Japanese American Women and Activism Within the JA Community: Redress, Reparations, and Gender

Japanese American Women and Activism Within the JA Community: Redress, Reparations, and Gender

Civil Liberties Act of 1988 - Victory!

When President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 on August 10th, it marked a day of victory, finally, for the Japanese American community and all those who had been so invested in the Redress and Reparations campaign. The hours and hours of work everyone had contributed were instantaneously completely justified. It was all worth it.

Tears of joy were wept, and inexpressible happiness and relief filled that room when Reagan signed the bill. It was indeed, a momentous occasion for Japanese Americans who gave their all to this cause. Sox Kitashima recalls that “the community was on cloud nine and ready to burst.” (95)

To address gender, notice that there is only one woman in this picture. Although the Japanese American community and the Redress/Reparations movement are no exception to being in situations where women are underrepresented in politics and head positions at the federal level, it is worthwhile to be aware of the existence of such dynamics. Also of notable presence in this picture are Congressmen Norman Mineta and Robert T. Matsui, two men who, with the complementary work of others like Sox, Aiko, Cherry and Lorraine, were instrumental in the signing and passage of this bill.

Source: Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003 (pp. 92-95)

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Kinoshita Collection

--

When President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 on August 10th, it marked a day of victory, finally, for the Japanese American community and all those who had been so invested in the Redress and Reparations campaign. The hours and hours of work everyone had contributed were instantaneously completely justified. It was all worth it.

Tears of joy were wept, and inexpressible happiness and relief filled that room when Reagan signed the bill. It was indeed, a momentous occasion for Japanese Americans who gave their all to this cause. Sox Kitashima recalls that “the community was on cloud nine and ready to burst.” (95)

To address gender, notice that there is only one woman in this picture. Although the Japanese American community and the Redress/Reparations movement are no exception to being in situations where women are underrepresented in politics and head positions at the federal level, it is worthwhile to be aware of the existence of such dynamics. Also of notable presence in this picture are Congressmen Norman Mineta and Robert T. Matsui, two men who, with the complementary work of others like Sox, Aiko, Cherry and Lorraine, were instrumental in the signing and passage of this bill.

Source: Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003 (pp. 92-95)

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Kinoshita Collection

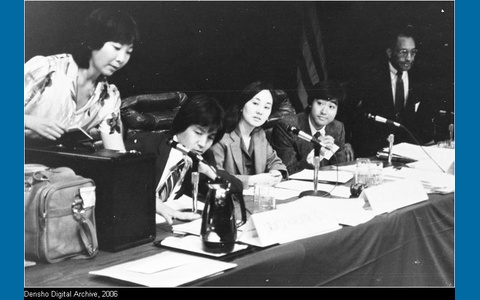

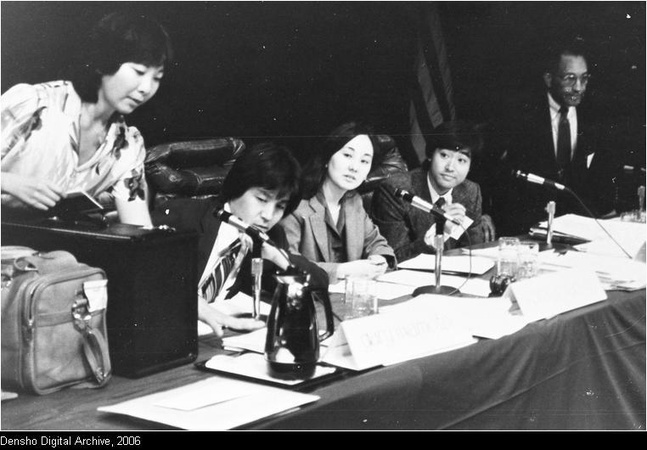

Redress Hearings

The Redress hearings put on by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) created by President Jimmy Carter were a chance for internees to appeal to the government-appointed entity and have the looming issues of Internment and Redress be remedied accordingly. As both Sox Kitashima and Cherry Kinoshita recalled, it was a very emotional time for many.

Sox was both overwhelmed and inspired by the sheer number of people that came out to these hearings to speak. Counted at over six hundred, Sox also spoke at these hearings, of her difficult and dehumanizing experiences as a result of Executive Order 9066 and subsequent internment she had to live through.

The emotional and psychological pain that these internees suffered also came through for Cherry Kinoshita, who also spoke at the hearings. It was a realization for her, that the tragedy that she and others experienced was very deep – to have the irreversible disruption of everyday life affect you and define you for the remainder of your years.

These hearings were the very beginning steps forward for the Redress and Reparations campaign, and also the beginning of involvement for Cherry and Sox.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collections: Densho Visual History Collection, Cherry Kinoshita Interviews; Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: National Archives and Records Administration Collection.

--

The Redress hearings put on by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) created by President Jimmy Carter were a chance for internees to appeal to the government-appointed entity and have the looming issues of Internment and Redress be remedied accordingly. As both Sox Kitashima and Cherry Kinoshita recalled, it was a very emotional time for many.

Sox was both overwhelmed and inspired by the sheer number of people that came out to these hearings to speak. Counted at over six hundred, Sox also spoke at these hearings, of her difficult and dehumanizing experiences as a result of Executive Order 9066 and subsequent internment she had to live through.

The emotional and psychological pain that these internees suffered also came through for Cherry Kinoshita, who also spoke at the hearings. It was a realization for her, that the tragedy that she and others experienced was very deep – to have the irreversible disruption of everyday life affect you and define you for the remainder of your years.

These hearings were the very beginning steps forward for the Redress and Reparations campaign, and also the beginning of involvement for Cherry and Sox.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collections: Densho Visual History Collection, Cherry Kinoshita Interviews; Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: National Archives and Records Administration Collection.

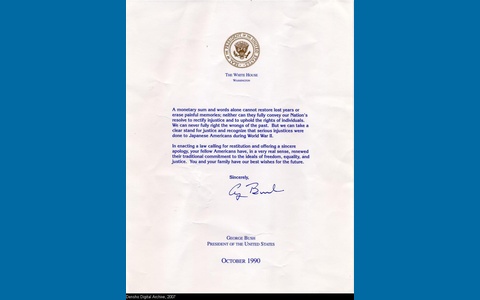

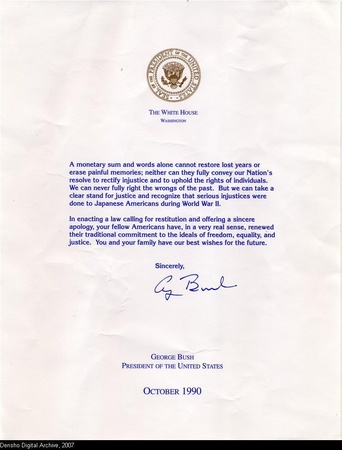

Official Apology from the United States Government

In October of 1990, George Bush signed this official apology to the Japanese American internees and their families for the pain and hardship they had suffered during and after World War II due to Internment.

This apology followed the signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, the marked victory of the Redress and Reparations Campaign that these four women were so heavily involved in. It is another achievement that they very much helped to attain, as the government was proven to be unquestionably responsible for a dire violation of civil liberties of Japanese American citizens, and following the issuance of redress, also included a written apology for these actions.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Manzanar Historical Site Collection.

--

In October of 1990, George Bush signed this official apology to the Japanese American internees and their families for the pain and hardship they had suffered during and after World War II due to Internment.

This apology followed the signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, the marked victory of the Redress and Reparations Campaign that these four women were so heavily involved in. It is another achievement that they very much helped to attain, as the government was proven to be unquestionably responsible for a dire violation of civil liberties of Japanese American citizens, and following the issuance of redress, also included a written apology for these actions.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Manzanar Historical Site Collection.

--

In October of 1990, George Bush signed this official apology to the Japanese American internees and their families for the pain and hardship they had suffered during and after World War II due to Internment.

This apology followed the signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, the marked victory of the Redress and Reparations Campaign that these four women were so heavily involved in. It is another achievement that they very much helped to attain, as the government was proven to be unquestionably responsible for a dire violation of civil liberties of Japanese American citizens, and following the issuance of redress, also included a written apology for these actions.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Manzanar Historical Site Collection.

Cherry Kinoshita receives Jefferson Award

This article features Cherry Kinoshita in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Reporter, as she is awarded for her efforts in the Redress and Reparations movement. As recognition for the significant work that she carried out in making the acquisition of justice a reality for the Japanese American community, this is proof that what she did was very important to the campaign.

