Among the religious organizations that fought for the rights of Japanese Americans was the Fellowship of Reconciliation. As an interdenominational group that preaches nonviolence and engages in civil disobedience, the Fellowship of Reconciliation has historically been one of the most vocal advocates for defending the civil rights of all Americans. Since its founding in 1916, the group has included noted members like Norman Thomas (who later served as president), Quaker theologian A. J. Muste, Jane Addams, Bayard Rustin, and James Farmer. As Greg Robinson and Peter Eisenstadt previously wrote for Discover Nikkei, activist and minister Howard Thurman led the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s efforts in San Francisco to support Japanese Americans returning to the West Coast.

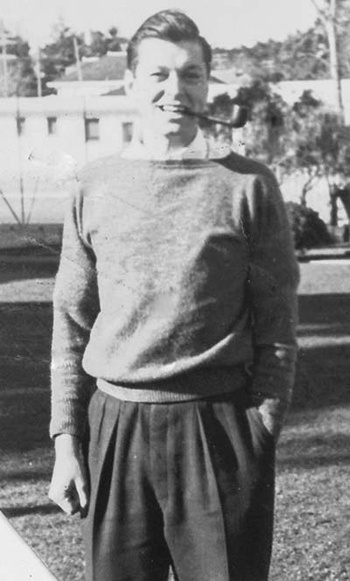

One activist who spent the war years fighting for the rights of Japanese Americans was Caleb Foote. Foote worked tirelessly as a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation to convince Americans that Japanese Americans deserved equal treatment and freedom. Perhaps his most outstanding accomplishment during the war years was his collaboration with photographer Dorothea Lange on the pamphlet Outcasts!

In spite of spending part of the war years languishing in prison as a conscientious objector, Foote achieved a great deal of success in his campaign to support Japanese Americans. Later in life, he continued to advocate for the rights of all as an attorney and law professor at UC Berkeley Law School.

Caleb Foote was born on March 16, 1917, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the son of Reverend Henry Wilder Foote and Eleanore Foote. His father, the nephew of Harvard University President Charles Eliot, was a Unitarian minister who authored several books on the subjects of hymnody and religious freedom in American history. He also served as a trustee to the Hampton Institute, a historically black college in Virginia.

Caleb Foote’s upbringing was defined by Christian principles that emphasized goodwill. According to journalist Larken Bradley, Foote’s mother penned this acrostic for her infant son after his birth:

C-louds of impending war loom darkly o’er our heads (a reference to U.S. entry into WWI)

A-s out of midnight into dawn, thy wailing cry

L-ightens our gloom, from anguish brings release

E-mblem of hope, may thy voice prophesy

B-irth of a better day of righteousness and peaceF-or this thy father’s fathers labored day by day

O-ut of the harsh New England soil to rear a shrine

O-f liberty and law, freedom to worship truth

T-aught by their patient zeal that task shall still be thine

E-ternal as the heritage from age to youth

In 1935, Foote followed in his father’s footsteps and enrolled in Harvard University. He showed his knack for writing when he joined the staff of the school’s newspaper The Harvard Crimson. By 1938, Foote was the managing editor of the Crimson. At Harvard, Foote struck up friendships with his roommate and business manager of the Harvard Lampoon Charles Butcher, Ellsworth Grant, the president of the Crimson, and Caspar Weinberger, who later became Secretary of Defense under President Ronald Reagan—an ironic relationship given Foote’s future pacifism. Grant, who married Marion Hepburn, the sister of actor Katherine Hepburn, on several occasions introduced Foote and his friends to the famed actor on vacations in Connecticut.

Following his graduation from Harvard in 1939, Foote embarked on a road trip across the United States. His travels put him in touch with working class Americans, such as migrant farmworkers in California. His experiences further influenced his decision to embrace pacificism and what some scholars describe as liberation theology. In a June 1941 article for the Boston Globe, Foote declared his intentions to become a conscientious objector in the event of a war.

After completing his master’s in economics at Columbia University in 1941, Foote moved to San Francisco to serve as the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s West Coast Youth Secretary, where he committed himself toward anti-racism activism and establishing new chapters of the FOR in California. On several occasions, he lectured alongside FOR founder AJ Muste at several events in Southern California in October 1941.

