Drug addict: Medical advances make me weep for old age

My wife has passed away and I know the cold of the winter wind

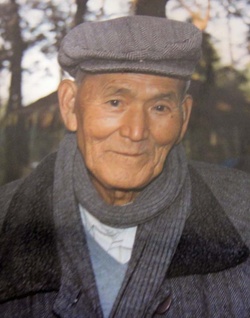

This haiku was written by my father-in-law, Masaharu Uemura, in the solitude of his later years. For many years, he composed waka poems as a hobby, and submitted them to the poetry and yanagi columns of the San Paulo and Nikkei newspapers. Every time I read them, I was struck by how they seemed to capture my father-in-law's heart and the atmosphere he was in.

My father-in-law was born in Wakayama Prefecture and was the second son of the Uemura family, which had three boys and four girls. At the age of 10, he came to Brazil with his family on the Santos Maru in 1928. He seems to have been the hardest worker among his siblings. He worked in farmland in Vera Cruz, deep in the state of São Paulo, and after much hard work, he became independent and started a shop in the city of Dracena.

He and his wife Shizuko had two sons and four daughters, and gave the highest education to six of his children (three in medical school, two in humanities, and one in engineering). My father-in-law never attended a formal school after dropping out of elementary school in the fourth grade to come to Brazil, but he had mastered reading and writing Japanese almost entirely by himself. He was a symbol of the true "Japonais Garantido" who hated crooked things.

He had undergone major intestinal surgery at the age of 60, and had been careful about his health ever since. His wife, Shizuko, suffered from cerebral anemia at the age of 75, and passed away two years later in July 1997, surrounded by her family. At the time, his two sons were still single, but all four of his daughters were married and they had nine grandchildren.

After my father-in-law lost his wife, he decided to live in a nursing home called Ikoi no Sono so as not to cause trouble for his family, and he was cared for there for four years until he passed away in May 2001.

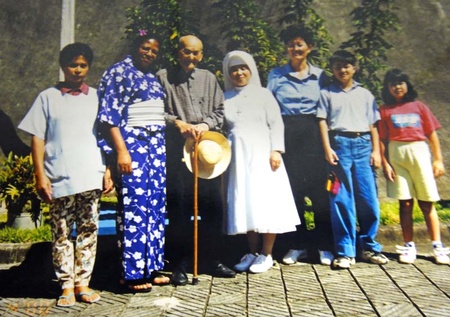

While my father-in-law was in the care of Ikoi-no-en, our family visited him often, and we were able to learn a lot about what life was like there.

The attentive and kind consideration of the Caritas nuns and the results of the charity volunteers who support the facility from behind the scenes can be seen in the small details of daily life. However, there are hardly any visitors, and many elderly people live lonely lives there. Some are jealous of the other residents and play pranks and are mean like children. Some complain that "pee has spilled and the toilet is dirty." On the other hand, we often see happy scenes of like-minded people sharing snacks given by visiting families. Everyone at Ikoi-no-en has been so kind to us, and our family is truly grateful.

My father-in-law was originally a Shingon Buddhist, but after entering Ikinoen, perhaps for some reason, he became a devout Catholic, was baptized with the name Johannes, and was truly happy.

Even after my father-in-law entered Ikoi-no-sono, he continued to compose poetry. The following is what he wrote at Ikoi-no-sono.

In the hallway where dinner has already been served, an old woman sings a child's song.

The nuns dance with joy at the Junina Festival

This is a poem that my father-in-law wrote about a refined woman who played the koto and whom he met at Ikoi-no-en. The woman had some problems with her left arm and used a wheelchair. My father-in-law and I seemed to get along very well, and we often walked together in the garden, pushing the woman's wheelchair. We also had snacks together.

The following tanka poem by my father-in-law, published in a São Paulo newspaper, describes this incident.

Is it like a faint love? Pushing a wheelchair every morning and evening, an old man of 82 years

However, after the poem was published, perhaps worried about the repercussions of suddenly revealing the feelings he had kept secret in his heart, my father-in-law reverted to his teenage years. Like a child hiding from his parents after his prank was discovered, my father-in-law called his eldest son, who is a doctor, and asked him to come and pick him up as soon as possible.

It took about a week for my father-in-law to calm down, and he said shyly, "I'm going back to Ikoi-no-so." My wife, Alice, and I sent him off to Ikoi-no-so. There, the koto lady's bright smile was shining with a refreshing feeling.

I saw a side of my father-in-law that I had never seen before. I thought, "Sogro 1 is pretty good."

Notes:

1. Father-in-law

© 2013 Hidemitsu Miyamura