Editor’s Note: The following is the keynote address delivered at the 39th Annual Manzanar Pilgrimage at Manzanar National Historic Site, Independence, California on Saturday, April 26, 2008, by Dr. Arthur A. Hansen.

I would like to thank the Manzanar Committee for extending to me this invitation to be the keynote speaker at the 39th annual Manzanar Pilgrimage. I am particularly indebted for this high honor to three members of the Manzanar Committee: Cory Shiozaki, historian; Darrell Kunitomi, the chair for today’s program; and Bruce Embrey, one of the Committee’s two co-chairs.

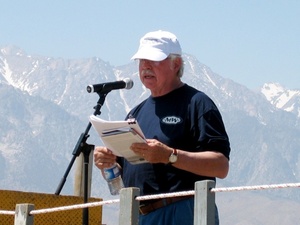

Dr. Arthur A. Hansen, giving the keynote address at the 39th Annual Manzanar Pilgrimage on Saturday, April 26, 2008. Photo: Gann Matsuda

My most profound debt, however, is to a Committee member who could not be with us today, except in spirit, and that is the late (and indisputably great) Sue Kunitomi Embrey. In addition to being Darrell’s aunt and Bruce’s mother, Sue was a founding member of the Manzanar Committee as well as the moving force behind and the public face for the Manzanar Committee during the better part of four decades.

The main purpose of my presentation—which I have entitled “The Manzanar Pilgrimage, Redressing America, and Repairing the USA”—is to explain why, in my opinion, the historical representation of the topic of the Japanese American redress movement is itself in need of being redressed in one particular respect. The respect that I have in mind is the role played by the Manzanar Committee and the Manzanar Pilgrimage, a role which has previously been grossly slighted, not only by historians, but even the Japanese American community.

The year 2008 is a very significant one for all Americans, but especially for those of Japanese ancestry, since it marks the twentieth anniversary of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. When on August 10, 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law this piece of legislation, he provided thousands of Japanese Americans with an apology and compensation for the violation of their constitutional rights that occurred during World War II when they were victimized by forced exclusion and mass incarceration.

Throughout the current calendar year there have been a dizzying number of events sponsored by Japanese American community organizations celebrating the achievement of redress twenty years ago. Typically, each of these occasions has paid tribute to select individuals or groups deemed chiefly responsible for the success of redress.

In some instances, the heroes of redress are said to be individuals and groups whose actions during World War II were so noble that, while not being directly responsible for redress, acted either to inspire it or legitimate it in the eyes of the American public and its elected representatives.

Among those in the latter camp are Japanese Americans who served the US cause during the “Good War” in three of the most celebrated and decorated units in American military history: the 442nd Regimental Combat Team; the 100th Battalion; and the Military Intelligence Service. Those who see these soldiers as the key enablers of redress argue that the men in these units served with distinction—despite the racism, discrimination, and wholesale violation of constitutional rights to which they were subjected—and it was their actions that would ultimately refute any allegations of disloyalty or treason, and thus provide the moral and patriotic capital necessary for funding redress.

On the other hand, the proponents of World War II inspirers of redress point to the actions of specific courageous resisters to their ethnic community’s massive oppression by the US government and mainstream society. Three individuals whose names are commonly mentioned in this connection are Joe Kurihara, Kiyoshi Okamoto, and James Omura. All three of these men had during World War II, in addition to their significant dissenting words and deeds, advanced concrete plans to bring about postwar redress and reparations for the wrongs done to them and their community.

Most of the attention during this year’s 20-year anniversary celebrations of Japanese American redress, however, has not focused on wartime activities by individuals or groups. Rather, attention has been riveted upon those being lauded for their pivotal contributions to redress in the period spanning the interval between 1970 and 1988. Most often mentioned are the three community-based redress groups—the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR), and the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR). Whereas JACL opted for a Presidential Commission to investigate the “internment” and NCRR focused on grass-roots support for Congressional legislation for redress and an apology from the US government, NCJAR filed a class-action suit that reached the Supreme Court.

Another group singled out for their central part in the passage of redress is the contingent of Japanese American Congressional officials: Daniel Inouye and Spark Matsunaga, US Senators from Hawaii; Norman Mineta and Robert Matsui, Congressmen from California; and Patricia Saiki, a Congresswoman from Hawaii. Together, it is said, they strategically guided the redress bill through the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Still one more group of individuals whose work on behalf of redress has been acclaimed this year consists of the coram nobis lawyers who in the 1980s revived the World War II civil rights cases of Minoru Yasui, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Fred Korematsu, and thereby helped to pave the way for redress legislation.

Just a few weeks ago, the Japanese American National Museum honored the work of key Nikkei women during the redress movement. Most prominently mentioned was Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, a WWII inmate at Manzanar, who as a self-trained archivist uncovered key documents at the National Archives that led to the vindication of resisters Korematsu, Yasui, and Hirabayashi, as well as finding other documents that provided a firm foundation for filing grievances against the US government by the Chicago-based National Council for Japanese American Redress, led by William Hohri (still another World War II Manzanarian).

