(INITIAL NOTE: Assuming that the information contained in this text is not restricted to a particular group, we ask non-Chilean readers to replace the word “Chilean” with his or her own nationality, while accepting the few historical notes found therein.)

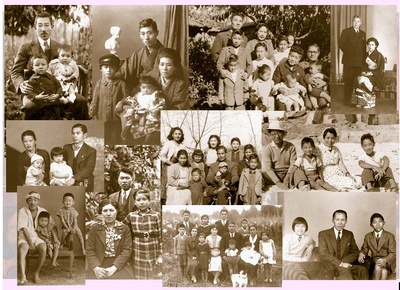

‘Nikkei’ concept apparently became applicable to Chile only after the first decades of the 20th century. It is a given that Japanese presence in our country dates back as early as 1875. The population census of that year registered the presence of two Japanese on Chilean territory, while by 1885 their number reaches 51; in 1895, however, that figure abruptly drops to 20. Relying only on that data, it’s clear that those were Japanese dekasegi, adventurers who lived in the country only for a few years before returning to their families in Japan. Thus, their presence is ephemeral, being reduced to mere figures. The same doesn’t happen in the 20th century, when the dekasegi become part of an unplanned immigration. Although the nationalism ingrained in those Issei make them expect to return home each year, fate has assigned them new missions in these lands at the end of the world.

In time, each one of them ends up profoundly influenced by everything new that surrounds them: customs, language, laws, religion, beliefs, tastes. The enormous ocean-wide distance separating them from barely known fellow nationals scattered throughout a large area means that their traditional collectivism can no longer provide them shelter. But they have the understanding of life’s worth, of time that cannot be wasted, and of an inheritance that must be left behind. With eyes set on the strange, though generous land they begin to delineate their own domains, making use of the good things they find in abundance. They select sources of labor, knead wheat-bread dough, learn the word yo [“I”] and rewrite their last names, usually adding Chilean blood to it.

Whether aware or unaware of it, they have left behind the Fatherland—a Fatherland that has paid them in the same coin as it also needed to learn to walk along new paths with other of its children. In order to give birth to the “Chilean Nikkei,” our pioneers had to first of all be transformed into the first “Nikkei.”

* * * * * * * * * *

- INDEFINITE STAY

- MIXED MARRIAGE

- CHILEAN CHILDREN

- CULTURAL ACCOMMODATION

- COMMUNITY INTEGRATION

- NIKKEI

* * * * * * * * * *

Their battered but still-remembered collectivism continues to support them within the realm of the family, so that this alien society will not take away their last bastion. Also, their genetic background and stubbornly persistent culture ensure that the basis of their ancestral morality is passed on to each new generation. As a result, each Nikkei becomes the repository of an inheritance with identity-building power. But after almost one century, the now grown “Nikkei family” continues to strive to preserve its original structure. They keep identifying themselves solely on the basis of their blood ties, thus leaving aside a large segment of its extensive scope. The 2001 New York COPANI clearly defines who the Nikkei are. When we apply this broad criterion, we discover that our few members are multiplied almost as if by miracle for they have remained marginalized as a result of either ignorance or childish sectarianism.

* * * * * * * * * *

DEFINITION OF THE NIKKEI CONCEPT AT THE 2001 NEW YORK COPANI

1. NIKKEI BY BLOOD

2. NIKKEI AS A RESULT OF SOCIAL OR LEGAL TIES

3. NIKKEI AS A RESULT OF PERSONAL TIES TO JAPANESE CULTURE

* * * * * * * * * *

The difficult work performed by those early pioneers and their descendants allowed them to gain acceptance and respect from local communities. In addition, beginning in the early ‘80s Japanese growth has indirectly led to an increase of this recognition. Among all walks of life in the local community there’s a surge of interest in and appreciation of Japanese goods and cultural manifestations. In addition to giving preference to mass products of Japanese provenance, some become avid manga readers, they imitate and discuss anime characters, while sushi becomes a lasting trend, more people develop ties with Japanese history and its cultural manifestations, academic studies are created to teach the Japanese language, and for those who have a Japanese family name doors are opened an extra inch.

This increased proximity to Japan, plus the frequent contact with is visitors and today’s greater ease to visit that country—so as to experience both its wonders and its many realities that are alien to us—should help to fully clarify the real Nikkei identity, thus leaving behind assumptions about a Japanese lineage that is no longer based on fact. It’s now time to allow the blossoming of pride to be Chilean with Japanese genetic and/or cultural background which makes us special. Our forefathers had already pronounced that when they remarked: “If you’re going to live in Chile, be Chilean.” Following this key achievement, all that’s missing is the last step.

* * * * * * * * * *

THE CHILEAN NIKKEI’S REALITY

1. STRONGLY INFLUENCED BY THE NATIONAL AND WESTERN CULTURES

2. LACKING FORMAL JAPANESE FRAMEWORKS ON WHICH TO SUPPORT HIMSELF

3. STRONGLY CONCERNED WITH HIS FAMILY (EDUCATION, RESPECT TO LAWS AND HONOR)

4. HAVING LITTLE CONTACT WITH OTHER NIKKEI 'BY BLOOD'

5. LACKING AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE SCOPE OF THE NIKKEI CONCEPT

* * * * * * * * * *

Today, it’s possible that the world has placed us at a decisive crossroads. Globalization requires a “planetary” man that has been made uniform in terms of knowledge, capacities, inclinations, laws, and morality; alien to borders, languages, or gods. Of course, in such a scenario minorities become the most vulnerable groups. Could we disappear as a Nikkei minority? It’s difficult to come up with an answer because the Nikkei aren’t an ethnic group, but nationals of various countries, with different characteristics, but who carry within themselves something extra that both distinguishes them from others and keep them united. In our case, we are Chileans with a Japanese “something,” just like other Nikkei who are North Americans or Cubans, but who also possess that same “something.” For us to lose those special attributes and that typical Chilean idiosyncrasy would be a disaster in every way.

In order to fight this possibility of annihilation, maybe it would be enough to put into action Mahatma Gandhi’s “passive opposition.” Beginning with the awareness of our present positions, virtues, and limitations, and then fine tuning and honing these capacities which are our own so they can continue to develop until we become capable of performing to perfection the assigned role corresponding to each Nikkei within his specific realities.

* * * * * * * * * *

WILL THE CHILEAN NIKKEI DISAPPEAR?

- IF THEY DON’T BECOME INTEGRATED WITH THE ‘CULTURAL NIKKEI’

- IF THEY DON’T COMPREHEND THE DISINTEGRATING POWER OF GLOBALIZATION

- IF THEY DON’T ELIMINATE BORDERS WITHIN A NEW COLLECTIVISTIC FRAMEWORK

- IF YOUNG PEOPLE DON’T INTERNALIZE THE NIKKEI CONCEPT

- IF EACH ONE OF US DOESN’T BEHAVE AS A LEADER BY WAY OF HIS ACTS WITHIN THE COMMUNITY

* * * * * * * * * *

* The above article is the result of the discussions that took place at the session “Multiracial / Multi-ethnicities in Nikkei Communities” in the workshop organized by Discover Nikkei at the XV COPANI, held in September 18 in Montevideo, Uruguay.

© 2010 Ariel Takeda