However, in reading her responses to the article, she attributes much of her success to others, rather than spotlighting herself in the matter. This kind of a reaction to her award can be a mix of many things, namely humility, refusal to take credit alone for work that many carried out, perhaps gender-related cultural tendencies, and the want to acknowledge those who did make her efforts possible.

But Cherry’s situation aside, it is reactions and attitudes like these that are also common of Japanese American women, especially Isseis and Niseis, where they do not want to receive lots of attention for any particular occurrence or action. Rather, they would prefer to stay in the background and be somewhat invisible to the public eye. Drawing this sort of attention to oneself can be looked upon as distasteful to some who value that role for women as the domestic, obedient sex.

Nevertheless, it is very well that this article should recognize and applaud her efforts in the Redress movement, while also publicizing her achievements. There should be more articles and publications of this sort to acknowledge, without embarrassing, these women for their amazing accomplishments.

Source: Seattle Post Website, http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/local/163082_kinoshita04.html

--

This article features Cherry Kinoshita in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Reporter, as she is awarded for her efforts in the Redress and Reparations movement. As recognition for the significant work that she carried out in making the acquisition of justice a reality for the Japanese American community, this is proof that what she did was very important to the campaign.

However, in reading her responses to the article, she attributes much of her success to others, rather than spotlighting herself in the matter. This kind of a reaction to her award can be a mix of many things, namely humility, refusal to take credit alone for work that many carried out, perhaps gender-related cultural tendencies, and the want to acknowledge those who did make her efforts possible.

But Cherry’s situation aside, it is reactions and attitudes like these that are also common of Japanese American women, especially Isseis and Niseis, where they do not want to receive lots of attention for any particular occurrence or action. Rather, they would prefer to stay in the background and be somewhat invisible to the public eye. Drawing this sort of attention to oneself can be looked upon as distasteful to some who value that role for women as the domestic, obedient sex.

Nevertheless, it is very well that this article should recognize and applaud her efforts in the Redress movement, while also publicizing her achievements. There should be more articles and publications of this sort to acknowledge, without embarrassing, these women for their amazing accomplishments.

Source: Seattle Post Website, http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/local/163082_kinoshita04.html

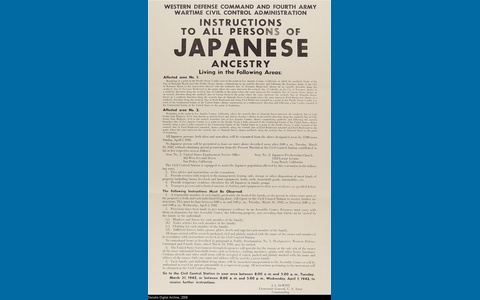

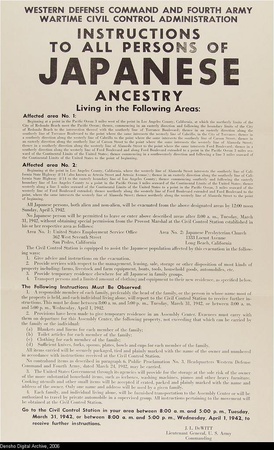

Notice of Relocation

This was the notice posted all over the West Coast preceding the immediate removal of over 110,000 Japanese Americans from their homes and into internment camps. They had only a few weeks to pack what they could carry, most often in one or two suitcases, and find a way to either sell, or place in someone else's care, the rest of their property.

Cherry Kinoshita, Sox Kitashima, and Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig all recalled painful memories of having to leave everything behind for a life in barracks that had no decent accommodations. For Sox, it was especially painful to succumb to inedible foods, when earlier in the day, she had just had a wonderful, home-cooked meal. Aiko similarly remembers the terrible mess hall foods they were served, where camps even competed to see who could spend the least on expenses for internees. These “costs” went as low as $.35 per person!

An indication of the real struggles to come after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, this picture is representative of the hardships that not only these women, but the entire Japanese American community faced in this wartime era.

Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collections: Densho Visual History Collection, Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig Interviews; Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: The Manuscripts, Special collections, University Archives Division, University of Washington Libraries Collection.

--

This was the notice posted all over the West Coast preceding the immediate removal of over 110,000 Japanese Americans from their homes and into internment camps. They had only a few weeks to pack what they could carry, most often in one or two suitcases, and find a way to either sell, or place in someone else's care, the rest of their property.

Cherry Kinoshita, Sox Kitashima, and Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig all recalled painful memories of having to leave everything behind for a life in barracks that had no decent accommodations. For Sox, it was especially painful to succumb to inedible foods, when earlier in the day, she had just had a wonderful, home-cooked meal. Aiko similarly remembers the terrible mess hall foods they were served, where camps even competed to see who could spend the least on expenses for internees. These “costs” went as low as $.35 per person!

An indication of the real struggles to come after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, this picture is representative of the hardships that not only these women, but the entire Japanese American community faced in this wartime era.

Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collections: Densho Visual History Collection, Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig Interviews; Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: The Manuscripts, Special collections, University Archives Division, University of Washington Libraries Collection.

The Beginnings of Activism: Influences and Inspirations

During the late 1960s and 1970s, America was experiencing a time of enormous social change and upheaval. The Vietnam War, Civil Rights Movement, the rise of Black Power, and other revolutionary occurrences were changing the way people thought about race, gender, sexuality, political freedom, and civil liberties.

Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig herself was involved in the activism of the 70s, partaking regularly in Asian American for Action rallies and events, including protests against the Vietnam War. It was within this organization that she honed her political awareness and progressivism, as she watched the events surrounding the Vietnam War and realized the importance of challenging authority in the face of injustices. During one of the protests a press photographer captured her chanting and marching with everyone else, and her pictures showed up in the newspaper the next day. Anticipating displeasure from her family, she was not surprised when they commented unhappily about her being the “black sheep of the family, involving [her]self in activities that would be frowned upon by the rest of the community, most likely.” Her sister commented also on the kinds of reactions she might receive from her peers and the rest of the community, who would equally disprove of participating in such a ruckus.

This kind of “quiet pressure,” as Aiko calls it, was and often still is characteristic of the beliefs and traditions of the Japanese American Issei and Nisei generations. Relating to the “shikata ga nai” value, which dictates that one cannot help situations and should leave them be, many JAs do not believe in creating trouble, much less challenging authority on matters such as these. But regardless of cultural and traditional pressures, Aiko took a liking to sorting out and fighting for political injustices and human rights violations.

Similarly, being in an era of such movement around civil and human rights issues at a young age had an influence on Lorraine Bannai. Although not as pressured by family as Aiko might have been because of generational differences and being raised in different times, Lorraine knew that her parents might still be concerned. Still, Lorraine continued to be increasingly aware of the political activism happening around her, and recalls vividly those times of significant social change.

Both of these women were definitely a product of their times, where the activism that happened in larger society began to shape their own consciousness about the injustices in their own communities.

Source:Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collections: Densho Visual History Collection: Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig Interviews, Segment 2 and Lorraine Bannai Interviews, Segment 11.

Photo: Online Archive of California, http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf8b69p0d4/?&query;=Vietnam%20war%20protest&brand;=oac.

--

During the late 1960s and 1970s, America was experiencing a time of enormous social change and upheaval. The Vietnam War, Civil Rights Movement, the rise of Black Power, and other revolutionary occurrences were changing the way people thought about race, gender, sexuality, political freedom, and civil liberties.

Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig herself was involved in the activism of the 70s, partaking regularly in Asian American for Action rallies and events, including protests against the Vietnam War. It was within this organization that she honed her political awareness and progressivism, as she watched the events surrounding the Vietnam War and realized the importance of challenging authority in the face of injustices. During one of the protests a press photographer captured her chanting and marching with everyone else, and her pictures showed up in the newspaper the next day. Anticipating displeasure from her family, she was not surprised when they commented unhappily about her being the “black sheep of the family, involving [her]self in activities that would be frowned upon by the rest of the community, most likely.” Her sister commented also on the kinds of reactions she might receive from her peers and the rest of the community, who would equally disprove of participating in such a ruckus.

This kind of “quiet pressure,” as Aiko calls it, was and often still is characteristic of the beliefs and traditions of the Japanese American Issei and Nisei generations. Relating to the “shikata ga nai” value, which dictates that one cannot help situations and should leave them be, many JAs do not believe in creating trouble, much less challenging authority on matters such as these. But regardless of cultural and traditional pressures, Aiko took a liking to sorting out and fighting for political injustices and human rights violations.

