Sus Kaminaka was a zoot suiter: one of the many young people in 1940s America who embraced a distinctive, working-class urban aesthetic characterized by flamboyant fashions and irreverent comportment. Kaminaka and other hipsters sported pompadours and ducktail haircuts, “drapes” consisting of broad-shouldered, long fingertip coats tapered at the ankles, pleated pegged pants, wide-brimmed hats, and watch fobs. They also loved to party. Jazz, jitterbugging, lindy hopping, drinking, casual sex, and “cool” were just as integral to the lives of zoot suiters as their characteristic dress.

Sus Kaminaka was also a Nisei: a second-generation American born to immigrant Japanese parents and raised in the farmlands of California’s Sacramento Delta region. Planning to follow in his father’s footsteps, Kaminaka enrolled at a local agricultural college to study truck crops.

But President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, signed on February 19, 1942 and authorizing the secretary of war to “prescribe military areas… from which any or all persons may be excluded” completely upended his ambitions. Ostensibly region- and race-neutral, the order targeted Pacific Coast Japanese Americans. Forced to leave school, home, and community, he soon found himself in the Stockton Assembly Center, one of the 16 temporary way stations for the 120,000 Nikkei (persons of Japanese ancestry) en route to longer-term concentration camps.

On incarceration, Kaminaka’s worldview changed entirely. Previously intent on earning his college degree, a goal he now considered hopeless, he dropped out of his center’s adult education program. Once “proud of living in the best country in the world,” Kaminaka abandoned the idea of registering for the franchise. “I don’t think I was too interested in voting anyway because I didn’t know what it was all about and my vote didn’t mean a thing,” he shrugged. Deciding that hard work was an exercise in futility, he instead “concentrated on having fun like [he] saw the other kids doing.”

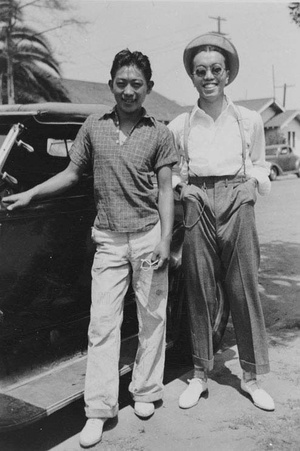

Mack Hori and George Shibata posing on Second Street next to a friend’s car in 1937. Gift of George Fujino, Japanese American National Museum [2000.418.10]

Before the war, he used to regard Nisei girls as “something sacred” and “never had any dirty thoughts [about] them.” But in Stockton, he shed his “nice boy” reputation. He signed up with an eight-member “gang,” and spent his days and nights chasing young women and going to camp dances. It was during this time that he also acquired his first zoot suit.

After transferring from Stockton to the Rohwer, Arkansas concentration camp, Kaminaka joined a posse known as the Esquires. For entertainment, they devoured stolen food, drank, played poker, and held nightly bull sessions. “All we talked about was girls and we got to do more and more of this…. We would find out who were the most popular girls in camp and then go after them.” Their modus operandi emerged as a source of contention among Rohwer’s social factions. Fisticuffs often broke out at Nisei dances as young men battled to claim the young women of their choosing.

The Rohwer situation was not usual. Conflicts between “rowdies” and other prisoners interrupted the daily routines of several, if not all, the camps. At the Gila River camp in Arizona, for instance, the editors of the center’s newspaper complained that zoot suiters had swiped all the chains from the laundry sinks to use as watch chains. Fighting became frequent enough that at least one anthropologist who observed life at the Poston camp dubbed the escalating tensions “zoot suit warfare.”

In popular memory zoot suiters are often associated with African Americans and Chicanos during World War II. But many Nikkei also participated in this cultural movement. While it is not possible to determine the exact numbers of Japanese American zoot suiters, the available historical evidence suggests that they were a visible presence.

Some Nisei started “zooting” well before camp. In his hometown of Los Angeles, all of Lester Kimura’s friends happened to be Chicano, and they influenced his fashion sense: “I learned how to dress from the Mexican kids because they really knew how to be classy,” he explained. “They had ‘drapes’ way before the Nisei heard of such things.”

The big-city Nisei who carried this look into the camps exposed young people hailing from rural areas—such as Kaminaka—to zoot suit style. Spotting a lucrative opportunity, Kimura ran a brisk business at the Santa Anita Assembly Center draping pants for the newly-initiated.

So the internment experience itself was an incubator for Nikkei zoot suit culture. Japanese Americans even invented their own slang for Nisei zoot suiters. One was “pachuke,” a Japanese version of the Spanish word “pachuco”/“pachuca.” The other was “yogore,” a derivation of the Japanese verb yogoreru (to get dirty). Sociologist Shotero Frank Miyamoto, a contemporary observer of Japanese America, explained that “yogore” referred to individuals who were “shiftless, transient, constantly drinking and gambling, hanging around pool halls, always picking fights, visiting prostitutes, or attempting to engage in illicit sex relations.”

Yogore posed a serious problem to the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the federal body charged with administrating internment.

From the WRA’s point of view, zoot suiters endangered the very future of the entire Japanese American population. The federal government planned to scatter (or “resettle”) Japanese Americans around the country so that they might “assimilate” into the white middle class instead of returning to their West Coast farms and Little Tokyos. Pachuke troubled this vision for solving the “Japanese Problem” because they spurned polite standards of decorum. Their brashness loudly advertised their differences from the white middle-class. It also suggested an explicit kinship with working-class black and brown folk—the very opposite of the message that the WRA wanted to send to mainstream America.

Even worse, the zoot suit itself signaled an open defiance of the nation’s war effort. The War Production Board had banned the sale of zoot suits as a means to ration fabric. So wearing a zoot suit could be read as an unpatriotic act. The eruption of Los Angeles Zoot Suit Riots in June 1943—when thousands of white soldiers and civilians violently attacked Mexican Americans and other zoot suiters of color—drove home this point.

Thus pachuke let loose from the camps might place Nikkei under further suspicion of disloyalty. No wonder, then, that the Manzanar camp’s Free Press newspaper editors beseeched its readers: “Leave your zoot suits behind. And above all, be an ambassador of goodwill for the sake of the Japanese in America.”

* This article was originally published on Nikkei Chicago on January 25, 2014.

© 2014 Ellen D. Wu