Read Part 4 >>

AND IN THE NEW WORLD

There was a brief period of interest in ‘Things Japanese’ in America, prior to the Civil War (1861 –1865). Undoubtedly, James McNeill Whistler1 (1834-1903), and Mary Cassatt2 (1844-1926), both expatriates by choice were heavily affected by Japonisme. However, John La Farge (1835-1910) should be considered as an earlier proponent of Japonisme in the United States. Since about 1859, La Farge, a talented and extraordinary painter, muralist, glass artist, interior decorator and writer, began applying much of the enlightenment he had found in the Japanese prints to his own vast work.3

In 1869, La Farge was the first western artist ever to publish an essay on Japanese art, noting the fascinating attributes of the Japanese print.4 In 1863, he tried to popularize the Japanese prints which he had so enjoyed since 1854. He failed miserably. Initially, American intellectuals yawned or sneered at ukiyo-e as unworthy of consideration as a traditional Japanese style;5 but the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition debunked that. Infatuated with the prints, American nouveau-riche began competing in earnest with the European plutocrats for the best of Japanese creativity, and entrepreneurs came to view America as a fertile region where fortunes could be made if the “natives” could be encouraged to acquire Japanese objects.6 Siegfried Bing, Tadamasa Hayashi, Arthur Liberty; Louis Comfort Tiffany,(1848-1933) and their Japanese artist-suppliers all added fuel to the fire, as they realized that just then was the time in America to launch Japonisme-7 straight or in any of its derivatives.

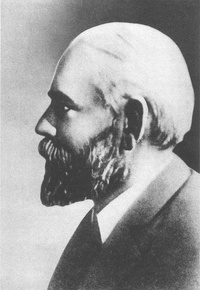

Ernest Francisco Fenollosa, (1853-1908), Edward S. Morse, (1838-1925), and William S. Bigelow (1825-1926)8, appear during that period as the most brilliant American stars of Japonisme. Fenollosa, at first an earnest detractor of ukiyo-e, was the ideal prod to push the American public into a better understanding of Japan, where he worked laboriously for twelve long years, and rose to be the world’s top expert on Japanese art. He helped found both the Tokyo Fine Arts Museum and the Tokyo Academy of Art. Emperor Meiji appointed him director of an Art Committee for the Preservation of Japanese Art, which produced the catalogue of National Treasures. For his efforts, he received both the Order of the Rising Sun, and Order of the Sacred Treasures.9

Morse, a revered figure among the cognoscenti in both America and Japan, is especially remembered for his archaeological work that unearthed the treasures of pre-historic Japanese pottery, until then almost unknown,10 and for his outstanding book on the Japanese home.11 Together with Fenollosa, Morse also fostered the concept of National Treasures, which protected many priceless antiquities from being wantonly exported to foreign countries.

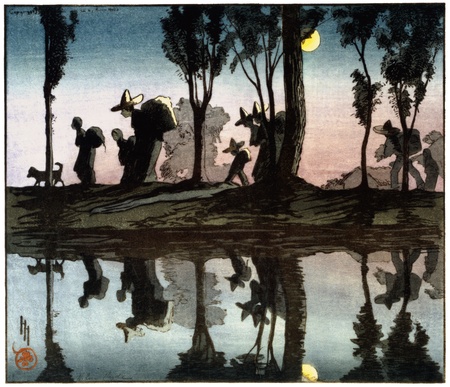

Other American artists meriting special recognition are Helen Hyde (1868-1919) and Bertha Lum (1875-1954), whose Japoniste influence is especially shown in their touching woodprints about children.

Both the 1893 Columbian Exposition, with its spectacular Ho-oden Hall12 and the 1904 St. Louis World Fair with its fascinating collection of Japanese arts, moved America to explore other facets of japonaiserie.13 Architects Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) and the Greene brothers, Charles (1868-1957) and Henry, (1870-1954) awed by the elegant simplicity of both the Ho-oden, and Morse’s Japanese Homes, decided to infuse Japonisme on American architecture.