Similarly, being in an era of such movement around civil and human rights issues at a young age had an influence on Lorraine Bannai. Although not as pressured by family as Aiko might have been because of generational differences and being raised in different times, Lorraine knew that her parents might still be concerned. Still, Lorraine continued to be increasingly aware of the political activism happening around her, and recalls vividly those times of significant social change.

Both of these women were definitely a product of their times, where the activism that happened in larger society began to shape their own consciousness about the injustices in their own communities.

Source:Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collections: Densho Visual History Collection: Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig Interviews, Segment 2 and Lorraine Bannai Interviews, Segment 11.

Photo: Online Archive of California, http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf8b69p0d4/?&query;=Vietnam%20war%20protest&brand;=oac.

Lorraine Bannai, Introduction

As a Sansei born in Gardena, California in 1955, Lorraine Bannai had a somewhat different experience in the Redress and Reparations movement. Too young to have experienced the camps, Lorraine became aware of Japanese American history both through her family, and her experiences in school. She had a keen consciousness about her identity as a Japanese American, and as a person of color, seemingly cultivated by the unusually prominent demographic of Japanese Americans in the neighborhood where she was raised.

In her interview, Lorraine expresses very affectionate feelings towards her grandparents, both paternal and maternal, who, both through discussion and action alone, showed her the ways of Japanese American tradition and values. Her mother was also a strong role model figure in her life, one who inspired Lorraine to pursue her desires despite what others thought. Although she could not speak Japanese, by observing those around her she grew up with a thorough understanding of what it meant to be JA.

In junior high school, she was surrounded by events like the Vietnam War protests and those stemming from later phases of the Civil Rights Movement, all of which sparked the beginnings of progressivism in Lorraine’s mind. Entering law school further expanded this consciousness, concerning race and political activism, where she directly participated in rallies around such issues as Affirmative Action.

With the reopening of the Fred Korematsu case in 1983, Lorraine, now a newly accredited attorney, joined the team and was a part of the victory that ended up in this coram nobis case having the original conviction vacated. Amidst her legal experiences, Lorraine was also aware of her own position as an Asian American woman, and the external perceptions of pertaining to race and gender combined. She felt that others would judge her as the quiet stereotype, and oftentimes was assumed to be a clerk or a recorder, not an attorney. Obviously, by people, both of color and white, made assumptions about her race and gender. So she put forth the extra effort to ensure that she proved them wrong.

But when questioned about how gender played out in the wider processes involved in Redress and Reparations and the coram nobis cases, Lorraine did not give an answer, indicating she was not able to formulate a proper response she would be comfortable with. This is indicative of the attitudes and perspectives of the other three Japanese American women as well, as although it seems they were often aware of their own gender and/or race and how it affected their own position in contexts outside of the Japanese American community, they were not as conscious of how gender was perceived in areas like Redress, where the JA community worked so closely together.

Still, Lorraine’s experiences as a Sansei show a more complex, developed awareness about issues of race, social justice and activism that came about in her years, also indicating the difference that generation can make in the attitudes that are adopted about these matters according to time. This point of view also led her to constantly surround herself with like-minded people that she was able to learn from. Additionally, that perspective that she was able to bring to the table in the Korematsu case shaped her as a very qualified and instrumental Japanese American woman whose contributions were necessary for the vacation of that conviction. And of course, without those coram nobis cases, Redress would not have been possible.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collections: Densho Visual History Collection, Lorraine Bannai Interviews.

--

As a Sansei born in Gardena, California in 1955, Lorraine Bannai had a somewhat different experience in the Redress and Reparations movement. Too young to have experienced the camps, Lorraine became aware of Japanese American history both through her family, and her experiences in school. She had a keen consciousness about her identity as a Japanese American, and as a person of color, seemingly cultivated by the unusually prominent demographic of Japanese Americans in the neighborhood where she was raised.

In her interview, Lorraine expresses very affectionate feelings towards her grandparents, both paternal and maternal, who, both through discussion and action alone, showed her the ways of Japanese American tradition and values. Her mother was also a strong role model figure in her life, one who inspired Lorraine to pursue her desires despite what others thought. Although she could not speak Japanese, by observing those around her she grew up with a thorough understanding of what it meant to be JA.

In junior high school, she was surrounded by events like the Vietnam War protests and those stemming from later phases of the Civil Rights Movement, all of which sparked the beginnings of progressivism in Lorraine’s mind. Entering law school further expanded this consciousness, concerning race and political activism, where she directly participated in rallies around such issues as Affirmative Action.

With the reopening of the Fred Korematsu case in 1983, Lorraine, now a newly accredited attorney, joined the team and was a part of the victory that ended up in this coram nobis case having the original conviction vacated. Amidst her legal experiences, Lorraine was also aware of her own position as an Asian American woman, and the external perceptions of pertaining to race and gender combined. She felt that others would judge her as the quiet stereotype, and oftentimes was assumed to be a clerk or a recorder, not an attorney. Obviously, by people, both of color and white, made assumptions about her race and gender. So she put forth the extra effort to ensure that she proved them wrong.

But when questioned about how gender played out in the wider processes involved in Redress and Reparations and the coram nobis cases, Lorraine did not give an answer, indicating she was not able to formulate a proper response she would be comfortable with. This is indicative of the attitudes and perspectives of the other three Japanese American women as well, as although it seems they were often aware of their own gender and/or race and how it affected their own position in contexts outside of the Japanese American community, they were not as conscious of how gender was perceived in areas like Redress, where the JA community worked so closely together.

Still, Lorraine’s experiences as a Sansei show a more complex, developed awareness about issues of race, social justice and activism that came about in her years, also indicating the difference that generation can make in the attitudes that are adopted about these matters according to time. This point of view also led her to constantly surround herself with like-minded people that she was able to learn from. Additionally, that perspective that she was able to bring to the table in the Korematsu case shaped her as a very qualified and instrumental Japanese American woman whose contributions were necessary for the vacation of that conviction. And of course, without those coram nobis cases, Redress would not have been possible.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collections: Densho Visual History Collection, Lorraine Bannai Interviews.

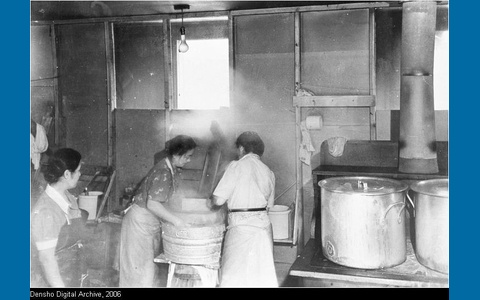

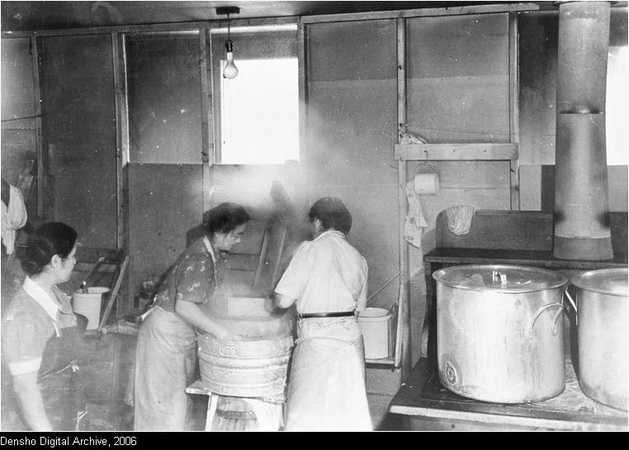

Overview: Gender Roles within the Japanese American Community – an Analysis

Shown above is a photo of women carrying out domestic work (i.e. laundry, cooking) at the Minidoka concentration camp in 1943, where Cherry Kinoshita was interned. Analysis of the Japanese American experience starting from the Issei reveals the kinds of gender roles that were ascribed from the very beginning to promote assimilation into American society.

That is, in adopting the American way of life to become accepted within their new country, Japanese Americans needed to prove themselves as worthy, non-inferior people of color. Culturally-related activities, such as folk dancing, tea ceremony, or flower arrangement were reserved for women, while men participated in matters of politics and state (179). Additionally, to be perceived by white American society as acceptable, women were groomed to be quiet, domestic, and obedient according to American middle-class standards. They were often even exotified as possessing such qualities, and used for the benefit of the community in its entirety.

