(Presentation at a public program in support of New Birth of Freedom: Civil War to Civil Rights in California at the Orange County Agricultural and Nikkei Heritage Museum, Fullerton Arboretum, California State University, Fullerton on October 19, 2011)

As we gather here this evening next to a building called the Orange County Agricultural and Nikkei Heritage Museum, we need to reflect on the integral relationship between the history of Orange County agriculture and that of the county’s Americans of Japanese ancestry.

And while doing so, we should keep in mind that the Masuda family of Orange County was a farm family from the time that its Issei (or immigrant Japanese) progenitors, Gensuke and Tamaye, settled in Westminster in 1906 or 1907, and there, and later in nearby Talbert (today’s Fountain Valley), raised into early adulthood their large family of Nisei (or American-born U.S. citizen children) up until World War II. Thereupon the Masuda family was forced to abandon their farm and exchange their life as farmers in Orange County for imprisonment in U.S. concentration camps in California, Arkansas, and Arizona, and/or military service in the U.S. Army.

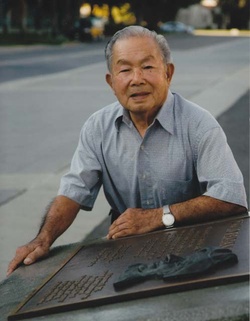

Masao Mas Masuda (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

Moreover, following the war, most of the surviving Masuda family members once again became Orange County farmers and remained so for many years of the post-World War II era. In fact, even now, the one Nisei member of the Masuda family alive today, Masao Mas Masuda, is still at the young age of 94 doing some farming at his suburban Fountain Valley home that he shares with his wife of 63 years, Lily Yuriko Masuda.

As is quite well known, agriculture has been an important part of Orange County’s history. Up until World War II, and even beyond, Orange County was rated as one of the richest agricultural counties in the entire United States. In recent decades, the onetime importance of agriculture is less reflected in the county’s changing landscape. For within the county, thousands of acres of orange groves and bean fields have been replaced, and are even today in the second decade of the twenty-first century still being replaced with homes, office buildings, and shopping malls.

There are, however, still a few remnants and reminders of the county’s bountiful agricultural past, and sometimes the neatly plowed furrows that we view as we drive around the county perform double duty in that they symbolize the county’s ethnic past as well. If agriculture has been an important part of Orange County’s history, so too have Japanese immigrants, the Issei, and their American-born Nisei children, Sansei grandchildren, Yonsei great-grandchildren, and even a few Gosei great-great grandchildren. The farmland in the county dwindles, but the memories and meanings of the farmland should not. Farming is part of the fabric of Orange County and also part of the historical and cultural weave of the county’s Japanese American community.

This fact was notably brought home at the outset of the gubernatorial administration of Arnold Schwarzenegger when he appointed a third-generation Orange County Japanese American farmer, A. G. Kawamura, as his California Secretary of Agriculture. When asked what he liked best about agriculture, Kawamura, who majored in comparative literature at the University of California, Berkeley, responded: “I like the fact that I work within nature and I like working with people in agriculture. I also like the fact that there is tremendous room for creativity in farming. There is a careful balance of art and science involved.”

During the 1870s, in the wake of the Meiji Revolution, the rapid movement in Japan toward modernization and industrialization resulted in large tax increases, high levels of poverty, and a steep reduction of agricultural land for Japanese farmers. A decade later, the enactment in the United States of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prompted American farmers to complain of a lack of labor, and this situation in turn prompted thousands of Japanese farmers to emigrate to the United States, at first to Hawaii, but later to the mainland, particularly the West Coast, and most especially California, including Orange County.

From the turn of the nineteenth into the twentieth century, when Issei workers first started to populate Orange County in significant numbers and to plow its fields and grow and harvest its crops, Japanese Americans have not only played a prominent role in the county’s agricultural production, but also contributed mightily to the steadily escalating agricultural wealth boasted by the county.

When the Japanese immigrants came to this county, the land was still in rather a wild state. As the 1890s decade gave way to a new century, roughly 31 percent of the laborers in the Orange County citrus industry were Japanese immigrants. Moreover, a large number of those who worked in this county as fruit pickers and fruit packers were employed right here in Fullerton and neighboring Placentia and other north Orange County towns. Between 1900 and the mid-1920s, Japanese laborers migrated into the county in such substantial numbers as to represent the highest percentage of people of Japanese ancestry, relative to the total population, to ever call Orange County its dwelling place.

The land in Orange County was still, even by 1900, quite unruly. But thanks in large measure to the efforts of the Japanese immigrants, the boggy bottom lands bordering the Santa Ana River were opened up to farming. Much of this land, principally that lying within the Huntington Beach/Fountain Valley area, was used to produce celery for shipping. During the first decade of the twentieth century, out of the 2000 carloads of celery that were shipped annually from southern California, 90-95 percent of it was grown in and shipped from Orange County. One third of this Orange County celery crop was raised on land share-leased by the Japanese. In 1907, this translated into 144 Issei farmers growing celery on 5,160 acres.

