“Don’t sweep the house at night or you’ll become poor” or “if you cut your nails at night, the devil will come for you.” Even more prophetic, “you are going to cry…” which my oba always said when she saw the cat washing herself. I heard these and other sayings while growing up. When my oba left us, we didn’t hear such things as often, but there are a few (in addition to many other traditions and beliefs) that are part of our memory; if nothing else, they are reminders of my oba. As they say, old traditions hang around for a long time. It’s just as difficult to forget the older beliefs that my oba brought from Okinawa.

My oba arrived in Peru in 1918 from the town of Yonabaru, which is to the south of Okinawa. She came with my oji and together they crossed the Pacific Ocean and arrived in Peru, bringing with them not only their hopes and dreams for a better future but also their beliefs and traditions.

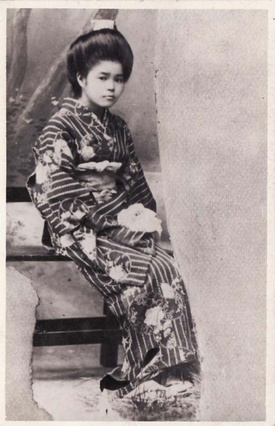

A photo of my oba dressed in a kimono when she was eighteen years old (this photo is an enlargement of the original, which is cut into two pieces).

And that’s how I was grew up, surrounded by Japanese and Okinawan traditions and beliefs that I learned from my oba and my mom. Although much time has passed since then, I still put them into practice. For example, I have a butsudan in the house even though we are Catholics, and I ring in the New Year with Japanese food. Other examples include, perhaps, mixing Japanese words such as okane or gomen, among others, when talking with other Nikkei who also speak Spanish. We shouldn’t forget the old saying that our oji and oba always told us: if we have a dream with unchi, we ought to be happy because it means that we are going to receive okane.

Truth be told, there are several traditions that we still practice at home, although when I was a kid, I didn’t always share these traditions with my friends because I figured that they wouldn’t understand them (since I was the only Nikkei in a classroom of 30 girls). My oba always said: “Dojin at school; Nihonjin at home,” which was her way of distinguishing what went on at home (Japanese traditions) and what went on outside the home (Peruvian ways). While at home she taught me how to distinguish one person from another (this person is dojin, that person is nihonjin, the other is ainoko, etc.), in school I was taught about equality. My friends’ parents would scare them with stories of the boogeyman whenever they behaved badly; my family, on the other hand, would scare me with stories of the obake and other stories such as “whistling at night only attracts the obake,” or “don’t sit on the table or the oshin will grow.” At times, I didn’t really know if this stuff was true or not, or if my oba was just telling me only to make sure that I listened to her. Happily, this “double identity” (between Japanese and Peruvian cultures) never turned into ‘culture shock’ for me; truth be told, it was harmonious coexistence (is it possible that Nikkei identity sprang from this?)

In addition to these traditions and beliefs, there are other things that are lost over time, things that we rarely practice anymore at home. They remain part of who I am, of course; I’m not really thinking of my oba’s traditions, but rather memories of my childhood with my oba.

My oba taught my mom a tradition that I used to do each time I put on new clothes. I remember that when we went out, my mom grabbed me while I was dressing and carried me to one of the walls in our home. With a piece of my clothing in her hands, she would tap the wall, saying in a soft voice: chino miku duu gan jyuuku, which translates as “new clothes, new clothes, a strong body.” After saying the words and tapping the wall, my mom would tell me that I would always have new clothes.

A photo of me when I was five years old. In the kindergarten where I studied, the school organized a costume party where my friends dressed up as police officers, princesses, and clowns. I, on the other hand, wore a kimono. It was the first and last time that I ever wore one.

I never asked her if that really worked, but recalling how old I was (five or seven years of age), I ended up believing my elders. In fact, I always believed whatever my mom and oba told me. If they told me, for example, that “nothing bad was going to happen” when I was afraid (going to school for the first time, not wanting to sleep alone, or being afraid that the obake was under my bed), they were always right. Nothing ever happened to me, as my childhood fears magically vanished. And the moms—in my case, my mom and my oba—always knew how to make us feel safe and secure. While the rest of my friends received their grandparents’ blessings, my oba always protected us before we would go out. In her own way, of course, or perhaps better said, in the Okinawan way.

Everytime we would go out, my oba would wet the tip of her finger with saliva and then touch our foreheads. She was protecting us from anything bad that might happen to us. If, for example, I was running around the house and fell down and started to cry, my oba would repeat the rhyme “mabuyá, mabuyá, utikumisoré, mabuyá, mabuyá utikumisoré, and, simultaneously patting my back, she would calm me down.

Not everything was done, of course, to obtain something new or to avoid something bad. I also recall one of my oba’s beliefs—one that we still practice today—which remains a family tradition. She used to make us clear the table before we were finished eating, and not because she feared we would get too lazy afterward; rather, she didn’t want us to eat so much at dinnertime. My oba would also say that if during the meal there was a tremor or an earthquake, we should eat seven more times and then good luck would come our way. But who could eat so much? By bringing the plates to the sink before we finished the meal, we would avoid indigestion. Today, we continue the practice of bringing our plates to the kitchen before we have finished eating, not so much because we believe that earthquakes bring luck, but rather because it has simply become a framily tradition.

In fact, there are many beliefs and traditions that my oba brought over from Okinawa, some of which are difficult to forget. And not because we continue to practice them at home but—just like photographs—they are the only memories that I have of my oba.

© 2013 Milagros Tsukayama Shinzato