While women stayed in the domestic sphere, as Azuma states, “their husbands tackled the more public dimension of racial politics, like propaganda, court battles, and economic struggles” (8). These gender roles continued most visibly into the Redress and Reparations era.

Japanese American men had been elected into political offices on both local and national levels, while women in the community stayed behind to take care of matters on a more grassroots level. Presidents of organizations like the Japanese American Citizens League and the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations at the time were men as well, and women did the letter sending, participated in lobbying, and stayed away from the limelight most of the time.

But this combination of Japanese American culture/values, and the need for first generation Japanese immigrants to assimilate into American society dictated this situation for both men and women. In looking at the experiences and works of Sox Kitashima, Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig, Cherry Kinoshita, and Lorraine Bannai, we can both see the gender-affected roles each played in the Redress/Reparations movement and the effects of generational influences on the types of work carried out in the campaign.

Source: Azuma, Eiichiro, Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Photo: Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Wing Luke Asian Museum Collection.

--

Shown above is a photo of women carrying out domestic work (i.e. laundry, cooking) at the Minidoka concentration camp in 1943, where Cherry Kinoshita was interned. Analysis of the Japanese American experience starting from the Issei reveals the kinds of gender roles that were ascribed from the very beginning to promote assimilation into American society.

That is, in adopting the American way of life to become accepted within their new country, Japanese Americans needed to prove themselves as worthy, non-inferior people of color. Culturally-related activities, such as folk dancing, tea ceremony, or flower arrangement were reserved for women, while men participated in matters of politics and state (179). Additionally, to be perceived by white American society as acceptable, women were groomed to be quiet, domestic, and obedient according to American middle-class standards. They were often even exotified as possessing such qualities, and used for the benefit of the community in its entirety.

While women stayed in the domestic sphere, as Azuma states, “their husbands tackled the more public dimension of racial politics, like propaganda, court battles, and economic struggles” (8). These gender roles continued most visibly into the Redress and Reparations era.

Japanese American men had been elected into political offices on both local and national levels, while women in the community stayed behind to take care of matters on a more grassroots level. Presidents of organizations like the Japanese American Citizens League and the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations at the time were men as well, and women did the letter sending, participated in lobbying, and stayed away from the limelight most of the time.

But this combination of Japanese American culture/values, and the need for first generation Japanese immigrants to assimilate into American society dictated this situation for both men and women. In looking at the experiences and works of Sox Kitashima, Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig, Cherry Kinoshita, and Lorraine Bannai, we can both see the gender-affected roles each played in the Redress/Reparations movement and the effects of generational influences on the types of work carried out in the campaign.

Source: Azuma, Eiichiro, Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Photo: Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Wing Luke Asian Museum Collection.

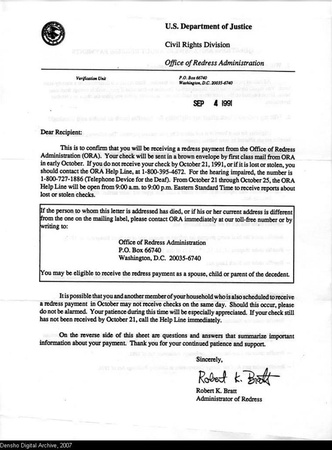

Redress Confirmation Letter

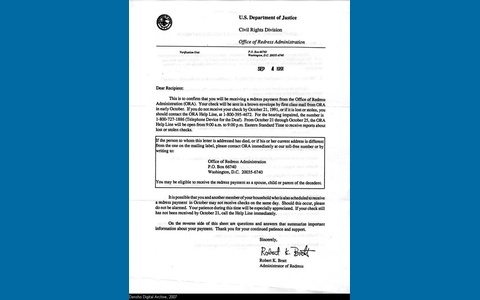

When Japanese Americans who were eligible applied for redress, they received this letter of confirmation from the Office of Redress Administration (ORA), which was in charge of all matters pertaining to the application process for payment.

Sox Kitashima, for one, was a volunteer who regularly helped eligible former internees or their family members apply for redress and receive proper payment. She advised them and made sure they understood the process and could fill out the application properly.

Because of the Redress and Reparations efforts, and efforts by women like Sox, the Office of Redress Administration operated very efficiently, even providing a Help Line for additional assistance.

Source: Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Manzanar National Historical Site Collection.

--

When Japanese Americans who were eligible applied for redress, they received this letter of confirmation from the Office of Redress Administration (ORA), which was in charge of all matters pertaining to the application process for payment.

Sox Kitashima, for one, was a volunteer who regularly helped eligible former internees or their family members apply for redress and receive proper payment. She advised them and made sure they understood the process and could fill out the application properly.

Because of the Redress and Reparations efforts, and efforts by women like Sox, the Office of Redress Administration operated very efficiently, even providing a Help Line for additional assistance.

Source: Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Manzanar National Historical Site Collection.

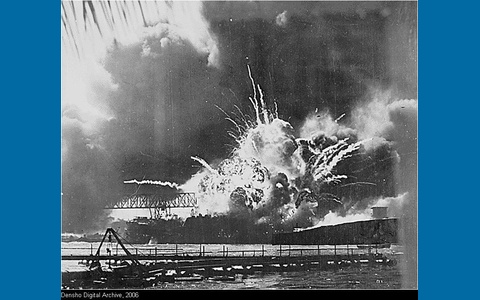

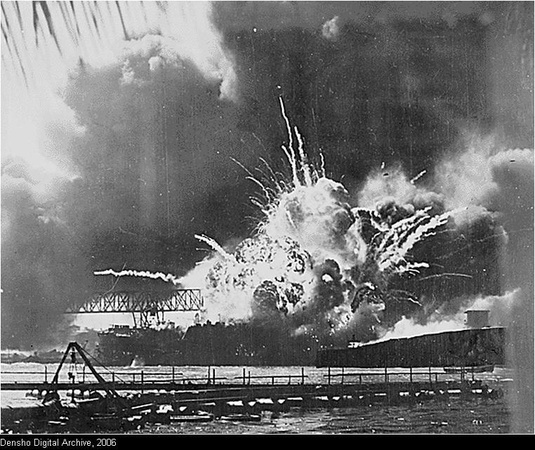

The "Day of Infamy" - a Turning Point for these Women

December 7, 1941 - Japan attacks Pearl Harbor.

This was the beginning of World War II for United States against the Japanese, and marked the beginning of a long struggle for the Japanese American community. For Sox, Aiko, and Cherry - each of them had an experience following the bombing that told them this would not bode well for themselves or their families.

Sox's mother and sister were horrified at the news, keenly aware of the potential consequences to come.

Aiko, a senior in high school, was at a dance when news of the bombing broke. She knew this would trouble, although she could not know how badly it would become.

Cherry was with her father, who was deeply upset by the news, because he knew this would affect the family significantly in the near future.

Lorraine was not born yet, but her parents and grandparents were in the camps because of this day.

The attack on Pearl Harbor gave way to times of racism, discrimination, violations of civil rights not just by non-Japanese Americans but actually brought about by the United States government as an institution. Each woman in her own way persevered despite these hardships, and shaped their sufferings and struggles into positive energy to advocate on behalf of their families and others who experienced the wartime era and lived through the difficulties of resettling and reclaiming their lives.

Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx., Visual History Collection: Densho Visual History Collection: Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig, Cherry Kinoshita, and Lorraine Bannai Interviews; Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx., Photo/Document Collections: National Archives and Records Administration Collection.

--

December 7, 1941 - Japan attacks Pearl Harbor.

This was the beginning of World War II for United States against the Japanese, and marked the beginning of a long struggle for the Japanese American community. For Sox, Aiko, and Cherry - each of them had an experience following the bombing that told them this would not bode well for themselves or their families.

Sox's mother and sister were horrified at the news, keenly aware of the potential consequences to come.

Aiko, a senior in high school, was at a dance when news of the bombing broke. She knew this would trouble, although she could not know how badly it would become.

Cherry was with her father, who was deeply upset by the news, because he knew this would affect the family significantly in the near future.

Lorraine was not born yet, but her parents and grandparents were in the camps because of this day.

