My dad Minoru Yasui was always, or almost always my hero. But of course that was not true for everyone, nor at all times.

When he initiated his test case in 1942, he was not considered a hero. The press labeled him a treacherous Jap spy, and the National Secretary of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) called him “a self-serving martyr … seeking headlines.” In 1944, when he visited the Heart Mountain draft resisters to try to persuade them to withdraw their cases, they felt betrayed by the man who purposely defied the military curfew, but opposed their way of challenging the injustice of the Relocation Camps. In the 1960s when he was Director of the Denver Commission on Community Relations, racial tensions were running high and the Chicano Crusade for Justice clamored for his dismissal for what they considered “whitewashing” a police-brutality case involving a Latino youth. During the redress movement of the 1970s and ’80s, there were those who disliked his style and approach because he was highly opinionated, forceful and, as he put it, ornery.

Min Yasui was, for better or worse, a public figure and he was not afraid to take a stand, even if it was not popular.

So, what can I tell you about him, not as a hero or a public figure, but as a person, a father?

Well, he was a great dad—loving, attentive, and generous.

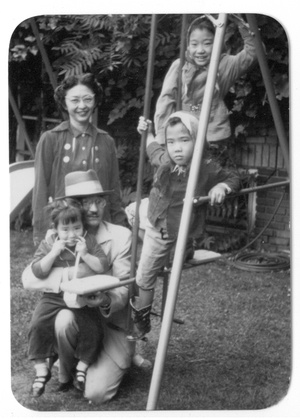

I’ve read stories by children of activists, who felt neglected and overshadowed by the importance of their parents’ causes, but I never felt that way. Even though my dad went to community meetings nearly every weeknight and weekend (my sisters and I thought that all fathers did that), he and my mom always made efforts to include my sisters and me in their activities.

In the early days when my mom was my dad’s secretary, she took us downtown to the office after school and on weekends. He was a self-employed attorney, so there was no problem for us to hang out in his office, which was a proverbial hole-in-the-wall in the heart of downtown Denver’s “Skid Row.” His clients were mostly Japanese American, impoverished by their wartime experiences, and other low-income minorities. His was a one-man legal aid office, before there was such a thing.

For that reason, my dad often accepted merchandise instead of cash for his services—we kids loved going to the Japanese store around the corner from the office because they gave us comic books and trinkets “on credit,” and we ate next-door at the Akebono restaurant for “free.”

One year a Nisei farmer gave us a live turkey that we kept in our backyard. It was a big, noisy bird and it tried to bite us when we gave it food—we were all afraid of it. Even though it wasn’t exactly a pet, when November rolled around, we just couldn’t kill it for Thanksgiving dinner. So we gave it back, since unlike city people, farmers aren’t queasy about slaughtering livestock. What a deal! Not only did my dad not get paid, we fattened up that mean old turkey for months and another family ate it.

Growing up, we kids endured interminable JACL events, practiced judo at the Denver Dojo, enjoyed holiday parties at the VFW Cathay Post, and Japanese samurai movies at the Tri-State Buddhist Church, organizations for which our dad did legal and organizing work. We kids also liked helping with the AJA News, which our dad wrote, edited, and laid out. AJA stood for “Americans of Japanese Ancestry,” and the newsletter had over 100 subscribers (I don’t know if they were all paying or not—probably not). My sisters and I ran the mimeograph and addressograph machines. This was before photocopiers, and long before computers! We folded and sorted each edition by postal code on our living room floor, then took them to the post office in separate packages tied up with string.

My dad was also a Boy Scout leader. I think that was an antidote to his all-female family (wife and three girls) and an essentially sedentary job. He loved the outdoors, a love that arose from his own childhood growing up in Hood River near the Columbia River in Oregon. In the 1950s and ’60s, he took his rag-tag multiracial Boy Scout “Troop 38” camping in the mountains west of Denver once a month, all year round. My sisters and I got to tag along in the summer, and during those long, sunny days, he sometimes took us on fishing trips. I never could push a live worm through a hook, but I liked sitting with my dad at the side of a stream, not talking (he said that scared the fish), just enjoying the natural tranquility of the beautiful Rocky Mountains.

Summer was also family trip time. We all piled into our station wagon and drove to the West Coast, to the Midwest, to the East Coast. We had stickers on the back window of our car from over 40 states. I later learned that before I was born and when I was a baby, my dad was lobbying for and then receiving and delivering documents related to the Evacuation Claims Act of 1948, which he and JACL helped to push through Congress. Likewise he travelled across the country lobbying for the Walter-McCarran act of 1952, which enabled the Issei to become naturalized citizens.

