people displaced, living as a community in Baker Lake, but that the colonial control was very evident. The print production and sales were totally under the control of the Eskimo Arts Council. I couldn’t help but note that while a major industry in Inuit art was flourishing in the south, the Inuit artists and their families were still living in relative poverty in the north. This was the first time that I began focusing on cross-cultural and intercultural issues, in both art and in society.

After seven years at University of Manitoba’s gallery, I was able to take a sabbatical leave, and so, in 1990, with the Redress compensation funds in hand, I went for a full year to University of Leeds, U.K., to study under a renowned feminist scholar, Dr. Griselda Pollock, and returned with a Masters in Social History of Art (largely a cultural studies program). Since my studies to date had been based on modern art, this was important to catch up to the present which was already focused on post-modern and post-colonial studies.

As a sabbatical leave, I was required to return to my job at University of Manitoba, but received notice as I was planning to return, that the job was no longer there for me “due to economic conditions.” I grieved this termination through the Union believing this was not just about “economic conditions” (but of a woman of ‘difference,’ and a feminist), but then chose to move to Prince Albert in 1992 as Executive Director/Curator of the local gallery, while also instructing in art history at University of Saskatchewan.

I found Prince Albert to be a very interesting city, in northern Saskatchewan. There were several outstanding artists (particularly painters and potters), however, when I arrived I found to my incredulity, no participation in this gallery by Aboriginal artists of Saskatchewan. Soon after my arrival to this position, with support from major local artists, I made arrangements to have Aboriginal artists take part in the annual Art Festival open to provincial artists, including those making art in the cells of the local Penitentiary.

During this time, I met and worked with artist, (the late) Bob Boyer, who was a professor at the Indian Federated College at University of Regina, to produce a travelling exhibition of Saskatchewan Aboriginal artists. It was a wonderful experience introducing artists of various media, including writers, to the community.

After three years, I decided to move to Vancouver (where my aging mother resided), and applied to each of Vancouver Art Gallery and Burnaby Art Gallery for their advertised curatorial positions. I short-listed and was interviewed by both, and took the job at BAG where I spent the next three years. Burnaby Art Gallery’s collection was largely prints, but while there, I focused on curating cross-cultural exhibitions, one titled, Tracing Cultures, a series of exhibitions, including such distinguished artists as Haruko Okano, who, having been raised by non-Japanese foster parents, was dealing with issues of authenticity through meditational practices in her installation art, and Gu Xiong, who immigrated from China to Canada after the Tiananmin Square Incident (1989).

We also held an exhibition of art, and a discussion, related to the Through Women’s Eyes, UN Fourth World Conference on Women, 1995, Beijing China.

During this time, the Japanese Canadian National Museum was in a developmental stage and the then president, Frank Kamiya, asked me for consultation in producing the Museum.

I volunteered my time for several months but, as we were getting ready to apply for the various governmental grants and private funds to develop a national museum standard archival storage system and gallery, curatorial and education programs, a cooperative research centre, and a gallery shop, and to install the inaugural exhibition, all in time for the opening of the Centre in September 2000, to qualify for such funding, I was, in 1999, appointed as the founding Executive Director/Curator, a two-day a week paid position, which required full seven days a week commitment to open in time.

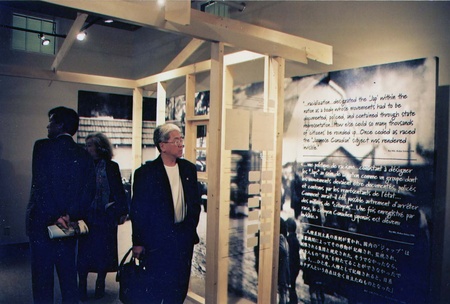

On September 22, 2000, the Japanese Canadian National Museum opened, with the inaugural exhibition, Reshaping Memory, Owning History, Through the Lens of Japanese Canadian Redress, curated by myself and designed by D Jensen & Associates Ltd. The opening ceremony keynote address was offered by a good friend, the late Dr. Michael Ames, Director of UBC’s Museum of Anthropology, who I had consulted throughout the process of developing this museum. My connection to him invited me, prior to the opening of the Museum, to both the national and the provincial Museum Association conferences, at which I was asked to speak to the question why we feel a Japanese Canadian National Museum is necessary, when there are national museums established in Canada.