The attack on Pearl Harbor gave way to times of racism, discrimination, violations of civil rights not just by non-Japanese Americans but actually brought about by the United States government as an institution. Each woman in her own way persevered despite these hardships, and shaped their sufferings and struggles into positive energy to advocate on behalf of their families and others who experienced the wartime era and lived through the difficulties of resettling and reclaiming their lives.

Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx., Visual History Collection: Densho Visual History Collection: Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig, Cherry Kinoshita, and Lorraine Bannai Interviews; Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx., Photo/Document Collections: National Archives and Records Administration Collection.

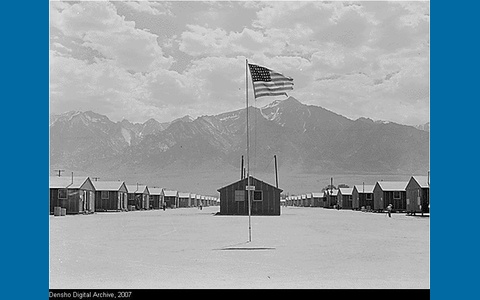

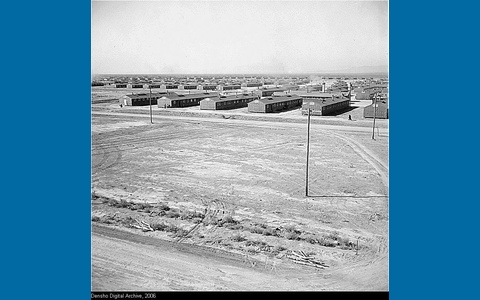

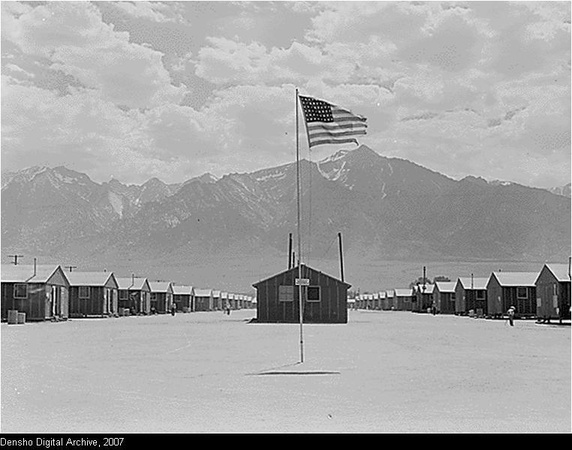

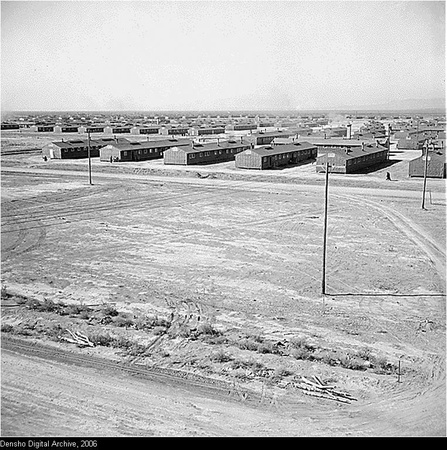

Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig - Internment at Manzanar

Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig and her husband were interned at Manzanar, pictured above, during World War II. This photo beautifully photographed by Ansel Adams captures the scenery of the camp. But such a place holds painful memories for Japanese American internees. In recalling the terrible conditions of camp life, Aiko discussed during one of her interviews the barren environment surrounding the camp. She was shocked at how deserted the area was, with nothing but desert and mountains for miles, and all were often plagued by terrible dust storms and extreme temperatures.

Escape was not an option for internees, she recounts, as armed guard towers aside, there was nowhere to escape to. And as Japanese Americans, they would undoubtedly be very noticeable in any town or village nearby if they did manage to find shelter.

Like Sox, Aiko and Manzanar internees suffered through shortages of food, bad, spoiled, or bland food when they did get to eat, a lack of privacy, no toilet paper in primitive latrines, and hay mattresses. These terrible times are never easy to remember, but it was these kinds of experiences that motivated Aiko to later become involved in Redress to hold the United States government accountable to their unprecedented unconstitutional acts.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collection: Emiko and Chizuko Omori Collection: Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig Interviews, Segments 8, 9, and 14.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Ansel Adams Collection.

--

Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig and her husband were interned at Manzanar, pictured above, during World War II. This photo beautifully photographed by Ansel Adams captures the scenery of the camp. But such a place holds painful memories for Japanese American internees. In recalling the terrible conditions of camp life, Aiko discussed during one of her interviews the barren environment surrounding the camp. She was shocked at how deserted the area was, with nothing but desert and mountains for miles, and all were often plagued by terrible dust storms and extreme temperatures.

Escape was not an option for internees, she recounts, as armed guard towers aside, there was nowhere to escape to. And as Japanese Americans, they would undoubtedly be very noticeable in any town or village nearby if they did manage to find shelter.

Like Sox, Aiko and Manzanar internees suffered through shortages of food, bad, spoiled, or bland food when they did get to eat, a lack of privacy, no toilet paper in primitive latrines, and hay mattresses. These terrible times are never easy to remember, but it was these kinds of experiences that motivated Aiko to later become involved in Redress to hold the United States government accountable to their unprecedented unconstitutional acts.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collection: Emiko and Chizuko Omori Collection: Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig Interviews, Segments 8, 9, and 14.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Ansel Adams Collection.

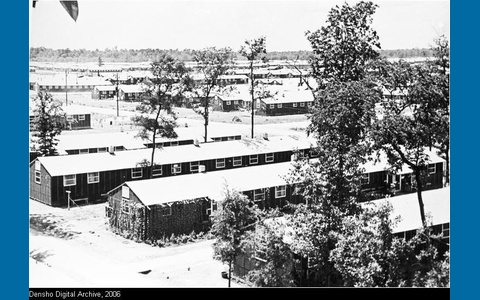

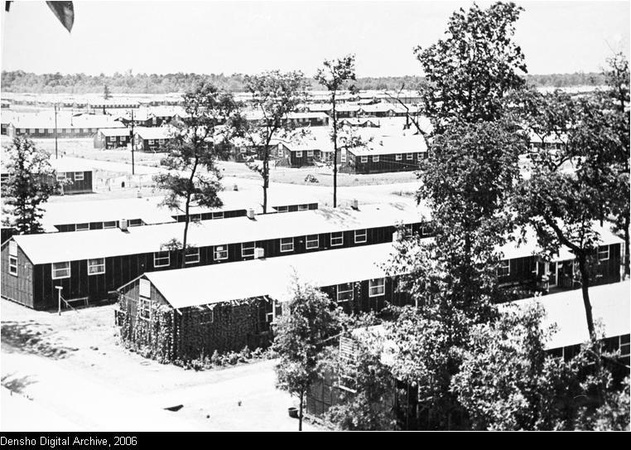

Cherry Kinoshita - Internment at Minidoka

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent signing of Executive Order 9066, Cherry Kinoshita and her family were faced with very difficult circumstances. Like hundreds of thousands of Japanese Americans on the mainland, their lives had changed in a matter of minutes. Her family was questioned by the FBI, and she constantly felt as though everyone suspected her and her family of being in cahoots with the enemy. And when they had to leave everything behind with the exception of what they could carry, their situation only worsened. Cherry and her family were first stationed at Puyallup Assembly Center, then interned at Minidoka, in Idaho, shown in wintertime 1944 in the photo above.

After the war was over, Cherry and her family resettled in the Midwest, and many years later she and her husband returned to her original hometown in Seattle. In the 1970s she became involved with JACL’s Seattle Chapter, and became educated on civil rights issues within the organization. This led to her interest and later, involvement, in the Redress and Reparations campaign.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collection: Densho Visual History Collection: Cherry Kinoshita Interview.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collection: The Manuscripts, Special collections, University Archives Division, University of Washington Libraries Collection.

--

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent signing of Executive Order 9066, Cherry Kinoshita and her family were faced with very difficult circumstances. Like hundreds of thousands of Japanese Americans on the mainland, their lives had changed in a matter of minutes. Her family was questioned by the FBI, and she constantly felt as though everyone suspected her and her family of being in cahoots with the enemy. And when they had to leave everything behind with the exception of what they could carry, their situation only worsened. Cherry and her family were first stationed at Puyallup Assembly Center, then interned at Minidoka, in Idaho, shown in wintertime 1944 in the photo above.

