Em 18 de junho de 2008, a imigração japonesa completou seu primeiro centenário no Brasil.

O ensino de língua japonesa começou no contexto da imigração (Doi: 2006). No início, muitos imigrantes foram enviados para o interior do estado de São Paulo, na condição de colonos, para substituir a mão de obra escrava nas fazendas de café. Depois de cumprir contratos e alcançar uma condição econômica mais estável, por volta da década de 1920, começam a surgir núcleos de japoneses, constituídos por proprietários de pequenas terras e arrendatários. Assim, muitas colônias de japoneses se formaram nas zonas rurais ao longo das linhas ferroviárias (Noroeste, Paulista e Sorocabana) do estado de São Paulo, construídas no auge da lavoura cafeeira.

Da região oeste do interior de São Paulo, muitos imigrantes rumaram também para o norte do Paraná em busca de terras férteis, fixando-se por lá. São as cidades de Londrina, Maringá e adjacências, onde também há uma grande concentração de japoneses e seus descendentes. Outras colônias foram formadas também em estados do Pará, Amazonas, Mato Grosso do Sul, por exemplo. E nessas cidades onde há japoneses, normalmente se encontra uma escola comunitária (EC).

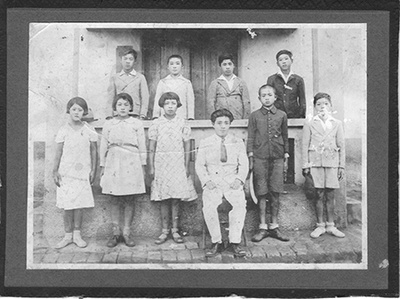

2ª. Formatura da Escola Japonesa de Fukuhaku (6º.ano do primário) Suzano, São Paulo, dezembro de 1938. Arquivo pessoal: Sr. Fumio Oura

24º. Seminário Nacional de Professores de Língua Japonesa do Brasil, São Paulo, 1974. Arquivo pessoal: Professora Sumie Fuchida

No livro História da Educação Japonesa da Alta Paulista (1941), um dos raros registros sobre a educação japonesa do período pré-guerra na visão de professores, há relatos de formação de ECs nos núcleos de imigrantes, nas redondezas da cidade de Marilia e adjacências (linha ferroviária Paulista), entre as décadas de 1920 a 1930. Nessas descrições, é possível compreender como as ECs brotavam – quase que espontaneamente - em cada um dos núcleos, como um sistema de educação informal nas mãos de voluntários e professores contratados.

Nas ECs, o japonês era ensinado sob a perspectiva da Língua Materna (LM), mantendo-se como língua de comunicação, uma vez que a maioria dos imigrantes pretendia voltar ao Japão. Visto sob uma perspectiva ampla, as ECs não só ensinavam o japonês, mas também preenchiam uma carência do sistema educacional brasileiro, pois raramente havia escolas nas localidades em que os imigrantes haviam se instalado. Além disso, as primeiras escolas brasileiras, chamadas de Escolas Rurais, atendiam em classes multisseriadas (os primeiros três anos do primário), de modo que quem quisesse prosseguir com os estudos tinha de se deslocar até a zona urbana. Muitos descendentes acabavam indo à EC por esta oferecer maior extensão de estudos (seis anos), com livros didáticos importados.

Até haver restrições ao ensino de japonês, em 1938, as ECs funcionaram de vento em popa, seguindo um protocolo nipônico, com todos os rituais de cerimônia de início de aula, formaturas ao som de hino nacional japonês, reverência à imagem do imperador e declamação dos éditos imperiais sobre educação. Havia também aulas de educação moral e cívica e matemática, todas ministradas em japonês.

Entre 1941 a 1945, a língua japonesa foi banida da vida social e pública dos imigrantes e descendentes. Por conta da tomada de posição brasileira ao lado dos Aliados, os imigrantes tornaram-se inimigos da nação brasileira. O ensino de japonês foi proibido para menores de 14 anos, jornais e revistas em japonês deixaram de circular; passou-se a exigir salvo conduto para o trânsito fora da área residencial. Isto para não falar de medidas francamente punitivas, como a prisão de professores e líderes comunitários, incineração de livros e confisco de bens.