In the early 1900’s in Los Angeles or Pasadena, you could live in a Japanese-styled aeroplane, a four-square or an avant-garde Craftsman bungalow.14 A Tiffany lamp in your living room; a piece by René Lalique in the lady’s boudoir; a front yard manicured in the Japanese style by an Issei gardener, and your most recent ikebana arrangement, all could be added as extra touches of au-courant know-how.

Curiously, as some sectors of American society were becoming more and more smitten by Japonisme, others were creating an intolerable atmosphere of injustice and discrimination against all Asians. Leaving aside previous travesties, here are some of the most notorious events illustrating the absurd situation of those days. On May, 1882, Congress overrode the veto of President Garfield against the Chinese Exclusion Act, which controlled the immigration of Chinese and other ‘Orientals’ to America, and forbade the naturalization of those already here. In June 1894, a US District Court determined that Mr. Saito, an Issei requesting naturalization, could not qualify for citizenship: he was neither a “free white person” nor “of African descent.” That decision left the Issei in America as persons without a country.15 In 1905, 67 American Unions formed the Asiatic Exclusion League to spread anti-Asian propaganda and restrict immigration; and in 1907, Japan was forced into the charade known as the Gentleman’s Agreement, under which it agreed to limit the emigration of most adult males to America. These and similar ugly repressions did not end until 1965.16

Through his superbly written and richly illustrated books: Japonisme Comes to America; Japonisme: An Annotated Bibliography and The Origins of L’Art Nouveau – The Bing Empire, all cited previously, Dr. Gabriel P. Weisberg and his collaborators lead us through those splendid days of artistic inquietude. Then comes 2010, and with it The Orient Expressed,17 which despite the noetic limitations of the subtitle– Japan’s Influence on Western Art 1854-1918, really takes us beyond those dates in a refreshingly sequential analysis of the movement, and its historical, geographic, artistic, psychological, and socio-cultural approaches.

Notes:

1. For an excellent essay on his work, see Aileen Tsui, “Whistler's La Princesse du pays de la porcelaine: Painting Re-Oriented,” Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide, Volume 9, Issue 2 | Autumn 2010 at: http://19thc-artworldwide.org/

2. Lambourne. 41-44.

3. Henry Adams, “John LaFarge’s discovery of Japanese art: a new perspective on the origins of ‘Japonisme,’” The Art Bulletin, September 1985, vol. 67, #3.

4. “Essay on Japanese Art” in Raphael Pumpelly’s Across America and Asia,(New York: Leypoldt & Holt, 1870).

5. Yamato-e, Bhuddist formal sculpture, the splendor of textiles, and the grace of the Japanese ancient pottery, for example.

6. Julia Meech and Gabriel P. Weisberg, Japonisme Comes to America, (New York: Harry N. Abrams,1990) 40.

7. Meech, 23-39.

8. http://bigelowsociety.com/rod8/wil82311.htm

9. Nash, 42-53.

10. Edward Kidder, Ancient Japan, (Oxford: Elsevier – Phaidon, 1977), 16-9.

11. Edward S. Morse, Japanese Homes and their Surroundings, (New York: Dover, 1961), (reprint of the 1886 original, Ticknor issue).

12. For an online tour of the Fair, see: http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ma96/wce/title.html

13. Japonaiserie is the term chosen by Van Gogh to name the influence of Japanese culture on western art.

14. Built, furnished, and decorated by the Greenes.

15. Brian Niiya, ed., Japanese American History: An A-to-Z Reference from 1808 to the Present, (New York: Facts on File, 1993), 32; 118-9.

16. The discrimination ended with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. However, immigration quotas were still retained. See Moritoshi Fukuda, Legal Problems of Japanese Americans, (Tokyo: Keio Tsushin,1980).

17. Jackson, Mississippi Museum of Art, in association with University of Washington Press. 2010.

© 2012 Edward Moreno