In San Francisco, Foote frequently worked with Quaker Josephine Duveneck. During one meeting at the Duveneck house, Foote met Hope Stephens. The two became a couple, and later married in November 1942.

As the anti-Japanese movement ramped up its attacks on Japanese Americans in the wake of Pearl Harbor, Foote went to work on defending Japanese Americans. Early on, Foote and several other members of the FOR hesitated on collaborating with the government on the incarceration to avoid giving the policy their tacit approval. In his own letter to AJ Muste, Foote articulated his own analysis of the “evacuation”—one being a human-made disaster that was driven by greed and prejudice.

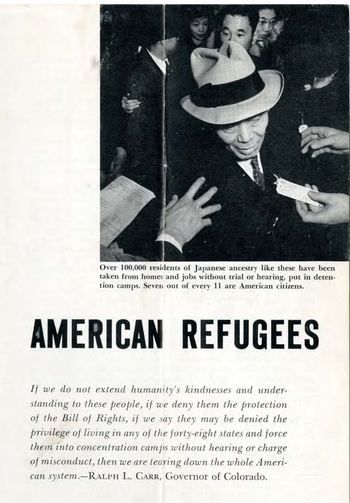

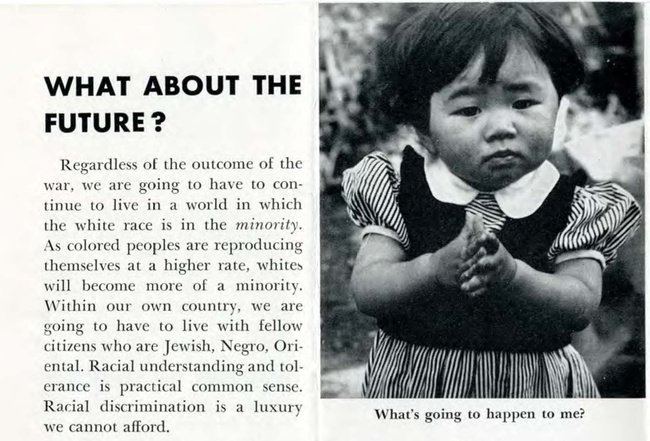

In June 1942, amidst the forced removal of Japanese Americans to Army detention centers, Foote published a pamphlet, “American Refugees,” for the Fellowship of Reconciliation. Putting together quotes from famous government leaders like Secretary of War Henry Stimson and California Attorney General Earl Warren stating that no sabotage had occurred on the West Coast, Foote told readers to lobby the government to change its policy on the incarceration.

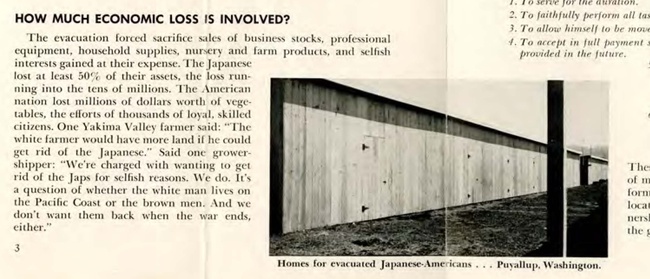

He outlined in his five-point strategy that Executive Order 9066 should be modified to protect civil liberties and that the federal government should compensate Japanese Americans for losses sustained by the initial forced removal. Included in the pamphlet were photos of Japanese American elders and children waiting to be sent to camp taken by Dorothea Lange, along with a snapshot of Puyallup detention center outside of Seattle, Washington.

In a story retold by historian Linda Gordon in her book Impounded, Lange later expressed to Foote her regret over having worked with the War Relocation Authority, stating that she felt implicated in the roundups.

Upon its release, activists with the American Friend Service Committee circulated the pamphlet. When the Army got ahold of the pamphlet and noticed the photographs of Puyallup, Army officials wrote to Joseph Conrad of the AFSC to cease distribution of the pamphlet. Paul Taylor, Dorothea Lange’s husband, recounted the controversy from a different viewpoint.

