One day, a friend showed me a photo he had taken on his digital camera. A torii gate stood with the sunlight of the seaside as its backdrop. "Where do you think this is? Terminal Island between San Pedro and Long Beach (in the suburbs of Los Angeles). Apparently there used to be a Japanese town there. Apparently this torii gate is a remnant of that."

I have heard of Terminal Island. Before the war, it was a town for fishermen who had immigrated from Wakayama Prefecture, and apparently even had an elementary school, but now it is no longer a place where people, not just Japanese people, live.

Currently, most of the Japanese and Japanese people living in the Los Angeles area seem to be concentrated in the South Bay area, where Gardena and Torrance are located, and in Orange County to the south, around Irvine and Costa Mesa. However, this has not always been the case, and is also the result of an influx of Japanese people from other cities.

A photo that my friend showed me sparked my desire to research "towns where Nikkei lived." These include places like Terminal Island, where many Japanese people once lived but are now deserted, and places where Japanese people still live but have become towns for the elderly as generations have changed. In the next few posts, I would like to write about the past and present of "towns that thrived as centers of Japanese life."

Crenshaw Square bustling with the Bon Odori dance

I have never been to Terminal Island. I have never had a chance to go there because it is only accessible by crossing a bridge from the port of Long Beach. However, there is one place in the "town where Nikkei lived" that I have visited several times before. It is the area in the southwest, known in English as the Crenshaw District.

Crenshaw Square used to be lined with Japanese stores. California Bank and Trust (right), formerly the Sumitomo Bank, and the oriental-style signboard of the square are vestiges of the Japanese history.

If you head north on Crenshaw Boulevard from the South Bay area, before you hit the 10 Freeway, there is an area where hospitals, shopping malls, and large churches are concentrated. The people walking along the road are mostly African-American or Latino. However, when I visited the homes of Japanese people for interviews, their addresses were in this area more than once or twice. They all said, "There used to be a lot of Japanese and Japanese people living here, but now there are very few of them." Indeed, looking around, there are no Japanese businesses to be found. However, there is something reminiscent of Japan, such as the structure of the surrounding houses and the garden trees, which are somewhat Japanese.

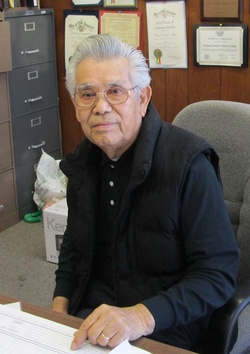

We spoke to Kunio Shiba, president of the Seinan Senior Center, about the Seinan area. Shiba was born in 1929 and is a second-generation Japanese who came back to America. He returned to his hometown from Shizuoka Prefecture at the age of 20.

"I could do all my errands here without having to go to Little Tokyo," said Shiba, president of the Southwest Senior Center and a resident of the area for 60 years.

"A year later, in 1950, I got married and moved to a new house nearby," Shiba said, reflecting on his 60 years in the Southwestern area, sitting in the center's offices about two blocks east of Crenshaw Boulevard.

"The area was most lively when Crenshaw Square (a shopping mall that still stands today) was built. There were many Japanese-run stores, and Bon Odori festivals were held in the large parking lot. During festivals, the area was packed with Japanese people. At that time, this area was the most prosperous of any other Japanese community. You could do all your necessities within Seinan without having to go to Little Tokyo. There was also Enbun Market (a Japanese supermarket) and a bowling alley run by a Japanese person. The building that housed the bowling alley is now a Starbucks, but the exterior of the bowling alley remains."

In addition, the Southwestern area was also home to Daiichi Gakuen, a Japanese language school for the education of Japanese-American children. Shiba, who had three children there, went on to serve as chairman of the Japanese Language School Cooperative System, which oversees Japanese language schools.

"Every day after finishing their English classes, the children would go straight to Daiichi Gakuen to study Japanese. At one time there were about 700 students. As the number of students increased, the school building was expanded. However, Daiichi Gakuen closed down a few years ago."

Crenshaw Square was crowded with people during the Bon Odori festival in summer, Daiichi Gakuen had a shortage of classrooms for the children studying Japanese, and the bowling alley was a place where Japanese-American teenagers gathered on weekends...that was the Southwestern District half a century ago. What on earth happened in Southwestern District? Why didn't Japanese and Japanese-Americans try to stay here? In response to this question, Shiba began to speak slowly.

© 2013 Keiko Fukuda