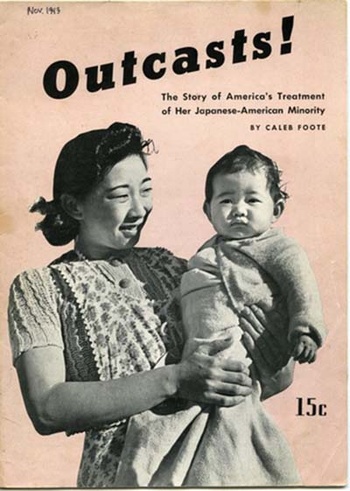

In November 1943—before his release from prison—Foote published his second and most famous pamphlet, Outcasts! In collaboration with photographer Dorothea Lange, who supplied Foote with images for the pamphlet, Foote outlined the conditions leading to the incarceration of Japanese Americans and their current treatment by the government in the camps.

In his forward for Outcasts!, Galen Fisher praised Foote for his work to combat bigotry and defend what he called “The American Way.” He declared that, at a time when paper and resources are precious, the pamphlet was necessary because it “strikes a body blow to keep the Constitution valid for all, and takes square issue with those who would expurgate it for persons of Japanese descent.”

Foote articulated in Outcasts! that the government’s use of “military necessity” to justify the incarceration policy is flawed because it was rooted in racial prejudice. Despite arguments by government officials that threats of sabotage existed and that forced removal was done as a part of “protective custody,” Foote argued that political and economic factors, along with pressure from the West Coast media outlets, were greater causes for the forced removal policy rather than military necessity.

Using detailed evidence and simplistic prose, Foote explained to the reader that Japanese Americans had been loyal long before the war began, that loyalty is never a question of race, and that the forced removal had resulted in grave social and economic consequences for Japanese Americans.

In his concluding remarks, Foote told readers of two potential futures for Japanese Americans: one where gradual resettlement throughout the U.S. and eventually on the West Coast would allow Japanese American families to reestablish themselves. The other, the plan of West Coast white supremacist groups, would try to deprive Japanese Americans of their citizenship despite requiring a constitutional amendment.

Foote told readers that the latter would be a danger to the rights of all Americans, and that Americans needed to take action to protect their rights. Foote left readers with a call to action:

Our liberties and the sincerity of our repudiation of the monstrous doctrine of a master race depends upon your success in removing from our legal system the possibility that under any circumstances any Executive can have the awful power asserted by the President in the order of February 19, 1942, a power intended to be used against the members of one particular race, but nonetheless applicable in stormy years to any unpopular minority. That way lies death to our democracy.

Upon publication, Outcasts! received considerable attention from various civil rights activists. In her own study of race relations during the war, black American academic and activist Edmonia Grant (who I previously wrote about) called Foote’s Outcasts! “[the] best popular presentation of evacuation, relocation and resettlement with attractive photographs. Raises fundamental questions.” Milton Konvitz, a staff attorney for the NAACP, wrote in his letter to the FOR that it was a “very fine statement of the situation of the Japanese Americans,” and famed activist Bayard Rustin (himself a member of the FOR) owned a copy.

Among Japanese Americans, JACL president Saburo Kido praised it as the best pamphlet written on the incarceration. In the JACL’s organ The Pacific Citizen, editor Larry Tajiri opined in his review that it “should be read by every nisei. It is a handbook on evacuation that no American should miss.”

Foote’s pamphlet was not universally accepted though by Christians. In a letter to fellow FOR member John Swomley, Foote lamented that several church stores in California refused to stock his pamphlet because they labelled it as “Jap propaganda.”

In November 1944, Reverend Howard Thurman, the vice chair of the Fellowship of Reconciliation moved to San Francisco to organize the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples. Foote assisted Thurman with various activities, such as organizing teach-ins and workshops on forming interracial coalitions.

At times, Foote clashed with the War Relocation Authority and its head, Dillon Myer, regarding the treatment of Japanese Americans. Foote frequently argued that the WRA did not do enough to defend the rights of Japanese Americans, such as exploiting their labor rather than compensating them fairly for their work. His views at times led him to clash with other activist groups like the Committee for American Principles and Fair Play. In one letter to a friend, Committee Executive Secretary Ruth Kingman stated that while Foote and the FOR were popular, they wanted to avoid being associated with them.

In a May 1945 exchange with Homer Morris of the American Friend Service Committee in response to Dillon Myer’s decision to close the camps by December 31, 1945, Foote argued that the WRA should give incarcerees more time to prepare for the adjustment to life outside the camps. Morris, however, argued that waiting longer would harm incarcerees more, and encouraged Foote to change the language of an article he wrote for Fellowship magazine on the matter.

In June 1945, however, Foote’s situation changed dramatically when he was again sentenced to two years in federal prison for refusing to comply with Selective Service regulations. He then spent the next two years at McNeil Island Federal Prison—the same penitentiary where many Japanese American draft resisters, such as the members of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, were imprisoned. In May 1946, Foote was released early from prison. On December 24, 1947, President Harry Truman pardoned Foote and 1,500 other draft resisters who were selected from a list of roughly 15,000 candidates by Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts.

Foote’s incarceration created a rift within his family, who supported the war effort. Foote later recounted a story from after the war to Cynthia Eller, the author of a study on Conscientious Objectors, that illustrated his father’s disappointment with Foote’s activism:

One day my mother and father were being driven somewhere by a member of the congregation who was a colonel in the Army. And on the way out, the colonel, to make conversation, asked my father, “Well, tell me about your children.” And my father went through his four children. I’m the fifth. He went through his four children. And the colonel had kept track of the numbers. He said “What about the fifth?” And my father didn’t say anything at all.

After leaving prison, Foote attended University of Pennsylvania Law School, where he completed his degree in 1953. His skills as an attorney earned him an opportunity to teach at University of Nebraska Law School immediately after graduating. In 1956, Foote joined the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania Law School. He focused primarily on the rights of prisoners—a passion informed by his own experience in federal prison—and on the injustices of the bail system which primarily targeted the poor.

In 1965, Foote joined the faculty of University of California, Berkeley’s Boalt School of Law. There he taught criminology and later helped establish the school’s jurisprudence and social policy program. He mentored several generations of law students, where he advocated for them to work for the poor and marginalized, until his retirement in 1987.

Caleb Foote died on March 4, 2006 in Santa Rosa, California. His obituary was published in several notable newspapers, including the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. UC Berkeley Boalt School of Law Dean Christopher Edley described Foote as “one of the nation’s preeminent scholars and teachers in both family law and criminal law.” His obituaries included a brief mention of his authorship of Outcasts! during the war.

Among advocates for Japanese Americans, Foote should be remembered as one of the most dedicated to their cause.

© 2025 Jonathan van Harmelen