We continued that family tradition of taking summer car trips until the 1960s. My dad was always busy doing what we now call “networking”—weaving and maintaining a social fabric among Japanese Americans who after the war were dispersed all across the American landscape. In between sight-seeing stops, my dad attended meetings and gave speeches—in community centers, churches, barns, where ever people would gather and listen. He was an old-style orator who mesmerized crowds with his vivid stories and grandiose delivery—that’s how I heard many of the stories that have become a part of our family lore.

So, in our home, the subject of the Relocation Camps was not “taboo,” not cloaked in silence or shame. In fact, when I was a child, I thought that the camp where my mom was interned, Granada, was like the summer camp that I attended, because she often talked about her “friends from camp” in wistful tones that made me think that it had been much more fun than raising a family on shoestring.

My dad, on the other hand, liked telling how he initiated his test case: walking the streets of Portland for hours after the 8 p.m. curfew proclaimed by General DeWitt, trying to get arrested, but to no avail. He would animatedly recount how he marched into the police headquarters with the proclamation and his birth certificate in hand, insisting that it was the duty of the police to arrest him. We always laughed at the punch line, when the officer said “Run along home, son, or you’re going to get into trouble.”

This anecdote has made its way into many accounts about my dad’s arrest, and I always enjoy reading it because I remember very clearly his intonation and expression when he told it. He was aware of his tendency to be somewhat bombastic and was not above poking a little fun at himself. Also, I think it was important to him to remind people that not all authorities were prejudiced—some, like that patronizing but well-meaning cop, were even somewhat sympathetic.

Another family story, about my grandma, Shidzuyo Yasui, impressed me deeply.

In 1942, she was heading the household alone since my grandfather had been taken away in the first sweep by the FBI. My dad got arrested on a Friday night, and over the weekend there were photos of him on the front page of the newspaper with the blazing headline “JAP SPY ARRESTED.” On Monday, he phoned his mother in Hood River and apologized for causing her so much worry. She replied:

“Shimpai dokoro ka, Susumeru yo! Ganbatte!”

(I’m not worried. I support you! Persevere!)

This, from a woman whose husband had been disappeared and, in his absence and without a word of English, she was managing the family farm and store in the face of great uncertainties and hostility. She didn’t scold or complain about her son’s arrest, but encouraged him! I think that tells volumes about where Min Yasui got his courage and the will to see his case through to the bitter end.

Perhaps my dad was not as good a “provider” as some fathers—I now know that my mom struggled mightily to pay the bills, to feed and clothe us (as the youngest, I always had to wear hand-me-downs, which I hated). But making money was never an important value in our home, though I imagine that my mom often wished it had a little higher priority. My dad was so occupied with pro-bono JACL work and helping to organize community organizations such as the Black Urban League, the Latin American Research and Service Agency (LARASA), and Denver Native Americans United, that he left all the finances to my mom, who scrimped and saved and stretched the paltry fees that he charged to his low-income clients (when he charged).

In the mid 1960s, my dad finally gave up his very un-lucrative private practice of law and took a job with the City of Denver to direct the Commission on Community Relations. When my oldest sister entered high school, he and my mom decided that he had to make more money, or at least have a regular income so that they could send her to college, and my other sister and me in subsequent years. Education, as opposed to money, was a big deal.

So, of course I did go to college, and it was then that I learned more about my dad’s wartime experiences by interviewing him for a writing class, and I started working on a play about his legal case that I did not finish until after his death.

In my 20s, I was into redefining identities and bucking the system, which sometimes put me at odds with my dad—for example, he was not sympathetic, as I was, to Marxist theory, the anti-war movement, and radical protest tactics; he was occupied with practical issues related to redress at that time. But in general, our relationship was very close. I visited home nearly every weekend when I went to the University of Colorado, and he frequently wrote letters when I was at school in Los Angeles and in Madison, Wisconsin. He was an extremely prolific letter-writer and organized his life by typing up multi-page agendas and itineraries detailing where he would be every day, with whom, and for what cause. These voluminous documents were especially useful when he was travelling—which he did, very extensively, for redress in the 1970s and ’80s.