After the war was over, Cherry and her family resettled in the Midwest, and many years later she and her husband returned to her original hometown in Seattle. In the 1970s she became involved with JACL’s Seattle Chapter, and became educated on civil rights issues within the organization. This led to her interest and later, involvement, in the Redress and Reparations campaign.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collection: Densho Visual History Collection: Cherry Kinoshita Interview.

Photo: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collection: The Manuscripts, Special collections, University Archives Division, University of Washington Libraries Collection.

Cherry Kinoshita, Introduction

Cherry Kinoshita was born and raised in Seattle, Washington, and from a very young age took interest in involving herself in leadership-type activities. It started with being president of various organizations in elementary through high school and starting up a newsletter in middle school, then bloomed into involvement with the Redress movement through the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). That early interest in leadership set the stage for the rest of her life, although she did not know it until many years later.

Cherry describes her relationships with both her parents, and her own family, as one of few words. While she was involved with the campaign for Redress, she did not very often speak to her relatives about the issues, or about her work. There were language barriers, and more often things within her family were silently understood.

When Cherry and her family were interned at Minidoka, she had struggled very much alongside the other Japanese Americans on the mainland who suffered the same fate. And following the end of the war, Cherry eventually returned to Seattle, where she became involved in the local JACL chapter. Although she initially joined for social reasons, she eventually became conscious of, and interested in, civil rights issues. This led inevitably to her involvements in the Redress and Reparations movement.

Cherry lobbied in such a way that made her known to legislators in Congress. She was persistent, motivated, and knew exactly what needed to be done to get her point across. She spoke up fearlessly about the JA community’s struggles and needs, and helped ensure the success of the campaign.

Cherry’s experience is very common for Japanese American, Nisei women, in terms of family life, and opinions about how a woman should or should not be. That is, in discussing the campaign, for example, Cherry expressed in an interview with Densho the expressive nature of Nisei women. Women are allowed to show emotion, to be sad or happy, or cry about something, whereas men are not socially allowed this luxury. This “depth of feeling,” as she calls it, is one reserved for women to show, not men.

This perspective on just one gender role is illustrative of the gender dynamics that play out within the JA community, and that were played out during the Redress and Reparations campaign. But while Cherry would cry about her experiences, this same woman also fought courageously to push the Redress bill through Congress. This JA woman helped make history for the Japanese American community, and bring justice where it belonged.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collection: Densho Visual History Collection: Cherry Kinoshita Interview.

--

Cherry Kinoshita was born and raised in Seattle, Washington, and from a very young age took interest in involving herself in leadership-type activities. It started with being president of various organizations in elementary through high school and starting up a newsletter in middle school, then bloomed into involvement with the Redress movement through the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). That early interest in leadership set the stage for the rest of her life, although she did not know it until many years later.

Cherry describes her relationships with both her parents, and her own family, as one of few words. While she was involved with the campaign for Redress, she did not very often speak to her relatives about the issues, or about her work. There were language barriers, and more often things within her family were silently understood.

When Cherry and her family were interned at Minidoka, she had struggled very much alongside the other Japanese Americans on the mainland who suffered the same fate. And following the end of the war, Cherry eventually returned to Seattle, where she became involved in the local JACL chapter. Although she initially joined for social reasons, she eventually became conscious of, and interested in, civil rights issues. This led inevitably to her involvements in the Redress and Reparations movement.

Cherry lobbied in such a way that made her known to legislators in Congress. She was persistent, motivated, and knew exactly what needed to be done to get her point across. She spoke up fearlessly about the JA community’s struggles and needs, and helped ensure the success of the campaign.

Cherry’s experience is very common for Japanese American, Nisei women, in terms of family life, and opinions about how a woman should or should not be. That is, in discussing the campaign, for example, Cherry expressed in an interview with Densho the expressive nature of Nisei women. Women are allowed to show emotion, to be sad or happy, or cry about something, whereas men are not socially allowed this luxury. This “depth of feeling,” as she calls it, is one reserved for women to show, not men.

This perspective on just one gender role is illustrative of the gender dynamics that play out within the JA community, and that were played out during the Redress and Reparations campaign. But while Cherry would cry about her experiences, this same woman also fought courageously to push the Redress bill through Congress. This JA woman helped make history for the Japanese American community, and bring justice where it belonged.

Source: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collection: Densho Visual History Collection: Cherry Kinoshita Interview.

Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig on the coram nobis cases; Lorraine Bannai and Korematsu v. United States

Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig, in an interview with Densho, commented on the importance of the coram nobis cases to passage of the Redress bill. The coram nobis cases consisted of three cases brought by Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Minoru Yasui during World War II to challenge the constitutionality of convictions brought against them for various reasons relating to Internment. Although at the time those convictions were upheld, in 1983 Aiko and a team of Sansei attorneys reopened these cases to have them reheard.

In that same year, all except Min Yasui’s cases were vacated, Yasui being an exception because he passed away before an appeal was possible (83). These coram nobis cases set the stage for questioning the legitimacy and constitutionality of the government’s actions during World War II, and provided an important precedent for the Redress bill. Without these cases, which brought about, for the first time, permeating questions of constitutionality and brought to light many ways in which the government had wronged the JA community, the Redress and Reparations campaign would have taken a different course. Aiko’s efforts to reexamine these cases, without question, made Redress possible.

Above is a brief on one of the coram nobis cases, involving Fred Korematsu, a man who had refused to report for evacuation and as a result was detained for some time at Tanforan Detention Center before going off to camp.

Lorraine Bannai joined the team of lawyers who, in 1981, pursued the reopening of this particular case and succeeded in vacating Korematsu's conviction in 1983. Working closely with Dale Minami, she co-founded the Bay Area Attorneys for Redress group (BAAR), which focused on internment briefs. In this significant way, Lorraine and her group of attorneys contributed to the Redress movement.

[This document is an ASPX document. After downloading the document, open a web browser and in the file menu, choose "Open." Browse for the aspx document and select it to open.]

Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Visual History Collection: Densho Visual History Collection: Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig Interview, Segment 6 and Lorraine Bannai Interview; Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., The Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Document: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collection: Densho Collection.

Sox Kitashima - Internment at Topaz

Following the December 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, Sox Kitashima recalls her mother saying, “This is terrible!” in Japanese (33). This reaction is indicative of her family’s awareness that Japan declaring war on the United States would have a dire effect on the Japanese American community. As Sox recalls, “our way of life changed. Dramatically. Literally overnight we had gone from being Americans to being the ‘enemy.’” (33)

In the days, weeks, and months that followed, Sox and her family were split up, with she and her sister Lillian heading off to Topaz, and her mother and other siblings to Tule Lake. Sox was horrified at the new life that was forced upon them – physical searches, and “discolored cold cuts, overcooked swiss chard, and moldy bread” (79). Forty years later, recalling such memories still brought tears.

Shown here are the barracks at Topaz; this photo was taken in 1942. It was the kind of life Sox experienced at Topaz that motivated her to take on the Redress and Reparations endeavor, and dedicated her so to the cause.

Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: National Archives and Records Administration Collection.; Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

--

Following the December 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, Sox Kitashima recalls her mother saying, “This is terrible!” in Japanese (33). This reaction is indicative of her family’s awareness that Japan declaring war on the United States would have a dire effect on the Japanese American community. As Sox recalls, “our way of life changed. Dramatically. Literally overnight we had gone from being Americans to being the ‘enemy.’” (33)

In the days, weeks, and months that followed, Sox and her family were split up, with she and her sister Lillian heading off to Topaz, and her mother and other siblings to Tule Lake. Sox was horrified at the new life that was forced upon them – physical searches, and “discolored cold cuts, overcooked swiss chard, and moldy bread” (79). Forty years later, recalling such memories still brought tears.

Shown here are the barracks at Topaz; this photo was taken in 1942. It was the kind of life Sox experienced at Topaz that motivated her to take on the Redress and Reparations endeavor, and dedicated her so to the cause.

Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: National Archives and Records Administration Collection.; Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

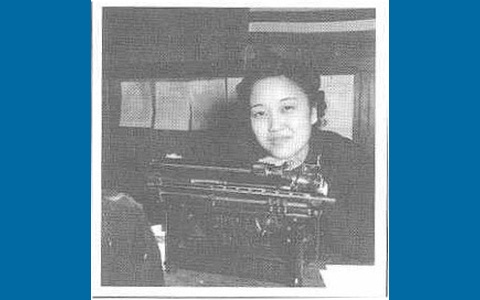

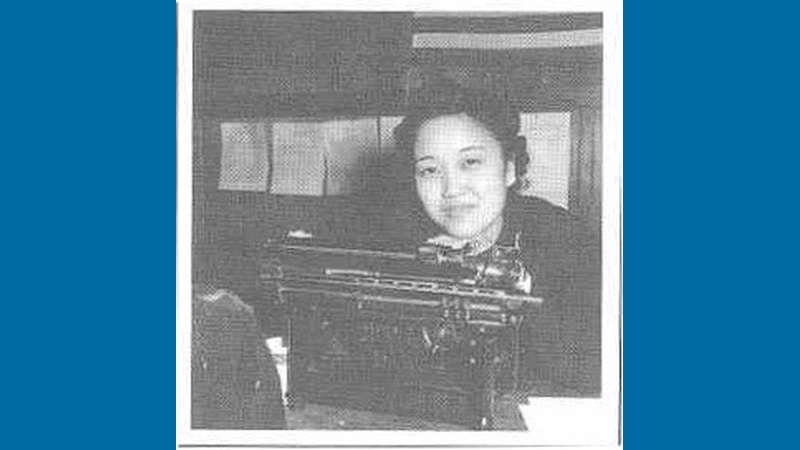

Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig, Introduction

Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig is most well known for her archiving work during the Redress and Reparations movement of the 1980s. Interned at the Manzanar Incarceration Camp during World War II, Aiko spent a few years there, fully experiencing the positives and negatives and dangers of camp life. Many years later in the 1970s, Aiko involved herself with Asian Americans for Action, an organization dedicated to progressive movement and issues within the Asian American community. As a part of AAA activism, Aiko participated in protests for the Vietnam War, among other things. This was a starting point for her deep involvement in important political issues affecting her and the community around her.

After marrying and settling down, Aiko took an interest in the National Archives. She began to look through documents pertaining to the incarceration of JAs, since she and her family had spent time in the camps. Her search for files the government kept on herself and her family eventually branched out into looking for files and documents pertaining to Internment. As she found relevant and pertinent documents, she began to build a separate archive for this particular topic. And as the Redress and Reparations movement was set into motion in the late 1970s and 1980s, Aiko’s finds became increasingly revealing. She dug up documents that proved, without question, the racist nature of Internment and the government’s knowledge of the illegitimacy of such actions. As mentioned in Fujita-Rony’s article, her very meticulous archiving skills made her a “destructive force” to be reckoned with; the government did not stand a chance against all the damning information she had found and collected.

Despite Japanese American traditions according to gender, which dictated that a woman’s place was most often in the home with her family, women like Aiko stepped up to the plate and contributed most significantly to the Redress and Reparations movement. Although the work that she did was not at the forefront or very involved with the direct political process as many of the men were, because of the crucial documents she found that made their case virtually bulletproof, thousands of Japanese Americans who had suffered in the camps were compensated with $20,000 in payments. Her significant contributions to the movement and accomplishments of Redress and Reparations are incredibly important, and should be publicized so that she can receive proper recognition for her work.

Sources: The Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx (Visual History Collections: Densho Visual History Collection: Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig), and Fujita-Rony, Tony, "Destructive Force." Vol 24., No. 1, Frontiers Publication, 2003.

--

Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig is most well known for her archiving work during the Redress and Reparations movement of the 1980s. Interned at the Manzanar Incarceration Camp during World War II, Aiko spent a few years there, fully experiencing the positives and negatives and dangers of camp life. Many years later in the 1970s, Aiko involved herself with Asian Americans for Action, an organization dedicated to progressive movement and issues within the Asian American community. As a part of AAA activism, Aiko participated in protests for the Vietnam War, among other things. This was a starting point for her deep involvement in important political issues affecting her and the community around her.

After marrying and settling down, Aiko took an interest in the National Archives. She began to look through documents pertaining to the incarceration of JAs, since she and her family had spent time in the camps. Her search for files the government kept on herself and her family eventually branched out into looking for files and documents pertaining to Internment. As she found relevant and pertinent documents, she began to build a separate archive for this particular topic. And as the Redress and Reparations movement was set into motion in the late 1970s and 1980s, Aiko’s finds became increasingly revealing. She dug up documents that proved, without question, the racist nature of Internment and the government’s knowledge of the illegitimacy of such actions. As mentioned in Fujita-Rony’s article, her very meticulous archiving skills made her a “destructive force” to be reckoned with; the government did not stand a chance against all the damning information she had found and collected.

Despite Japanese American traditions according to gender, which dictated that a woman’s place was most often in the home with her family, women like Aiko stepped up to the plate and contributed most significantly to the Redress and Reparations movement. Although the work that she did was not at the forefront or very involved with the direct political process as many of the men were, because of the crucial documents she found that made their case virtually bulletproof, thousands of Japanese Americans who had suffered in the camps were compensated with $20,000 in payments. Her significant contributions to the movement and accomplishments of Redress and Reparations are incredibly important, and should be publicized so that she can receive proper recognition for her work.

Sources: The Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx (Visual History Collections: Densho Visual History Collection: Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig), and Fujita-Rony, Tony, "Destructive Force." Vol 24., No. 1, Frontiers Publication, 2003.

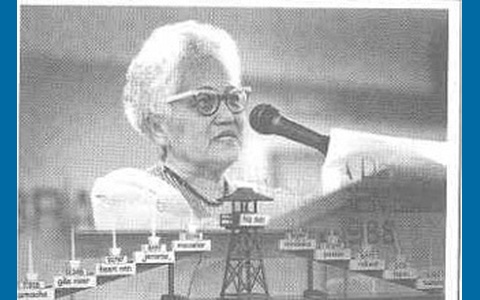

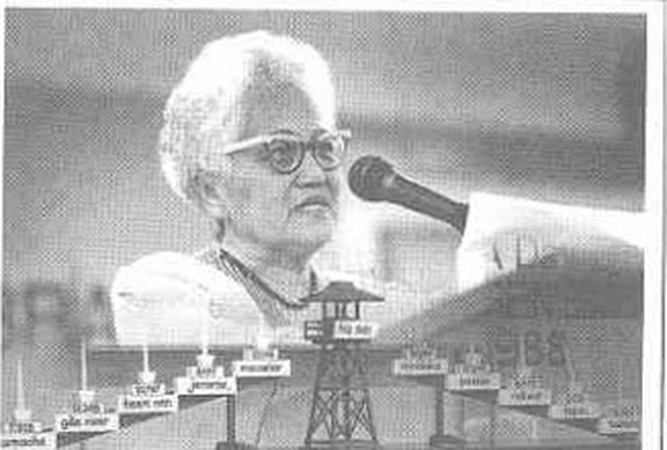

Tsuyako "Sox" Kitashima - Her work

From 1980-1989, Tsuyako Sox Kitashima became heavily invested in the campaign for Redress and Reparations through her membership in NCRR and later, JACL. Thanks to lessons from her father that taught her to become involved in community activity (27), Sox saw the importance of involving herself in this issue. In addition to speaking at Commission hearings, letter folding, addressing, sealing, and stamping, lobbying Congress at the capitol at least three times, and putting on rallies and workshops to outreach to others in the community, Sox continued to work on this issue even after Redress was issued.

That is, even after the monetary compensation of $20,000 for each person was agreed upon, there were many Japanese Americans who were skeptical, afraid, or not knowledgeable about their eligibility to receive reparations. To help remedy this, Sox worked directly with people on their applications, getting to know each person’s story and identifying very closely with their difficult life experiences. Sox also continued to speak, as she is during Day of Remembrance in 1988 in this photo, about the Redress victory, even once appearing on the Fox Network about the importance of such an issue.

As a Japanese American woman involved with this campaign, Sox fit well within the gender dynamic of the kinds of work that women took part in. Her roles did not consist of heading up the Commission that put on hearings, or becoming involved in politics, or taking on a leadership position within any organization. Sox's work might be characterized by some as all the "behind the scenes," unseen work that actually made Redress and Reparations possible. Although she spoke on her experiences both at the hearings and with press sometimes about the campaign, and put in countless hours to make Redress and Reparations a possibility, Sox's work is not widely known, nor is her story widely told.

But her work and her life experiences, and those of women just like her, are indispensable to this movement. The women of the Japanese American community who became involved in this kind of activism and advocacy work must be recognized for their efforts, for without that our communities are not doing proper justice to those who most deserve it.

