戦前期から戦後期にかけて、海に囲まれた日本から外国への移民は、ほとんどすべてが海上輸送に拠っていた。移民船は海外渡航の主役であり、移民の誰もが船内生活を経験したものだった。

「洋上小学校」(船内小学校)は、移民船内で開校された小学校である。ブラジル移民は、家族移住が主であったので、主婦である女性や子どもたちが多く含まれ、航海中の賑わいや華やぎをあたえていた。洋上小学校は、小学校学齢期の子どもたちを対象とするものであり、航海日数のとりわけ長かったブラジル移民にもっとも多くの例が見られた。日本からブラジル、ブラジルから日本という、両国を往還した子どもたちの教育機会や日本的教育の連続性を考える場合、洋上小学校の存在は軽く扱うことはできない。

山田廸生氏の『船にみる日本人移民史-笠戸丸からクルーズ客船へ-』(1998)は、移民船から移民史をとらえ直した好著だが、移民船らぷらた丸の第23次航(1936)で開校された「らぷらた尋常小学校」を例に、洋上小学校について次のように紹介している。

「らぷらた丸」第二三次航では、高等科併設の「らぷらた尋常小学校」の開校式が、神戸を出て四日目に特三食堂1で行なわれている。開校式は開式の辞に始まり、『君が代』斉唱、宮城・伊勢神宮遥拝、校長訓示、教師紹介、来賓祝辞、閉式の辞と続く立派なもの。来賓には田崎・上塚の両名士、それに舟の事務長が招かれた。現職の大学学長と国会議員が祝辞を述べているのだから、洋上ではあるがなかなか豪勢な開校式だった。校長にはこの航海では輸送監督が当たっている。

学童数は高等科を含めて五○人。二学年が一組の複式学級で、授業は午前、教室は特三食堂である。学級数は四組だから、教師が四人必要なわけだが、よくしたもので、大勢の移民のなかには教員経験者がおり、子どもたちの指導を引き受けてくれた (山田, 1998, pp.182-184)。

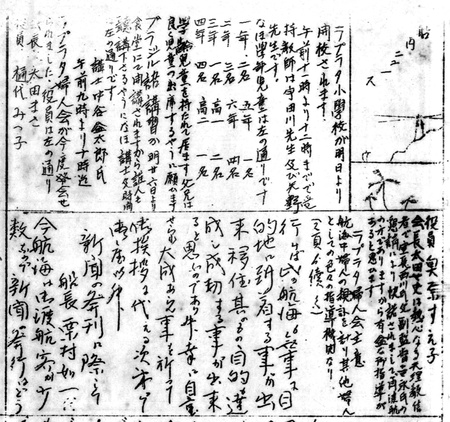

移民船内の生活を伝える資料として、まず移民船客自身が執筆・発行していた船内新聞をあげることができる。先の山田(1998)も、船内新聞の記事を多く引用している。商船三井社史編纂室や日本郵船博物館から、いくつかの船内新聞のコピーを提供していただいた。これらの中には、移民船内で小学校の開かれた様子が生き生きと伝えられている(写真14-1)。例えば、「若狭丸小学校」、「さんとす村小学校」というように船の名前を冠し、船長や輸送監督が校長、船客の中から教師経験者を見つけて教師とし、ブラジル到着前には修了証書まで授与されていた。航海中たびたび行われた運動会でも、「一、旗取り競争 小学校児童」「九、椅子取り競争 小学女生徒」「十八、スプーンリレー 小学校児童」というように、小学生の活躍の様子が見られる(大阪商船, 1939)。

らぷらた丸の22次航(1936年11月~1937年3月)の船内新聞「らぷらたタイムス」によると、校長は船長や輸送監督ではなく、他の乗船者から選ばれたようである。また、航海途中で、教員も交代している。やはり乗船者から選ばれた教育係は、徽章として白赤のリボンをつけることになっていた(大阪商船, 1935-1936)。らぷらた丸の25次航(1937年2月~1937年6月)では、小学校校長は輸送監督の森岡吉郎氏になっている(大阪商船, 1937)。洋上のことであり、何ごとも臨機応変の処置がとられていたようである。

ブラジル移民と他の地域への移民との違いは、その行程の長さである。神戸からサントスまでは、第1回移民の笠戸丸で52日、後述する辻小太郎の乗った備後丸で63日、1929年に就航した大阪商船の「優秀ディーゼル船」ぶえのすあいれす丸、りおでじやねろ丸で46日、1930年代末の「移民船の決定版」と呼ばれたあるぜんちな丸などの高速船でも34日の長さである。この長い航海を無事に、無聊をなぐさめ楽しみつつ、またブラジル生活の準備期間として有為に送るために、船会社も移民会社も、移民たち自身も、さまざまな工夫をしたのである。赤道祭や運動会、演芸会、仮装大会、ポルトガル語講習会、洋裁教室、青年団や婦人会の活動、そして小学校の開校など、陸地でのコミュニティ活動に準ずるものであった。笠戸丸では、すでに赤道祭が開かれ、沖縄の三線や空手踊り、新内節、相馬節、詩吟、尺八演奏、仮装行列などが演じられたことが知られる(細川, 1995, p.15)。

戦前の移民に当てられた三等船室は狭く、生活空間としても劣悪だが、時間は腐るほどあった。ただ、時間を持て余した元気な子どもたちが一日中船内を走り回るのも危険で問題がある。先生も都合よく見つかったものだと思うが、幼稚園も開かれていることから、洋上小学校は教育機関であるとともに、託児所的な意味合いが強かったという2。長い航海の間、子どもたちが楽しく安全に日を送り、親たちを安心させるために必要不可欠なものとして生れたサービスではなかったか。

