During and immediately following World War II, Americans of Japanese ancestry flooded Chicago for work and school as they were either released from incarceration at one of ten U.S. War Relocation Authority concentration camps, or discharged from military service. Prior to WWII, Chicago’s ethnic Japanese population numbered roughly four hundred; by 1945 there were twenty-thousand.

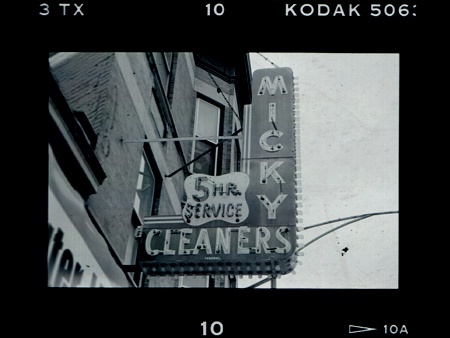

3469 N. Clark (Map Item #33)

Noboru Asato / Mamoru & Michie Yokomori

Moved from 1122 N. Clark

Current status: Extant as of 2014, under new management, at 3242 N. Clark (former site of Miyako & Shiroi Hana restaurants)

Photo courtesy of Jill Yamagiwa

Instructed by the government to not congregate back into the “Japantowns” they’d left behind, programs were instituted to assist relocatees in assimilating to the greater population. With such mass migration, however, the community naturally began building its own support networks in order to acclimate into this new environment. Largely from the West Coast with a smaller contingent from Hawaii, Chicago provided a culture shock for many resettlers.

Japanese Americans began assisting each other in finding jobs and housing; they established social, cultural, and religious institutions as well as small businesses to serve the burgeoning population; and by the mid-1940s, two distinct Japanese American neighborhoods had formed in Chicago: in the South Side Oakland community near 43rd and Cottage Grove, and on the Near North Side at Clark and Division Streets.

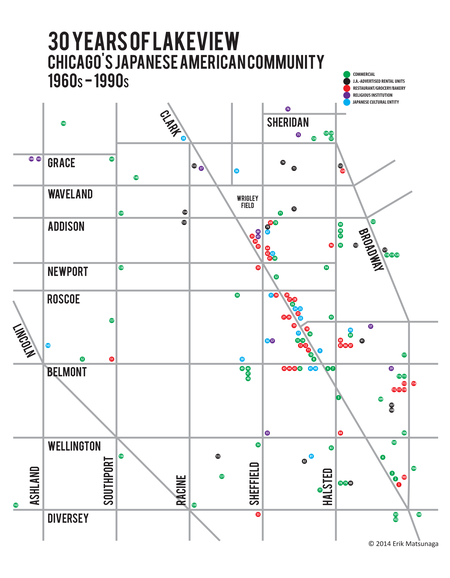

Regarding the North Side community, by the 1960s urban renewal projects began displacing residents and businesses as old buildings and tenements were razed in favor of modern high rises for middle to upper income tenants. Additionally, the Nisei craved more spacious accommodations for their growing families. Consequently, a migration of the North Side Nikkei community ensued three miles further up Clark Street into the Lakeview neighborhood, in the vicinity of Wrigley Field, bringing with it many of its businesses and institutions.

3413 N. Clark (Map Item #32)

Takeo & Martha Deguchi

Current status: Closed

Photo courtesy of the author

Ask any Japanese American in Chicago today and they’ll likely tell you the city never had a Nihonmachi, or Japantown. The government didn’t want the community congregating as such. Despite lack of formal designation, however, historically there were three distinct neighborhoods of Japanese settlement. The last, and perhaps largest, of these was in the North Side neighborhood of Lakeview, and its influence lasted the better part of forty years.

3439 N. Sheffield (Map Item #64)

Hiroto “Kaunch” & Kazuo “Zoke” Hirabayashi

Moved from 1238 N. Clark

Current status: Extant as of 2014, under new management

Photo courtesy of the author

A diverse neighborhood populated by many ethnic groups, Japanese Americans were highly visible in terms of their commercial, cultural, and residential presence, particularly along Clark Street from Belmont to Addison. Perhaps it couldn’t be considered a “Nihonmachi” in the strictest sense, but it was a “Nikkeimachi,” a diasporic community built largely by the relocated American-born descendants of Japanese immigrants.

Although the Nikkei residential presence began dispersing much earlier as the Sansei generation came of age and moved their families either outward toward city limits or into the suburbs, many businesses remained in the neighborhood into the latter half of the 1990s and beyond. Gentrification and changing neighborhood dynamics, coupled with lack of residential and commercial succession, has significantly diminished the area of Nikkei presence.

30 Years of Lakeview: Chicago’s Japanese American Community from the 1960s-1990s, offers a glimpse into a recently bygone era. Although as of 2014 a handful of historic Nikkei entities still remain as scattered afterimages of its heyday, no formal designation has ever encouraged the sustenance of this community as a geographic destination for Japanese American culture as one might find on the West Coast, or even in various other ethnic Chicago neighborhoods such as Ukrainian Village or Andersonville’s Swedish Town, where ethnic and economic demographics have changed considerably across generations while maintaining the culturally unique footprints that have forged Chicago’s renown as a “city of neighborhoods.”

According to current and former Lakeview residents:

3435 N. Sheffield (Map Item #62)

Thomas Yamauchi / Chester Joichi

Current status: Closed.

Photo courtesy of the author.

“My father, Tom Yamauchi, founded the Hamburger King sometime around 1954 or 1955. It was originally just a six‐seat counter restaurant located on the very tip of the triangle formed by Clark and Sheffield. Hamburger King moved across the street in about 1968. We ourselves lived just a few blocks away at 3517 N. Racine.