Arguably, though, the individual most credited with the success of redress has been Edison Uno, a San Francisco State University professor, who in 1970 introduced a resolution calling for redress at a biennial meeting of the Japanese American Citizens League, thus making redress a formal issue. Now then, Edison Uno had an older sister named Amy Uno Ishii who, in the 1970s, was integrally involved with the Manzanar Committee and the Manzanar Pilgrimage. Both were wholeheartedly embraced by Edison Uno as being of fundamental importance to the success of the Japanese American redress movement, yet their role has been strangely downplayed during this ongoing 20th anniversary year of redress.

This neglect of the salutary part played by the Manzanar Committee and the Manzanar Pilgrimage in the redress movement has been anything but benign and, in fact, constitutes what amounts to a very serious mistake. Indeed, I would contend that, had it not been for the Manzanar Committee, the Manzanar Pilgrimage, and their moving spirit, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, the redress movement, while it no doubt would have eventually materialized, almost certainly would have been substantially delayed and assumed a quite different coloration and character than it did. Let me explain.

When the first Manzanar Pilgrimage was held in 1969, it was a very loosely organized event that involved some 150-250 pilgrims. Aside from setting a precedent for future pilgrimages to Manzanar (as well as to many other sites connected with the World War II Japanese American social catastrophe), it accomplished two related objectives. It forced those involved in the actual pilgrimage both to REMEMBER THEIR PERSONAL AND COMMUNITY PAST and to confront their painful memories of discrimination and incarceration—which amounted, in effect, to taking one giant step toward seeking justice (that is, redress).

Also, because that first pilgrimage was an event covered by the major television networks—ABC, NBC, and CBS—the remembering done by the pilgrims was reverberated so as to take in thousands of other Japanese Americans—and in so doing, put them, however hesitatingly, on the road to seeking redress and reparations. Certainly, many of the Nisei who viewed the NBC segment took notice of what one former internee, Jim Matsuoka, who had spent three years of his boyhood penned up in Manzanar, answered to a reporter’s innocent question: “How many people are buried here in the cemetery [at Manzanar]?”

For this was Matsuoka’s response: “A whole generation. A whole generation of Japanese [Americans] who are now so frightened that they will not talk. They’re quiet Americans. They’re all buried here.”

While many Nisei recoiled in anger and denial at Matsuoka’s feisty accusation, it prompted many others of this generation to REMEMBER and to become predisposed to put their memories of the past to work on behalf of righting the wrongs symbolized by Manzanar and the other camps.

By the time of the 1972 Pilgrimage the Manzanar Committee had been formed and it added a sharper focus to the occasion while broadening its concern from the process of personal and community therapy through memory to that of linking up the events associated with what Japanese American had experienced during World War II with what was currently going on in American society and elsewhere in the world. Consider these words by Sue Embrey at the 1973 Manzanar Pilgrimage:

Manzanar is a symbol. It symbolizes the ultimate negation of American democracy, and that is the racism that’s been in the United States. Even today while we are at the Pilgrimage, it is going on in Vietnam, with the strategic hamlets and Asians killing Asians, because there are Asian Americans being drafted to fight in Vietnam. You people who are spending the day here at Manzanar for this pilgrimage, should keep it in your minds that it could happen to someone else, and I hope that you will be in the very forefront of defending people so that it doesn’t happen to them.

These two roles of the Manzanar Pilgrimage, as galvanized by the Manzanar Committee—remembering the harsh past of the Japanese American community and drawing upon this memory to confront present injustices to secure a safer and saner future—have continued right up through all of the pilgrimages to this present 39th one. This is the legacy of the Manzanar Pilgrimage and the Manzanar Committee, which, in the words of this year’s Pilgrimage theme, needs to be “continued.”

We need, always, to keep in mind what a pilgrimage is. I have found one definition for a pilgrimage, by Benedictine monastic Macrina Wiederkehr, which I feel encapsulates its essence as applied to the present context. Here is what this writer and spiritual guide has to say about a pilgrimage in her 2000 book Behold Your Life: A Pilgrimage through Your Memories

A pilgrimage is a ritual journey with a hallowed purpose. Every step along the way has meaning. The pilgrim knows that life-giving challenges will emerge. A pilgrimage is not a vacation; it is a transformational journey during which significant change takes place. New insights are given. Deeper understanding is attained. New and old places in the heart are visited. Blessings are received and healing takes places. On return from the pilgrimage, life is seen with different eyes. Nothing will ever be quite the same again.

This was the great gift of the Manzanar Pilgrimage to the redress movement. It forced Japanese Americans to view their lives—past, present, and future—with different eyes, and it gave them the desire and the strength to move mountains. The Manzanar Pilgrimage endowed the Japanese Americans with a will toward righteousness and pointed them in the direction of ways to achieve it.

* This article was originally published in the Manzanar Committee blog on April 30, 2008.

© 2008 Arthur A. Hansen