約一年半の在外研究期間を日本で過ごし、久しぶりにブラジルに戻ってきた。1996年、筆者がブラジル渡航後に身を寄せた古巣であるサンパウロ人文科学研究所(通称「人文研」)で、この稿を起こしている。「ブラジル最古の日系教育機関」と言われるのはサンパウロ市の大正小学校だが、その校舎の跡地に現在のブラジル日本文化協会ビルが建ち、わが人文研は、そのビルの三階にある。

今回は一ヶ月あまりの調査で、サンパウロ市から、州内陸部のトゥッパン、アラサツーバ、アリアンサ、プレジデンテ・プルデンテ、アルバレス・マシャード、州境を越えて北パラナのロンドリーナを周り、サンパウロに戻ってきた。ロンドリーナからサンパウロのコンゴーニアス空港までは飛行機で1時間足らず。ロンドリーナ開発の功労者氏原彦馬(うじはら・ひこま)氏が1929年にはじめてこの地域に向かった時、鉄道は州境近くのカンバラ止まりで、「目につく物は山の鳥たちと、猿の群れ位」という大森林の中をサンパウロから三日がかりでたどり着いたそうだ(沼田, 2008, p.6)。氏原氏は、英国系の北パラナ土地会社日本人部支配人となり、多くの日本人移民をこの豊穣の地に導いた(写真15-1)。

ぬかりなく

移民最初に

学校立て(沼田信一)

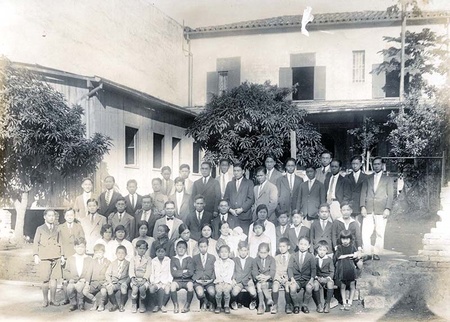

この句を詠んだ沼田氏は1932年に14歳で家族とともにブラジルに来た移民で、ロンドリーナ草分けの一人。この頃には日系植民地はサンパウロ州、パラナ州各地に広がり、日本語教育がもっとも盛んになりつつあった。1910年代には、子どもの教育などほとんど考えられなかった日本人移民も、数家族集ると「学校」を建てるのが当たり前になっていた(写真15-2)。

こうした学校教育の先駆けとなった日系植民地の一つが、今回訪れたアルバレス・マシャードである。同地は1917~18年という早い時期に開発された土地だが、「学校」ができるのも早かった。同地の第一支部小学校は、1919年12月に創立されている(サンパウロ日本人学校父兄会, 1934, p.6)。学校は閉鎖されて久しいが、現在も四方を見下ろす小高い丘の上に校舎が残っている(写真15-3)。

この丘の上で、この地域で育った三人のお年寄りのお話を聞いた。K氏(1924年生)は、「あの山の向こうに自分らはいたんだがね。山を越えて、ここまで学芸会にやってきたもんだよ」と懐かしそうに語る。往時は丘の上の校舎から、あちこちの耕地から歩いて通学してくる子どもたちが手に取るように見えたものだという。旅しながら、移民のライフヒストリーを採集していると、無数の「小さな物語」が存在するのが実感できる。

2008年のブラジル日本移民百周年前後に、日系移民に関するさまざまな出版物が発刊されたが、それらの中でも「百周年」以降の研究の出発点を示すものとして、『ブラジル日本移民-百年の軌跡-』(2010)をあげることができる。同書には、これからの「移民史研究」の流れとして、何十年史というような「大きな物語」から「小さな物語」へという方向が示されている(丸山, 2010, 75)。

筆者は、さらに無数の「小さな物語」をつむぎつつ、それらを「大きな物語」とつなげ、それら「小さな物語」から「大きな物語」を検証・再構成していく作業の必要性を感じる。その中で、日本人が地球の反対側にある南米にまでやってきて、大森林を切り開き、学校を建て、子どもたちに日本語を学ばせた意味をあらためて考えてみなければならない。そして、戦中は適性外国語として禁止され、何度もブラジル官憲の妨害を受けながらも、継承されてきた日本語・日本文化の意味が問い直されなければならない。

例えば、日本人移民の中心地であったサンパウロ市の大正小学校や聖州義塾という日系教育機関に学んだ子どもたちのことを考えてみるだけでも、多くの研究上の課題に直面する。第二次大戦後はさらに都市化が進み、日系人の多くがサンパウロ市に進出したため、同市にあった教育機関に学んだ人びとの多くが日系社会のリーダーとして活躍することとなった。彼らはいずれも二言語(バイリンガル)・二文化(バイ・カルチュラル)人として才能を発揮している(写真15-4)。

