One Saturday afternoon, I was driving toward San Pedro. At a fork just before the end of the Harbor Freeway, I headed toward the green Vincent Thomas Bridge. The bridge, where a famous film director jumped to his death last summer, is quite high above the water and offers a view of the Port of Los Angeles below. Terminal Island spreads out to the right as I head toward the road. Before the war, this was a fishing village where 3,000 first and second generation Japanese Americans lived.

When the war began, they were forcibly sent to internment camps. Now, the only remnant is a monument erected by the sea in 2002. The photographs on the monument show the elementary school, shrine, streetscape, and fishermen of the past. Where did they come from, and what are their descendants doing now? To find out, I went to meet Minoru Fujiuchi, one of the living witnesses to Terminal Island, who lives in the suburbs of Los Angeles.

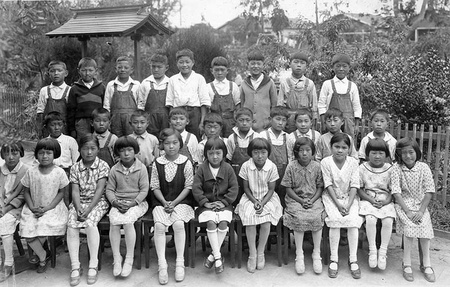

Almost all the elementary school students are second generation Japanese.

Fujiuchi-san still vividly remembers the scenery of Terminal Island, where he lived until he was seven years old. He is holding a Japanese plate bearing the name of his family's main store in Wakayama.

Fujiuchi was born in Terminal Island in 1929 and grew up in San Pedro, across the bay. His father and a partner ran a large vegetable business in the market.

His father, who was born in Ezumi, Susami-cho, Nishimuro-gun, Wakayama Prefecture, was the 21st generation owner of a local fishing business. He went to America in 1906, relying on his brother-in-law (his sister's husband) who ran a restaurant in Bellingham, Washington, near the Canadian border. His brother-in-law made a success of the 10-cent meal restaurant, which offered stew, bread, coffee, and pie, and sponsored many Wakayama fishermen to come to America.

Fujiuchi's father traveled back and forth between Japan and the US several times, before finally crossing the ocean again with his wife in 1921. Around that time, his brother-in-law sold the restaurant and moved to Terminal Island in the Port of Long Beach, south of Los Angeles. At the request of the cannery, he returned to his original occupation as a fisherman in Wakayama. At that time, many fishermen left Bellingham and joined his brother-in-law.

"The cannery on Terminal Island needed skilled Japanese fishermen. They canned the tuna, sardines, mackerel, and white tuna (abacoa) that the fishermen caught. The company provided housing for the fishermen and rented it out cheaply. The houses were designed to accommodate two generations, but I remember that my uncle (my father's brother-in-law), who was a leader among the fishermen, occupied the whole house even though he and his wife had only one child. It was spacious, with a living room, dining room, kitchen, and bedroom." (Fujiuchi)

After spending a few months in Japan caring for her sick grandmother, Fujiuchi's family returned to the United States and stayed with her father's brother-in-law for about a year. Fujiuchi was six years old at the time.

"I went to an elementary school on Terminal Island. It was called the Walliser School. The teachers were white, but almost all the children were Japanese, the children of fishermen. Fishermen's language is rough, so the children naturally imitated their parents' language and used rough Japanese. I call it terminal dialect. Also, because all my classmates at the time were Japanese, we didn't speak to each other in English. As a result, I found myself in a situation where I could read, write and do arithmetic in English, but I couldn't speak it."

Everything was available on the island.

The family moved to San Pedro, on the opposite bank of the river. Fujiuchi was the only one of her siblings to stay with her uncle and continued attending Walliser School for a while, but eventually transferred to an elementary school in San Pedro. "Then, because I couldn't converse in English, I had to start over from first grade, even though I was supposed to be in second grade. After that, my life naturally became centered around English."

Although the family moved outside Terminal Island, Fujiuchi frequently returned to the island to visit his uncle.

"With over 3,000 Japanese living on the island, you could get everything you needed. Almost all daily necessities and food could be purchased at the stores on Terminal Island, and there was also a restaurant. A store called Kurata had opened a branch on the island, so you could buy refrigerators and other home appliances. The fishermen didn't even have cars because they had no need to go out. They usually went to Little Tokyo for trips, and to get there they would take a boat to San Pedro on the opposite shore and then catch a train from there. The fishermen who went to Little Tokyo apparently spent the money they earned from fishing wisely. The owner of Umenoya (a confectionery company that makes rice crackers and other products) said that they were able to get through the Great Depression because the fishermen of Terminal Island bought a lot of their goods."

In addition to a school, a fishing association, and shops, the island also had a shrine and a Baptist mission, as well as a dojo for judo and kendo, where many children worked up a sweat.

However, after the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, all Japanese fishermen and their children were sent to internment camps, and all remaining facilities were removed, completely changing the appearance of Terminal Island.

© 2013 Keiko Fukuda