Read Part 3 >>

JAPANESQUE

Across the Channel, some distinguished British diplomatic officials became assiduous students of the Japanese language, history, life and manners. Then, after personally experiencing Japan, they began publishing their own works.

Capt. Francis Brinkley, (1841-1912) a prominent British intellectual, set foot in Japan in 1867, never to return. He established the Japan Mail-the granddad of the current Japan Times1- a publication he enriched with his passion and vast knowledge. He also authored several language text books, and his magnificent A History of the Japanese People, which Encyclopaedia Britannica published after his death.

British diplomats Sir Rutherford Alcock, Algernon Bertram Mittford, Lord Redesdale, (1837-1916), William George Aston, (1841-1911), Sir Ernest Mason Satow, (1843-1929), Professor Basil Hall Chamberlain, (1850-1935),2 Sir Edwin Arnold (1832-1904);3 and their contemporary, American journalist Lafcadio Hearn, (1850-1904)4, all helped enrich the early literature about Japan.5 From their combined efforts, Japonisme rose from art fad to the more serious Japanology, from whence ultimately emerged the discipline of Japanese Studies—Burty’s dream of a new field of study.

With the British Isles just across a narrow strait, Siegfried Bing wouldn’t just sit comfortably in France to enjoy his fortunes. He expanded his activities to popularize Japanese art in a nation already quite familiar with Orientalism.6 But the primary force that pushed the taste for Japanese art in England was Arthur Lasenby Liberty. Liberty’s business, originally India House, became Liberty & Company.

From its excellent address in classy Regent Street, it set the bar for sophisticated taste by hiring talented, creative artists, most of them already steeped in Art Nouveau styles. The result became known as the trendy Style Liberty. Liberty maintained close relations with the best designers in both the Art Nouveau, and Arts and Crafts movements. It offered the most striking decorative art in the most tempting settings. And soon, the company was attracting clients from all over Europe and America. Then, perhaps just to be different, England translated ‘Japonisme’ into ‘Japanesque’.

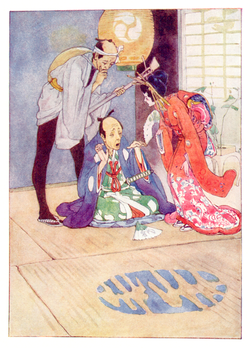

Original - Alice B. Woodward's frontispiece to The Story of the Mikado (1921), W. S. Gilbert's last literary work: a posthumously-published retelling of the plot of The Mikado for children.

Around 1885, to satirize the British government, institutions and customs, authors Sir William Schwenk Gilbert, and Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan wrote their operetta The Mikado. They disguised their characters as Japanese nobility. The piece attained a most extraordinary success, perhaps because the authors, under the shibboleth of British humor, loaded their work with innumerable racist clichés.7

Other distinguished figures of this same period are William Anderson, (1842-1900), and the short lived and highly controversial Aubrey Beardsley, (1872-1898). Dr. William Anderson was a British surgeon who, during his long years of service in Japan as Medical Officer to the British Legation, became an avid collector of ukiyo-e. In 1878, he wrote History of Japanese Pictorial Art for Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. After his return to England, he produced a second and more detailed work: The Pictorial Arts of Japan (1876). Thanks to him and other collectors, including Sir Ernest Satow, the British Museum accumulated some 20,000 Japanese prints, which it then made available to the public in 1893. By then, as Berger states, “Japanese art was more accessible in London than anywhere else in the West.”8 And thanks to all the groundwork already done by outstanding British scholars, England was also the intellectual citadel of Japonisme. In 1895, the Japanese government honored Anderson with an appointment as Knight Commander of the Order of the Rising Sun.

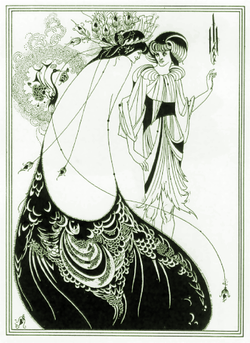

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley was an influential young artist, illustrator and writer. He played beautifully with the line over vast expanses of blank space, and all his images were always masterfully rendered. Perhaps his top fascinating pieces are The Peacock Skirt, (1893), and Child,9 this one the most sensitive and Japanesque of all his work. He also helped establish the quarterly literary magazine, Yellow Book.10 Because of his close friendship with Oscar Wilde, together with his erotic and shocking works, Beardsley became quite controversial; in the disingenuous British society, his reputation plummeted. He later converted to Catholicism, and begged his publisher, Leonard Smithers, to destroy all his bad and obscene pieces—something which Smithers conveniently forgot or ignored. Beardsley died of tuberculosis at age 25, in France, leaving behind a voluminous amount of work.

JAPONISMO

The influence of Japonisme, particularly ukiyo-e, on Spanish art has yet to be fully recognized, as noted by Dr. David Almazán.11 Probably, Catalonia is the best grounds in which to explore such impact, at least on the pictorial arts, and particularly in the works of María Fortuny, Santiago Rusiñol, Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso.12 Although Picasso often denied having incorporated Japanese motifs, styles or ideas in his paintings, the proof is in the pudding, particularly in his lewdest, erotic pieces.

Notes:

1. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/info/history.html

2. Also, according to Japanese diplomat Count Aisuke Kabayama, B.H. Chamberlain taught Japanese and Japan to the Japanese.

3. British scholar, best remembered for his work on Buddha: The Light of Asia. (London:Trubner. 1879).

4. Jonathan Cott, Wandering Ghost. The Odyssey of Lafcadio Hearn, (Tokyo: Kodansha. 1992).

5. Lord Redesdale’s most popular work is Tales of Old Japan; (1871). Aston is particularly remembered for his masterful translation of The Nihongi (1896), and A History of Japanese Literature (1898); and Hall Chamberlain for his delightful Things Japanese, (1890) as well as his two marvelous works on poetry, Classical Poetry of the Japanese (1880) and The Poetry of Japan (1911); and his scholarly translation of The Kojiki, which together with The Nihongi, are the seminal works of Japanese proto-history. Alcock was, perhaps, the most prolific and enlightened English writer about Japan during his times. See also Yokoyama, 168.

6. Yokoyama, op. cit.

7. Yokoyama, 173.

8. Berger, 107-8 and 242.

9. http://www.artpassions.net/cgi-bin/show_image.pl?../galleries/beardsleyn/child.jpg

10. The Yellow Book, a distinguished art quarterly was originally published by Elkin Matthews and John Lane. It was so named because of the color of its covers.

11. Almazán. Op.cit., N14.

12. http://www.bcn.cat/museupicasso/en/exhibitions/temporals/imatges-secretes/rooms.html

© 2012 Edward Moreno