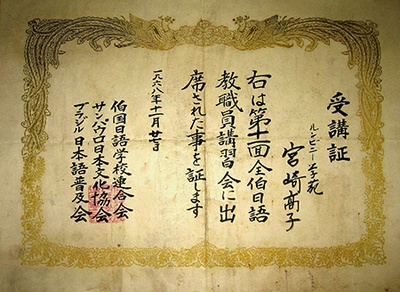

Certificado de participação no 11º. Seminário Nacional de Professores de Língua Japonesa (Zenpaku Nichigo Kyôshokuin Kôshûkai). 27.11.1968 Arquivo pessoal: Professora Takako Miyazaki.

No pós-guerra, a língua japonesa passa a ser ensinada na perspectiva de língua de herança (LH), uma vez que os descendentes passaram a dar continuidade aos estudos da escola brasileira, indo para níveis cada vez mais avançados, favorecendo o desenvolvimento do bilinguismo entre os descendentes nikkeis.

Na década de 1950, já superados os malefícios da guerra, as ECs retomaram lentamente suas atividades. Diferentemente do pré-guerra, época em que os professores recebiam orientação direta dos representantes do governo japonês, no pós-guerra, houve iniciativas em prol da oficialização das ECs, e também elaboração de livros didáticos no Brasil. Surgem, então, grupos institucionalizados, como a Federação das Escolas de Ensino Japonês no Brasil (Nichigakuren - 1954-1988), a Sociedade Brasileira de Cultura Japonesa (Burajiru Nihon Bunka Kyôkai - 1955) e a atual Aliança Cultural Brasil-Japão (Nichibunren - 1956). Mais tarde, em 1985, as três entidades se juntarão para formar o atual Centro Brasileiro de Língua japonesa, com sede em São Paulo.

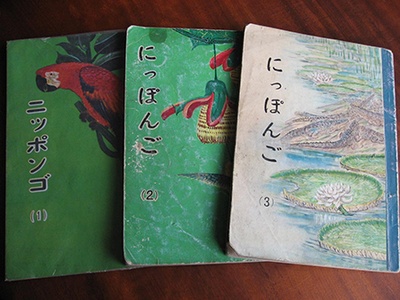

Nippongo No. 1, 2 e 3: os primeiros livros didáticos elaborados no Brasil, 1960. Arquivo pessoal: Professora Masayo Ueno

Até meados de 1980, o japonês foi ensinado como Língua de Herança (LH), uma perspectiva pedagógica que tem como alvo descendentes com domínio da modalidade oral do japonês, em âmbito familiar e ou intracomunitário. Neste caso, a função da EC era alfabetizar (caracteres fonográficos e logogramáticos) e promover o letramento. Atividades escolares realizadas neste período atestam essa tendência, reproduzindo em certa medida a vida escolar do Japão.

No pós-guerra, portanto, entre as décadas de 1950 a 1980, a função das ECs foi de complementação, agregando atividades pouco exploradas nas escolas brasileiras (públicas), como o desenvolvimento de disciplinas voltadas para as artes e música, comumente conhecidas como jôsôkyôiku (aulas de valorização na formação humanística). Além disso, outra forte atividade que mantinha a união dos descendentes era a prática esportiva, bastante difundida não só na comunidade como também havia campeonatos inter-comunitários, favorecendo um intenso contato social e cultural entre os japoneses e seus descendentes, como espaço de preservação da língua, cultura e de valores japoneses. Esse sistema, do ponto de vista do bilingüismo, possibilitou rica vivência aos descendentes em ambientes funcionalmente distintos, com objetivos diferentes, hoje largamente valorizados em ensino bilíngüe.

Curso de conversação em japonês – Aliança Cultural Brasil-Japão, Unidade São Joaquim, Método Ezoe. Professora Eliko Yoshioka, São Paulo, janeiro de 2007.