Unfortunately, I was forced to resign from this position within two years of the opening. Due to a personal conflict initiated by the new President (successor of Frank Kamiya), who refused to understand the difference in roles of board members and staff members, and insisted on interfering regularly with negative and insulting remarks, which did not ease for some two years, even as attempts were made by a few board members to find solutions. I quit the position in January 2002 in the middle of an executive board meeting.

At the time I resigned, the Japanese Canadian National Museum was an independent museum, located at Nikkei Place. A year or so later, when the JCNM and Nikkei National Museum and Heritage Centre boards merged, I was asked by the new board, in offering a public apology, to accept a contract to complete two of the three exhibitions that I had proposed in my five year plan. Production funds for these were already in place before I had left.

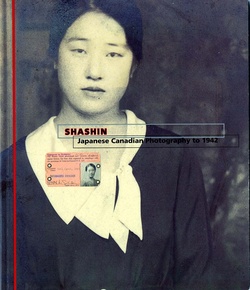

Shashin: Japanese Canadian Studio Photographers to 1942, was an exhibition in partnership with the SSRC-CURA Cultural Property Community Research Collaborative Program and University of Victoria, and was launched successively at each of Royal BC Museum (Victoria) and Japanese Canadian National Museum (Burnaby).

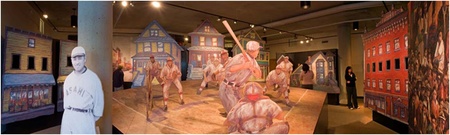

The other, titled Levelling the Playing Field: The Legacy of Vancouver Asahi Baseball Team, opened at Japanese Canadian National Museum and subsequently at Vancouver Museum. A third exhibition I had proposed, which focused on sumie paintings produced in Japan by the renowned BC landscape artist, Takao Tanabe, never materialized. It was cancelled by the Board. However, the exhibition of this theme is, at this time of writing, produced by, and installed at, the Nikkei National Museum.

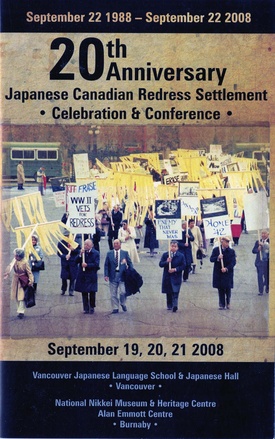

From 2005-2010, I served on the Executive Board of National Association of Japanese Canadians. During my presidency, on the 20th anniversary of Redress (2008), we held a National Celebration (September 19, 20, 21) opening at Vancouver Japanese Language School and Hall and in Burnaby at Nikkei National Museum & Heritage Centre, inviting national participation.

At this event, several workshops were held focusing on history, human rights, immigrant, community health, and intercultural issues. Throughout the weekend, in appointed screening areas, videos both documentary and art by Japanese Canadian artists were screened, also music and dance performances held between workshops.

Also, in Downtown East Side area rooftop, Vancouver-based Kokoro Dance performed a 45 minute site-specific piece. This new work revisits the history that produced Rage in 1987, and The Believer, which was developed as a school program which toured Toronto and Vancouver in 1995. Another performance, was Chikyuu no Stage, a multi-media performance with narration and music by Dr. Norihiko Kuwayama (of Yamagata Prefecture), focused on images of war torn countries (Somalia, Afghanistan, etc.)

Also, during this period, the display, Forced Relocation, installed in the First World War section, at the Canadian War Museum, was brought to the attention of the NAJC board by Japanese Canadian Second World War veterans. Invited to the opening, they noted that there was little or no mention of them in this section. I visited the Museum to find it was not only about omission, but also misrepresentation of our history.

After a couple of meetings with the director and staff, and receiving no satisfaction, only delays, I requested leadership from legal historian, Ann Gomer Sunahara who is an author of The Politics of Racism. The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians During the Second World War (James Lorimer and Company, 1981), and Dr. Roy Miki, poet and writer. He is an author of numerous publications, including Justice in Our Time: The Japanese Canadian Redress Settlement (Talonbooks 1991) co-authored with Cassandra Kobayashi, and Redress: Inside the Japanese Canadian Call for Justice (Raincoast 2004) to produce a position paper addressed to the Government of Canada and to media attention: Taking Responsibility: A Submission to the Canadian Government on the Misrepresentation of Japanese Canadian and Their History (September 2010). It spoke particularly to the issues of misrepresentation in the display, Forced Relocation, at the Canadian War Museum. The Museum made the required changes shortly after with Ms. Sunahara’s direction.

© 2016 Norm Ibuki