Family is important to Yagi, explains his daughter Sakura, because his own was fractured when he was very young. His father died when he was five, leaving his mother to raise Yagi and his four brothers on her own. Before his life was cut short, Yagi’s father, “had a vision of technology taking over the future” of Japan, recalls Yagi. Anticipating the change, he moved from selling fish by bicycle rickshaw to selling electrical lamps for fishing boats. After the family home was burned down during World War II he had to start over from scratch. He began buying up spent car battery cases all over the Kanto region; they were in demand by battery manufacturers who lacked the resources to make new cases.

Yagi recalls traveling to Kyoto with his father on business, where ryokan staff would call him “Bon,” slang for “little boy.” The nickname stuck, so instead of being called by his given name, Shuji, he was ever after known as Bon.

Life changed after his father’s death in 1953, when Yagi was four. In those days, Yagi explains of single mothers, “they thought of you as if you were disabled, a cripple.” As his mother toiled to support her five sons, they were left largely to their own devices. As a successful restaurateur in America, Yagi did not forget his mother’s sacrifices. “He called his mother every night at the same time, until she passed away,” says Saori Kawano.

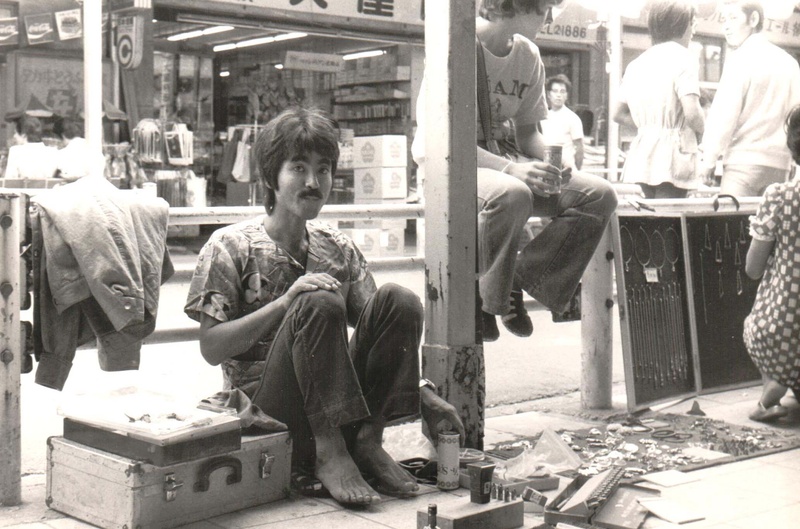

During the Occupation, Yagi became fascinated by the flow of shiny goods entering the country through U.S. miitary bases, and the boom in manufacturing. He spent a summer with a great uncle who was one of Japan’s first successful post-war entrepreneurs, making his fortune in the manufacture of plastic dolls for export to the west. Sitting in his second-floor East Village office, above Cha-An, Yagi pulls one of the ancient dolls from a cluttered shelf; it clearly holds a totemic value for him, a symbol of both America and entrepreneurship.

“One day I want to be like him,” he remembers thinking of his Uncle Daihachi. He also wanted to see “the country that helped Japan transition from bare feet to sandal to shoe.” Companies like Panasonic were launching the post-war “Japanese Economic Miracle,” yet the Japanese themselves, Yagi notes, couldn’t afford those products yet. Realizing that there were “too many potatoes in one barrel,” he decided he had to get out of the country. Mixing metaphors, he recalls saying to himself, “I’ve got to get out of this hakozushi (pressed sushi box).”

Perhaps conveniently, he missed the college entrance exam to Tokyo University that he had planned to take; he was busy helping his best friend Kazuo Wakayama (who went on to become a business partner and fellow restaurant entrepreneur in the East Village) on his milk delivery route early that morning. “I was all sweaty and I asked my older brother what to do,” recalls Yagi. His advice: “Tell our mother you’re going to the U.S. to study English.”

First, Yagi tried to acquire some English-language skills through odd jobs, including putting sheets on beds at the New Otani Hotel, working as a waiter at the Daiichi Hotel in Akasaka, and as a driver at the U.S. Army’s Camp Zama. He also volunteered for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense force for a year.

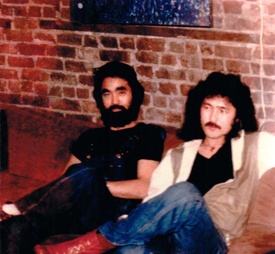

He saved his money and lit out for America in 1968, starting at the bottom as a grave digger, gas station attendant, and then diner dishwasher in Philadelphia, where he worked his way up to short-order cook. The idea of introducing Japanese food to Americans had taken hold, but first he wanted to travel the world. He arrived back in New York from his travels in 1976, launching a vegetable wholesale business in the East Village with his high school friend Wakayama.