Strictly speaking, it was not a lease that the Japanese had, but rather a contract to do the needed handwork for celery (seeding, transplanting, weeding, hand cultivating, and gathering) in return for a share of the crop, which they preferred instead of a wage payment. As for the handwork supplied for the remaining two-thirds of the Orange County celery crop, it was practically all done by Japanese laborers.

In the thirty years between 1910 and 1940, many of the Issei, in Orange County and elsewhere, chose to return to Japan and continue their lives there. Still, a significant portion of them, in spite of being barred by law (along with all Asian immigrants) from becoming naturalized citizens and, after 1913, disallowed from owning land or leasing it for longer than three years by a series of anti-Japanese alien land laws, remained here to marry (mostly to so-called picture brides from Japan), to produce and raise typically large families of U.S. citizen Nisei children, and in time to lease and, less often, to buy property in their name and, with the assistance of their toil, to transform themselves from agricultural laborers to fairly independent family farmers.

Many of these Nikkei families became well rooted within Orange County and a substantial number of Issei, and later older Nisei, assumed respected positions within both the emerging Japanese American community of Orange County and, to a decidedly restricted sense, in the mainstream Orange County society and culture.

In California as a whole, and especially in urban areas like Los Angeles and San Francisco where large Japantowns mushroomed to service their racial-ethnic communities, the pre-World War II Japanese American state population of some 70,000 people (as of 1940) was divided almost equally between those who made their living in urban and rural occupations.

In Orange County, on the other hand, an authentic Japantown never materialized. Instead, although a handful of Japanese immigrants and an even smaller number of their citizen children ran businesses in modest urban centers like Santa Ana, Anaheim, and Orange, most of the county’s nearly 2,000 Nikkei residents were dispersed across a predominantly rural landscape, with small clusters settling around community institutions such as language schools and churches. What well more than 90 percent of these Orange County Nikkei did for a living was to farm and by so doing to assist mightily in making Orange County’s 795 square miles one of the state’s and the nation’s richest agricultural areas.

Mainly, pre-World War II Japanese American family farmers contributed through the tillage of the soil and the production of various types of food, such as truck crops, field crops, poultry, and livestock. Whereas the Caucasian farmers in the county specialized in citrus, grain, potatoes, corn, sugar beets, and fruits, the extensive dimension of the county’s farm work, Japanese American farmers added to it the complementary intensive dimension.

At least five vegetables were produced in a very large quantity by pre-World War II Japanese Americans in Orange County: celery, chili, tomatoes, Kentucky beans, and strawberries. Of these crops, chili pepper was the most unique crop grown by the county’s Nikkei. For one thing, they produced the controlling percentage of chili peppers in the entire country, turning it into first a million dollar industry, and then a billion dollar one. As for the celery, the Utah type grown here by Nikkei farmers consistently brought the top price of the market. This commodity added by 1940 about a million dollars a year to the Orange County economy. With respect to tomatoes, the production of canning and marketing variety represented very big business indeed, grossing something like three-quarters of a million dollars per annum. Altogether, the agricultural income generated by people of Japanese ancestry in Orange County in 1940 represented between 10 and 13 percent of the total Orange County income.

What the prewar Issei farmers had accomplished under adverse conditions would not be forgotten by the American-born generations of Nikkei. In an event that occurred on the evening of March 31, 1984, whose sponsor was the Nisei-led Orange County Japanese American Council of the Historical and Cultural Foundation of Orange County, the Issei generation became the center of attention. Entitled “A Tribute to Issei Pioneers in Orange County," the event was held at the South Coast Plaza Hotel in Costa Mesa, adjacent to the “California Scenario” sculpture garden fashioned by arguably the world’s greatest sculptor in the twentieth century, Isamu Noguchi, who had spent a part of World War II as a neighbor of Orange County farmers in the Poston concentration camp next to the Colorado River in southwestern Arizona. Then, too, quite near to the hotel in the cultural-commercial center of Costa Mesa was a street named after a post-World War II mega-millionaire Japanese American farmer, Katsumasa Roy Sakioka. There were 660 people present that night to honor the contribution of the county’s pioneering Issei, 38 of whom were in attendance. Certainly, age alone, in most communities, and perhaps especially so within the Japanese American one, is a trait that commands, even demands, respect. But it was clear to anyone who was fortunate enough to speak to the surviving Issei that night that they represented something more than age to praise, something connected with survival, achievement, and dignity.

As Laura Saari, an Orange County Register reporter who covered this event for her newspaper, observed in her follow-up story:

[These three dozen first-generation Japanese Americans] shared stories about moving from farm to farm in an attempt to eke out a living, about men sending for ‘picture brides’ from Japan, about sisters and brothers dying in American internment camps during World War II. Second-generation Nisei, who today are successful realtors talked about their childhood homes, shacks with newspapers for wallpaper. Produce giants remembered toiling in the fields under the hot sun. They told us their stories, many of them in their native Japanese, with a matter-of-factness that tended to heighten the personal drama.

© 2011 Arthur A. Hansen