“Some of the things I remember about Hamburger King:

“1) The time my father chased a customer with a frying pan turner out to the street, when he called another customer—Andy Lee—a ‘stupid chink.’ Andy was a Chinese American guy who used to eat at the restaurant frequently.

“2) There used to be a connecting door between Hamburger King and the Nisei Lounge. Whenever the Hamburger King was full, customers would go through the door to Nisei and order their food. My mom didn’t like me to wait on customers in a bar, let alone a bar with a pool table, but hey, it provided another 20+ seats!

“3) The old‐time Chicago Cubs of the 1970s—some of them would eat breakfast at our Dad’s place, before heading off to batting practice before a day game.

“4) The ‘famous’ special dish called the Akutagawa, after George Akutagawa, who was a frequent customer. This was his favorite dish. It consisted of ground hamburger, bean sprouts, eggs, and onions all mixed together on a flat top grill and served with rice. It’s still on the menu of the current restaurant located at 3435 N. Sheffield, as is a noodle dish called Yet Ca Mein.

“5) Except for the hamburgers and grilled cheese, just about everything on the menu could be ordered with rice—Polish sausage, eggs and rice; bacon and eggs and rice; flank steak and rice; pork chops and rice; chili mac and rice; and of course, rice and gravy.”

—Emi Yamauchi, former resident/daughter of Hamburger King proprieter Thomas Yamauchi

“My father, Thomas Yamauchi, was owner of the Hamburger King. He had a partner who had to drop out of the partnership. I worked as a dishwasher sometimes on the weekends during the late 1960s, early 1970s, and my sisters were waitresses from then until the early 1980s.

“I also worked in Nisei Lounge the summer of 1985, which was a great experience seeing and talking to many Japanese Americans who are no longer with us, but who were from the mainland and Hawaii!

“For me, both the Hamburger King and Nisei Lounge (they were connected together by a common door!) played important cultural and social roles for the Japanese American community in Chicago from the early 1950s until the 1990s. Lots of friendships and social activities sprung from the duo!”

—Paul Yamauchi, former resident/son of Hamburger King proprietor Thomas Yamauchi

* * * * *

853 W. Belmont (Toguri Mercantile, 2nd Floor)

(Map Item #41)

Shojiro Sugiyama

Current status: Extant, as of 2014, under new management, at 1016 W. Belmont (Japanese Culture Center).

Photo courtesy of the author.

“Growing up at 1025 W. Wolfram (one block north of Diversey and one block west of Sheffield) was GREAT. If you had nothing to do, you’d just have to wait in the ‘playground’ and someone would show up.

“The ‘playground’ was the school yard of Agassiz elementary school. A very small, one room 15' x 15', building, housed the playground supervisors and attendant. Tom Hoffman for the boys, Ms. Abe for the girls, and Big George was the attendant.

“Tom Hoffman used his personal cars to ferry the boys to softball (16" Chicago softball), basketball, volleyball, football, horseshoes, track, even ping pong. Needless to say, with as many as ten boys in his car, we trashed his cars.

“We won the Brentano Open Flag Football Championship five years in a row, along with many softball championship from Wells Park and Kosciusko Park. We lost the DePaul Settlement House basketball championship because there was a rumor that the other team was going to beat us up if we won.

“Once, Tom took us on an overnight ‘camping’ trip. One guy wouldn’t sleep outside and we filled the car with lightning bugs.

“Ms. Abe didn’t drive so the girls had to walk to all their events.

“In the winter, they flooded the playground for ice skating. One time we were playing ‘crack the whip’ and flung Alan Oshita into a post and knocked out his two front teeth.

“Parents were never involved in any of our activities.

“Jack Nakanishi, his sister Judy, and younger brother Kenny and Alan Oshita were the Agassiz Japanese. Ben Sakuma was the Barry Street Japanese boy and ‘Mugs’ was a Wrightwood Japanese guy. I came to know many more Japanese at Waller High School.

“The equipment available and the staff were provided by the Chicago Park District.

“Our boundaries were Diversey and Oakdale to the south and north and Sheffield to Racine, east to west.

“In those days, we would ride our bikes (some had only one pedal and no one had helmets) down Diversey to the Lake to fish at Diversey harbor. We could go to a Cub game and get in after the seventh inning for free and clean up and get a ticket for the next game. That’s when they had Hall of Famers, Ernie Banks, Ron Santo, Fergie Jenkins, Billy Williams, and the likes of Glenn Beckett, Don Elston, Dick Ellsworth, Ken Hubbs, Bob Will, and made the infamous trade of Lou Brock.

“We even went to the 1963 Bears/Giants Championship game at Wrigley Field, where the Bears played their home games. I was standing in the second tier aisle when the Champion Chicago Bears went off the field to their locker room along the left field line. I went down closer to see the players come off the field and low and behold, Ed O’Bradovich, the Bears DE threw his helmet into the stands right where I had been standing.

“I’d say the neighborhood was lower middle class, but no one felt it. We were just happy. We had an apartment, food, and clothes.

“I think my parents could have bought the two flat with a coach house for $15,000. It had the BEST back yard for catch night crawlers. Hundreds of them.

“Those were the days.”

—Bruce Matsunaga, former resident

|

CLARK STREET

BELMONT AVENUE

SHEFFIELD AVENUE

HALSTED STREET

BROADWAY STREET

RACINE AVENUE

SOUTHPORT AVENUE

ASHLAND AVENUE

|

* The author wishes to express special thanks to the following for their extraordinary support and encouragement in this project:

Karen Kanemoto: Manager, Japanese American Service Committee Legacy Center Archives

Michael Takada: Chief Executive Officer, Japanese American Service Committee

Mary Doi: Board Member, Chicago Japanese American Historical Society

And all of the former residents who offered feedback and recollections.

© 2014 Erik Matsunaga