When I was attending the University of Southern California, I accompanied him on a Manzanar Pilgrimage, and I remember criticizing his speech as “bombastic” (I later discovered why JACL, which he was representing, was not very welcome there). At the University of Wisconsin, he gave a talk about redress to the Asian Student Union, which I helped to organize. At first I was a little embarrassed by his old-fashioned oratorical style, how the hip young Asians rolled their eyes and snickered, but little by little they grew silent and less restive until the end when he rousingly proclaimed “… this shall never happen again!” and they stood up to give him a standing ovation.

I learned about the Heart Mountain draft resisters after my dad’s death, so I was never was able to ask him about his role in that painful episode of our history. Several years ago at a conference, I found myself in the awkward position of trying to represent his position, with which I did not entirely agree. In my play, I created a character, a boyhood friend who becomes a draft resister, in order to try to address the emotional and moral complexities that the young Nisei faced during that incredibly difficult time.

I’ve only recently read the Lim Report (I’ve been in Mexico for the past 20 years, not connected with the Nikkei community until I retired and attended the 2013 JANM conference in Seattle). That document reveals an entirely different view of the JACL than what I grew up with. Throughout his life, I thought of my dad as “Mr. JACL”—he was a deeply committed, active, and outspoken member of that organization, in spite of the stunning disavowal issued by the national headquarters in 1943 and general antagonism to his case during the war, including breaking up a grass-roots support group in Minidoka where he had been interned.

Since learning about those insults and injuries perpetrated against him by the JACL, it never ceases to amaze me that my dad not only forgave those JACLers who opposed him during the war, but continued to work with them on issues that they did agree upon, such as the draft resisters and later, redress. He was not, like some people believe, wedded to the JACL “party line.” He stood by his own principles even when his allies or would-be allies disagreed, and worked toward convincing them to understand what he believed was right and for the common good. He was a man of great personal integrity and of sufficient moral stature that could forgive (and admit) errors, listen to the arguments and opinions of others, and compromise on strategy when necessary, but never on principles.

After he retired from his job with the City of Denver in 1983, my dad went into action full-blast as Director of the JACL National Committee on Redress. He wrote letters to the President and his cabinet, members of Congress, friends and colleagues of influential politicians of all stripes; he made thousands of phone calls, hundreds of speeches, gave interviews, and attended meetings every day, often several per day. He criss-crossed the country, travelling literally thousands of miles, a virtual lobbying machine set on high drive because he knew his time was limited—and that of the Issei even more so. He died in the fall of 1986 at the age of 70.

I’m sorry my dad didn’t live to see the signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, but I believe that for him, the final results were never as important as the process, the work of carrying on the work—as the coram nobis attorneys have continued to do with various amicus briefs over the years; and as community groups and organizations like the Japanese American National Museum have done with conferences and other activities and events that keep alive the memory of our shared past as well as orient us toward a shared future.

My dad experienced so many “failures” that might have discouraged a person with less faith in and commitment to justice—the dismissal in 1943 of his original case; his unsuccessful bid for National JACL president in the ’80s, on a platform focusing all the organizations’ resources into redress; the unsatisfactory resolution of his coram nobis case, without an evidentiary hearing. But he never wavered, he did persevere, as his mother and father taught him.

I’d like to end this essay with an affirmation of what my dad said to me when I was a child, a teenager, and adult; what he told me that his father told him:

“We are born in this world for a purpose, and that purpose is to make it a better place.”

This is, of course, not only an altruistic motto, but in its generality, also deeply generous. My dad was not demanding about what we, his daughters, or anyone else did to fulfill their purposes. None of us three girls became lawyers, much less public figures. He never imposed his opinions upon us. Even when I was a know-it-all university student, he respected my right to think differently (but he did try to “talk sense into me”). My sisters and cousins and I, and many others whom he mentored have in fact “followed” not so much in his exact footsteps, but the path that he forged, each doing our best to make the world a better place, each in our own way, true to our own convictions and passions, our own life experiences.

* * * * *

Holly Yasui is currently working on a tribute to Min Yasui to take place in 2016, the centennial of her father’s birth. She would greatly appreciate help from any readers who have materials, especially recordings (audio or film/video) of Minoru Yasui that they might be willing to loan for this project. Please contact her through Discover Nikkei at Editor@DiscoverNikkei.org.

* Holly Yasui was a panelist for the “Hirabayashi, Korematsu, and Yasui: Family Perspectives” session during JANM’s National Conference, Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity in Seattle, Washington.

© 2013 Holly Yasui