1928年7月25日、移民輸送事務官として神戸出港の備後丸(日本郵船、写真14-2)に乗り込んだ辻小太郎(1903~1970)の手記『ブラジルの同胞を訪ねて』(1930)によって、乗船後の「備後村」立ち上げによる船内生活のはじまり、小学校開校までを見てみよう。

自分は一同を合して一団とし、自治体を組織して備後村と称し、船席によつて八区に別け、各区を七家族とし、区長兼村会議員一名を選出するため満二十歳以上の男子には選挙権並に被選挙権を与え、自分自身村長に就任し、助手を助役とし合計十名にて村会を組織し、一同に関することは此の会議の多数決によることとした。

次で十五歳以上三十歳以下の男子にて青年団を組織し、総務部、運動部、弁論部、語学部、風紀衛生部、編集部、催物部を置き、各分担を定めて責任を負はしめ、総務部は各部長を以て組織した。

(中略)小学校は教育に経験ある人三名を教員に任じ、他に学務委員一名を置いて之が世話に当ることゝした。

(中略)一等甲板で村会が開かれて、上陸問題の議せられてゐる時、反対側の甲板では青年団総務会が開かれて碇泊中の警備の問題、服装の問題が議せられ、前甲板には幼稚園が始つて可愛い子供が鳩ポッポをやり居り、後甲板では小学校が始つて、三組の生徒が一生懸命勉強して居り、衛生組合ではトラホーム患者の治療について全力を集注してゐるといふ有様であつた3 (辻, 1930, p.4-5)。

ちなみにこの回の備後丸では、小学生の学芸会の他、3回の運動会、討論会、撃剣大会、演芸大会、活動写真会、カルタ会が催され、ブラジル国歌の練習も行われた(同書, p.18)。

こうした洋上小学校が、いつごろからはじめられたのかは、今のところ明らかではない。1917年のしあとる丸の「葡語講習会」の写真が残っている。屋外の甲板上で、背広姿の講師を前に着物姿で腰掛けてテキストを開いているのは大人の男たちである(国立国会図書館)。小学校の例としては、1924年のしかご丸ですでに実施されていたことが同船の船内新聞「トナンタイムス」から確認できる。しかご丸には、さんとす丸級のような特三食堂がなかったはずなので、小学校はやはり甲板で開かれていたのであろう。

洋上小学校の開設は、1920年代にはじまるブラジル向け移民の国策化の動きと何らかの関係があると想像される4。1921年、内務省社会局から海外興業株式会社および移民への補助として10万円が予算化され、「教養費」として「船内学校等航海中の教材、娯楽費」7821円が計上されている(飯窪, 2003, p.43)。「船内学校」が洋上小学校を意味するのか明らかではないが、1928年(2万5400円)まで「教養費」は年々増加しており、1924年には、ブラジルまでの船賃を日本政府が全額補助することになった。こうした動きの中で、洋上小学校もはじまったのではないか。

この洋上小学校の誕生によって、移民子弟の教育は、少なくとも大正末期に入ってからは、渡航によって断絶が避けられることとなった。日本的教育の実践は、出身母村の小学校から洋上小学校を経て、ブラジルの日系教育機関まで連続していたことがうかがえる。移民船は「人間を積む貨物船」と呼ばれ、ずいぶん過酷なイメージがつきまとうが、ある時期から洋上小学校という人間らしい営みも行われていた事実は、教育史の点からも見落とすことができないであろう。

注釈

1. 1925年に就航したさんとす丸級以降の大阪商船の各船に特別三等食堂が設けられ、画期的な公共空間となった。食事時以外は、出港後のオリエンテーション、船内自治組織の会議や行事、小学校やポルトガル語講座の教室などに活用された(山田, 1998, p.111)。この特三食堂という公共空間の出現によって、ある程度天候に左右されず、船内での教育・文化活動ができるようになったと考えられる。

2. 黒田公男氏のご教示による。

3. 引用に当っては、旧漢字を新漢字に適宜あらためた。

4. 山田廸生氏のご教示による。

参考文献

飯窪秀樹(2003)「1920年代における内務省社会局の海外移民奨励策」『歴史と経済』第181号政治経済学・経済史学会

国立国会図書館「葡語講習会(シアトル丸船内)大正6年6月30日」「ブラジル移民の100年」

http://www.ndl.go.jp/brasil/data/R/008/008-001r.html(2010/11/29アクセス)

辻小太郎(1930)『ブラジルの同胞を訪ねて』日伯協会〔石川友紀監修(1999)『日系移民資料集南米編14巻』日本図書センターに再録〕

「日本郵船所有の船舶」http://homepage3.nifty.com/jpnships/company/nyk_meijikoki1.htm(2010/11/29アクセス)

細川周平(1995)『サンバの国に演歌は流れる-音楽にみる日系ブラジル移民史-』中央公論社

山田廸生(1998)『船にみる日本人移民史-笠戸丸からクルーズ客船へ-』中央公論社

船内新聞

大阪商船(1935)「船内新聞:らぷらた丸21次航」

大阪商船(1935-1936)「船内新聞:らぷらた丸22次航」

大阪商船(1937)「船内新聞:らぷらた丸25次航」

大阪商船(1939)「船内新聞:りおでじやねろ丸第22次航」*

*以上は、商船三井社史編纂室よりご提供いただいた。

「トナンタイムス」(1924)(しかご丸船内新聞)

© 2010 Sachio Negawa