It was a rough neighborhood, rife with drug dealers and squatters. Yet Yagi says, “Jewish people started here, and Polish and Ukrainians, and then the Japanese. Everybody was accepted, and we never felt strange.” St. Mark’s Church, nearly at the center of his restaurant galaxy, was for a time the burial site of Commodore Matthew Perry, whose tall ships opened Japan to the west in 1854. Plus, notes Yagi, “East,” or higashi, describes Japan. “That’s why I opened all my restuarants here,” he says simply.

Yagi figured that in Japan, people his age were working 50- or 60-hour work weeks, and if he just worked like them, “one day maybe I’ll be the front runner here—I didn’t hesitate to work long hours.”

He got to know a chef at the Empire Diner, the iconic Tenth Avenue art moderne watering hole that stayed open round the clock and attracted a bohemian crowd. By the early 1980s, Yagi had saved enough money to lure the chef away, and opened his own 24-hour-diner on Second Avenue in the East Village.

Called 103 Second Avenue, it, too, became a hot spot, a regular for artists Keith Haring and Andy Warhol. Haring regularly covered the black walls of the bathroom with graffiti, and Yagi, unaware of it’s potential future value, says, “I used to erase it.” He adds, “My employees were all gay and I sold coffee for seventy-five cents, or a dollar-fifty for unlimited refills. John Belushi would come at midnight and loved Sloppy Joes. Madonna used to come before she was famous, too.”

The stars had no idea that the diner they loved, decorated like an understated Japanese establishment in warm wood floors and wooden tables, was run by a Japanese man. Foreshadowing his continued relative anonymity, Yagi says, “I didn’t want anybody to know.”

His stealth “Japanese diner” gave way to his first real Japanese restaurant in 1984, Hasaki, a sushi restaurant on East 9th Street named after the small town in Chiba where his father was born. The underground sake bar Decibel followed in 1993, and Sakagura in 1996. Yagi’s empire building was underway.

His daughter Sakura attributes Yagi’s success to his insatiable curiosity and appetite for work. “As a self-employed person, he’s always on it,” she observes. “There’s never a moment he’s off, and he doesn’t hesitate when there’s a problem to be solved.” In addition to overseeing his 13 restaurants, he owns and manages several apartment buildings, is the New York agent for Toto, and at one time was also president of a beer exporting company.

When Yagi decides on a new restaurant concept, his daughter notes, he travels through Japan doing research, decides what to focus on, and finds people to implement his vision. And, she adds, “He’s never afraid to ask questions,” a trait that was embarrassing to her when she was younger, but which she has come to appreciate.

At 67, Yagi shows no sign of slowing down. He plans to expand the business, says Sakura, likely in Japan. But he’s also turned his thoughts to the humanitarian concerns that have marked his career in New York. As chance would have it, he was downtown for both the 1993 below-ground bombing of the World Trade Center and for the September 11, 2001 attack. In 1993 he was on the 87th floor of the World Trade Center, visiting the Hokkaido Takushosku Bank when the underground bomb was detonated. On 9/11, he was with Sakura at the immigration offices nearby the trade center. He took his daughter’s hand and walked her back to the safety of the East Village through Chinatown. Shaken, he took the attacks as a wake-up call to perform an act of Zen self-discipline to honor the dead. As an end-of-year symbolic cleansing, he decided to give up something he loved—sake—and did not imbibe it again for 10 years, until the day his son turned 21.

He was one of several community leaders who started New York City’s akimatsuri fall festival in 1990, and is currently leading the effort to repair a statue of Shinran Shonin that surived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and now stands in front of the New York Buddhist Church. Drawing his roster of restaurants into his charitable activities, he hosts a yearly dinner for Nikkei seniors at Shabu Tatsu.

Through a lifetime of bold entrepreneurialism and constant activity, Yagi has created a microcosm of Japan within New York City, introducing the food-scapes of everyday Tokyo to locals more familiar with pizza and bagels. For his “last achievement,” Yagi has his sights set on importing a more spiritual, or cultural Japanese asset to New York: He wants to start a non-profit devoted to the Japanese principle of ichinichi ichizen, or “one good act per day.” Since he shows no sign of slowing down, it’s unclear when he will launch the non-profit, but Yagi envisions it as yet another way of making the city a better place.

“It’s very Japanese, and something I grew up with,” he says. “It’s not meditating,” he explains, “but improving things, through even the smallest of acts.”

© 2015 Nancy Matsumoto