Source: Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., A Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

--

From 1980-1989, Tsuyako Sox Kitashima became heavily invested in the campaign for Redress and Reparations through her membership in NCRR and later, JACL. Thanks to lessons from her father that taught her to become involved in community activity (27), Sox saw the importance of involving herself in this issue. In addition to speaking at Commission hearings, letter folding, addressing, sealing, and stamping, lobbying Congress at the capitol at least three times, and putting on rallies and workshops to outreach to others in the community, Sox continued to work on this issue even after Redress was issued.

That is, even after the monetary compensation of $20,000 for each person was agreed upon, there were many Japanese Americans who were skeptical, afraid, or not knowledgeable about their eligibility to receive reparations. To help remedy this, Sox worked directly with people on their applications, getting to know each person’s story and identifying very closely with their difficult life experiences. Sox also continued to speak, as she is during Day of Remembrance in 1988 in this photo, about the Redress victory, even once appearing on the Fox Network about the importance of such an issue.

As a Japanese American woman involved with this campaign, Sox fit well within the gender dynamic of the kinds of work that women took part in. Her roles did not consist of heading up the Commission that put on hearings, or becoming involved in politics, or taking on a leadership position within any organization. Sox's work might be characterized by some as all the "behind the scenes," unseen work that actually made Redress and Reparations possible. Although she spoke on her experiences both at the hearings and with press sometimes about the campaign, and put in countless hours to make Redress and Reparations a possibility, Sox's work is not widely known, nor is her story widely told.

But her work and her life experiences, and those of women just like her, are indispensable to this movement. The women of the Japanese American community who became involved in this kind of activism and advocacy work must be recognized for their efforts, for without that our communities are not doing proper justice to those who most deserve it.

Source: Kitashima, Tsuyako Sox and Morimoto, Joy K., A Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Tsuyako "Sox" Kitashima, Introduction

Tsuyako Kitashima, nicknamed “Sox” to make pronunciation of her name easier, was interned with her sister at Topaz during the war. She was very close to her family, especially after her father’s death, and decided to stay with her sister in Topaz while her mother and other siblings were transported to and interned at Tule Lake. In her biography, Sox speaks vividly about the pain, embarrassment, and degradation she felt, especially during her first meal at the mess halls in-camp.

After leaving the camps and attempting to settle back into her normal life, Sox became involved with NCRR, or the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations in 1980 once the campaign for redress had begun. With time her involvement in the campaign increased significantly, as she volunteered extensively and worked with both NCRR and the Japanese American Citizens’ League, or JACL, to put forth various legislative and campaigning efforts to push through Redress. Overcoming different types of opposition, ranging from skeptical JAs to political opponents, Sox worked tirelessly on the campaign. She participated in letter writing, spoke about her personal experiences during the Landmark Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) hearings in 1981, and lobbied Congress numerous times with the NCRR to push for the Redress bill.

In 1988 when President Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, it became clear that the Redress and Reparations campaign had achieved an unprecedented victory for the Japanese American community, and for the greater cause of justice. Sox’s efforts as a woman who persisted in times of hardship, and showed endless dedication to her community and the causes she believed in played a large part in the victory of the campaign. Even long after Redress was completed, Sox continued her mission by venturing on to educate youth and other communities about the injustices JA’s all over the nation suffered, and how the community was able to hold the government directly accountable to their inexcusable violations of civil liberties. Sox’s work in the campaign can be called “behind the scenes,” as many JA women were, but it is without a doubt that kind of seemingly invisible work that made such an accomplishment possible. The times and feats these Japanese American women experienced and achieved must be told and disseminated so that more people will become aware of the extremely key role they played in Redress, despite restrictions of gender or culture in their life contexts.

Source: Kitashima, Tsuyako "Sox" and Morimoto, Joy K., Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

--

Tsuyako Kitashima, nicknamed “Sox” to make pronunciation of her name easier, was interned with her sister at Topaz during the war. She was very close to her family, especially after her father’s death, and decided to stay with her sister in Topaz while her mother and other siblings were transported to and interned at Tule Lake. In her biography, Sox speaks vividly about the pain, embarrassment, and degradation she felt, especially during her first meal at the mess halls in-camp.

After leaving the camps and attempting to settle back into her normal life, Sox became involved with NCRR, or the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations in 1980 once the campaign for redress had begun. With time her involvement in the campaign increased significantly, as she volunteered extensively and worked with both NCRR and the Japanese American Citizens’ League, or JACL, to put forth various legislative and campaigning efforts to push through Redress. Overcoming different types of opposition, ranging from skeptical JAs to political opponents, Sox worked tirelessly on the campaign. She participated in letter writing, spoke about her personal experiences during the Landmark Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) hearings in 1981, and lobbied Congress numerous times with the NCRR to push for the Redress bill.

In 1988 when President Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, it became clear that the Redress and Reparations campaign had achieved an unprecedented victory for the Japanese American community, and for the greater cause of justice. Sox’s efforts as a woman who persisted in times of hardship, and showed endless dedication to her community and the causes she believed in played a large part in the victory of the campaign. Even long after Redress was completed, Sox continued her mission by venturing on to educate youth and other communities about the injustices JA’s all over the nation suffered, and how the community was able to hold the government directly accountable to their inexcusable violations of civil liberties. Sox’s work in the campaign can be called “behind the scenes,” as many JA women were, but it is without a doubt that kind of seemingly invisible work that made such an accomplishment possible. The times and feats these Japanese American women experienced and achieved must be told and disseminated so that more people will become aware of the extremely key role they played in Redress, despite restrictions of gender or culture in their life contexts.

Source: Kitashima, Tsuyako "Sox" and Morimoto, Joy K., Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story. San Mateo: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Japanese American women, Issei through Sansei, are often taught values that identify very closely with their culture; in general, it is best to not question authority and do as you are told. Growing up, young girls are taught by their families to observe certain ascribed gender roles that involved taking care of family and becoming more domesticated. As a result, they are very rarely thrust into a limelight-filled life of activism and politics, and if they do participate in such activities, stay in the background completing all the “behind the scenes” tasks. It is the men, then, that are at the forefront of particular issues and receive much of the credit. For the Redress and Reparations movement, however, in looking at available sources to analyze the contributions Japanese American women have played, it becomes clear that without their hard work, dedication, perseverance, and leadership, the campaign would not have been anywhere near successful. Although it is names like Dale Minami, Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Minoru Yasui that are well-known, the question has to be asked – what about our women? Where is their recognition?

This project ventures on the topic of women’s roles in the Japanese American community, and, in looking at the lives and times of Nisei women Tsuyako “Sox” Kitashima, Aiko Yoshinaga-Herzig, Cherry Kinoshita, and finally Lorraine Bannai, who is a Sansei, seeks to more closely analyze the role of gender in their work, and question why it is that these women have not received more recognition for their accomplishments. Through this analysis, it becomes clear that for these particular women, family and culture were important. For Sox, Aiko, Cherry and Lorraine, although each had very different experiences in how their lives played out, each woman, with strong values and connections to the cultural traditions and ethics taught to them by their families, also were imbued with an internal strength that led them to seek out involvement in social justice issues, in matters that were larger than themselves. The work that they carried out both in their lives and in the Redress and Reparations movement operated most often under men and these women did not take leading roles as officers or spokespeople of the movement, nor were they aware of the gender roles that played out in this campaign.

However, in light of their gender, each woman overcame enormous adversity, both political and personal, to selflessly devote themselves to a community cause that ultimately, although male-dominated, was female-run. Whether they knew it or not, these four women are but a few of the strong, empowered Japanese American women who, while carrying with them with the influences of family-oriented Japanese tradition and culture, were able to contribute to and achieve incredible things for the Japanese American community as a whole. Here are their stories, and hopefully, finally the recognition that is so long overdue.

(Please view original items for full text and explanations, as those are my own.)

The new Nikkei Album!

We’re excited to share our redesigned Nikkei Album. It’s a work-in-progress, so please have patience as we add more features and functionality. It will be an exciting tool for our community to easily share photos, videos, and text! Learn MoreNew Site Design

See exciting new changes to Discover Nikkei. Find out what’s new and what’s coming soon! Learn More

Discover Nikkei Updates

See exciting new changes to Discover Nikkei. Find out what’s new and what’s coming soon!