1930年代になると、子どもたちは、午前中は公立校でポルトガル語、午後は日本学校で日本語という言語的に二重生活を送っていた。大正小学校やアリアンサ小学校などいくつかの学校では、留学生出身教員や二世教員などバイリンガル教員によって授業が行われていた。結果的に意図せざる二言語(バイリンガル)・二文化(バイ・カルチュラル)教育が行われていたことになる。こうした二言語・二文化教育の萌芽は、戦後ブラジル日本語教育・二言語(バイリンガル)教育の先行実験としての性格を持ち、応用言語学や多言語教育にさまざまな素材や課題を提供する。

ソニー本社に技術研修に行ったこともあるというエンジニアのHK氏(1936年生)は戦中世代。ポルトガル語時代の大正小学校に学びながら、巡回指導で隠れて日本を習った。

「当時、先生はね。一枚一枚ばらばらにした教科書をズボンのベルトに細工をして隠して、シネイロ(ぞうり)履いて手ぶらでやってくるんだね。警察に質問されても、いかにも散歩中ですみたいな顔して。そして、今日はどこそこ、明日はどこそこと当番を決めて、けっして一ヶ所に決めずに子どもたちの家を順々に回って、日本語を教えていく。そんな時代だったね」

戦後、日本語教育が復活した時、多くの日本人元教員、二世教員たちが移民子弟教育の復活・発展に関与した。日系寄宿舎であるだけでなく、日本語教育やしつけも担った各地の奨学舎経営やブラジルで編纂された『日本語讀本』の普及、日伯文化普及会の発足やアルモニア学生寮建設など、戦前・戦中に培われた人材が、1950年代以降、多くの子弟教育分野で活躍することになった。

今、人文研のある三階からは、かつて大正小学校の校庭だったという文化協会の駐車場を見ることができる。この研究所は、日系知識人たちを啓蒙し、「日本人の移住先国であるブラジルの社会と文化を把握し、そのなかにおける日系社会の位置を確認し、そこから新しい生活と行動の理念を築き上げようという」学術的な問題を議論しあう「土曜会」が淵源である(サンパウロ人文科学研究所)。その土曜会に集った人士たち、河合武夫、半田知雄、宮尾進らは、いずれもこのシリーズで紹介した日系教育機関に学んだ移民の子たちであった。

1934年から8年間を大正小学校で学んだYAさん(1927年生)は、「大正小学校時代は、私の人生でいちばん楽しかった時期でした」と流暢な日本語で語る(写真15-5)。繰り返すが、30年代は、戦前日本語教育の黄金時代であった。その頃の校長は、はるばる信州諏訪からやってきた両角貫一氏であった。一刻者で「こわい先生」だったという両角校長も、職員室の窓から見える子どもたちの姿に目を細めていたのであろうか。

歴史はめぐる。陳腐な言い方だが… 資料が山と積まれた人文研の一室で頬づえをつきながら、筆者は、日本人街のあったコンデ・デ・サルゼーダス通りから、また市電の通っていたコンセリェイロ・フルタード通りから、ガルヴォン・ブエノ通りを、サン・ジョアキンの坂道を、三々五々歩いて通学してくる子どもたちの姿を想像してみるのである。

* * *

【付記】本シリーズを執筆するのに、多くの方々にお世話になった。資料収集のための調査では、国際日本文化研究センター、国際交流基金、早稲田大学移民・エスニック文化研究所、同志社大学人文科学研究所の研究費を利用させていただいた。また、快く在学研究に送り出してくれたブラジリア大学外国語・翻訳学部の同僚諸氏、サンパウロでの足場として利用させていただいたサンパウロ人文科学研究所、ブラジル日本移民史料館の皆さん、ロンドリーナの生き字引沼田信一氏ほか数え切れない多くの方々にご協力いただいた。いちいちお名前をあげることはできないが、この場を借りて感謝の気持ちを伝えたい。

* * *

参考文献

沼田信一(2008)『信ちゃん昔話・北パラナ国際植民地開拓五大物語(一)』

丸山浩明編著(2010)『ブラジル日本移民-百年の軌跡-』明石書店

サンパウロ日本人学校父兄会(1934)『サンパウロ日本人學校父兄會々報』第2号

サンパウロ人文科学研究所「土曜会からサンパウロ人文科学研究所、そして現在へ」

http://www.cenb.org.br/cenb/index.php/articles/display/27 (2011年8月1日アクセス)

© 2011 Sachio Negawa