Embora questões sobre o ensino de língua estrangeira tenham sido objeto de debate desde a década de 1950 em seminários, nos editoriais de jornais japoneses editados no Brasil, é a partir de 1980 que assuntos relativos à metodologia passam a ser mais destacados em relação à concepção de ensino. A partir de 2000, a entrada maciça de alunos (descendentes e não-descendentes) sem nenhum conhecimento da língua levou os professores a uma reflexão mais aprofundada. Nesse sentido, a mudança do perfil do alunado traz novas mudanças no cenário de ensino-aprendizagem de japonês do Brasil, eliminando a fronteira étnica para o estudo da língua e da cultura, até então considerada prerrogativa dos descendentes.

Aula de música para os preparativos do Festival das Estrelas (Tanabata Matsuri)Escola de Língua Japonesa de Quatro Bocas, Tomé-Açu, Pará, 01.07.2007

11º. Concurso de Oratória em Língua Japonesa – Fase Regional (Região Noroeste de São Paulo), 14.09.1997. Arquivo pessoal: Professora Kumiko Kanematsu

Premiação do vencedor do 1º. Concurso de Oratória em Japonês (Organização: Kenren, Asebex), novembro de 2008. Felipe Augusto Motta (aluno de graduação, História, FFLCH-USP), no centro.

No âmbito das escolas públicas, a USP foi a primeira instituição de ensino superior no país a abrir curso de graduação em japonês, em 1964, e também a única – até agora – a oferecer curso de pós-graduação (em nível de mestrado) em 1996. Novos cursos de graduação foram depois criados em todo o Brasil: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (1979), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (1986), Universidade Estadual Paulista (1992), Fundação Universidade de Brasília 1997), Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro (2003) e Universidade Federal do Paraná (2009).

Desde 1987, num programa de línguas estrangeiras implantado em redes públicas de ensino, algumas escolas de ensino fundamental e médio também começaram a oferecer o japonês como disciplina extracurricular optativa. No estado de São Paulo há treze unidades de Centros de Línguas (CEL), e, no Paraná, onze Centros de Línguas Estrangeiras Modernas (CELEM), conforme dados da Fundação Japão (2006).

O Brasil, portanto, caminha para a diversidade, uma vez que, mesmo em ECs, em média, 20% dos alunos que estudam japonês são de alunos sem ascendência nipônica, enquanto que essa taxa pode ainda aumentar para 80% quando se trata de ensino público ou em ECs onde não há concentração de japoneses, tendo alcançado o japonês um estatuto de língua estrangeira.

Para se ter uma idéia da situação atual, o Brasil ocupa 13º. lugar na classificação mundial de número de estudantes de japonês; no quadro nacional, há 21.631 estudantes, 544 instituições de ensino e 1.213 professores de japonês (Fundação Japão, 2006).

Fontes Bibliográficas

DEMARTINI, Zeila de Brito Fabri. Relatos orais de famílias de imigrantes japoneses: elementos para a história da educação brasileira. In: Educação e Sociedade, ano XXI, no. 72, agosto 2000, pp. 43-72.

DOI, E.T. O ensino de japonês como língua de imigração. In: Estudos Lingüísticos XXXV, 2006, pp. 66-75.

FUNDAÇÃO JAPÃO. Diretório de instituições educacionais de língua japonesa do exterior (2006). http://www.jpf.go.jp/ Acessado em 10 de novembro de 2007.

HANDA, T. O imigrante japonês – A história de sua vida no Brasil. São Paulo: T. A Queiroz, 1987.

MORIWAKI, R. Nihongo kyôiku no hensen (A transição da filosofia norteadora do ensino de língua japonesa). Centro de Estudos Nipo-Brasileiros. No. 2, 1998, p. 71-85.

MORIWAKI, R. Nihongo kyôiku no hensen II (A transição da filosofia norteadora do ensino de língua japonesa – 2ª parte). Centro de Estudos Nipo-Brasileiros. No. 4, 1999, pp. 43-75.

SAITO, Hiroshi. O japonês no Brasil – estudo de mibolidade e fixação. Editora Sociologia e Política, 1981.

SHIBATA, H. As escolas japonesas paulistanas (1915 – 1945): A afirmação de uma identidade étnica. Dissertação de mestrado, FEUSP, 1997.

TERAKADO, Y. et. alii. Pa Enchôsen Kyôikushi (História da Educação da Alta Paulista). Nippakusha, 1941.

© 2009 Leiko Matsubara Morales