According to Taylor, the Army called in Lange and Foote for questioning regarding the use of a photo showing an elderly Japanese American man having his tag inspected by a soldier. An Army public relations officer saw this photo as bad publicity for the incarceration and attempted to stop the pamphlet’s distribution. As Taylor recounted, the Army did not take any action because, as it turned out, U.S. Representative John Tolan used the same photo during his committee hearings on the West Coast to investigate the anti-Japanese movement in March 1942.

Several Japanese Americans corresponded with Foote about their life in camp. Activist Kay Yamashita, a close friend of Foote, wrote regularly to him from the Tanforan Assembly Center in 1942. Yamashita provided Foote with detailed depictions of life in camp, and at one point typed in bold letters “THE MENTAL SUFFERING OF THE PEOPLE IS SIMPLY AWFUL.” Yamashita compared the lack of privacy in camp to being like a goldfish in a bowl, and complained of the lack of rights given to inmates in camp. Foote regularly visited with Yamashita and others at Tanforan to check on their well-being.

In another letter to Foote, Yamashita expressed her sincerest thanks for being there: “we appreciate from the bottom of our hearts everything you folks are trying to do and we stand ready to help in whatever way we can… You have shown me, and many others who have read your articles and met you, much and you have certainly given us a new meaning to Life.” Other San Francisco Japanese Americans, like Dave Tatsuno, also corresponded with Foote over the years.

From October 1942 to February 1943, Foote went on a tour of the War Relocation Authority camps to inspect the conditions of the camps. On one occasion, he was joined by Quaker activist Gordon Hirabayashi, who had just challenged the curfew orders. In an interview with Densho, former Heart Mountain incarceree Kara Kondo recounted a story about Foote’s visit to the camp:

I remember Caleb was, we didn't know too much about the Fellowship of Reconciliation. He headed the national organization. He was an imposing figure because our short Japanese stature, and here he was, six foot some, very handsome young man. And Gordon, whose name was well-known among the residents, who had come to a fact-finding, I believe, to see what kind of conditions existed in the camp and the structures within the camp and how the Fellowship of Reconciliation might be able to assist the internees.

On October 27, 1942, Foote travelled to Tule Lake camp to address inmates. A few weeks later, on November 8, he gave a speech at Topaz camp in Utah. On December 19, 1942, Foote penned an article titled “Democracy in Detention” for the FOR’s publication Fellowship, where he described his visit to the Heart Mountain camp and slammed the incarceration as undermining American democracy. The article garnered the attention of many Japanese Americans and was quoted in the Topaz camp newspaper The Topaz Times.

Upon returning from his tour of the camps, Foote lectured throughout Northern California on the folly of the incarceration policy. Speaking before a crowd in San Jose in February 1943, Foote slammed the policy as being based on false rumors and costing American taxpayers $2000 for every Japanese American imprisoned.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Foote’s advocacy work is that he worked with the African American press. In April 1943, black journalist Vincent Tubbs interviewed Foote about his work with Japanese Americans for The Baltimore Afro American. Tubbs, who documented lynchings in the South after World War II and later became the first black American to head a motion picture guild in Hollywood, served as The Afro American’s wartime correspondent in San Francisco. In his interview with Foote, he began by admitting that he knew very little about the wartime treatment of Japanese Americans on the West Coast.

Tubbs split his interview with Foote into two articles. In his April 24th column, he told readers how his interview with Foote changed his perspective on racism in America: “My approach is: the race problem is not the colored man’s concern alone; there are others who can, are and may suffer like injustices and their story should be told.”

Foote explained to Tubbs that his priorities with helping Japanese Americans concerned primarily “the violation of their human rights, without trial or hearing, solely on a racial basis.”

Through his interview with Foote, Tubbs told his readers that the incarceration of Japanese Americans exemplified another attempt by white Americans to steal the property and opportunities of a minority group. Quoting Hearst columnist Henry McLemore, “The white farmer would have more land if he could get rid of the Japanese.”

A week later, in his May 1 column, Tubbs declared to readers told readers that “the evacuation was conducted on a strictly racial basis and therefore must be the concern of all minority groups. Over 100,000 Japanese were evacuated in two months, April 1 to June 1.” He described conditions within the camp leading to the breakup of the family unit. He also argued that the guards of the WRA camps were “illiterate Southerners who harbor inbred racial prejudice.”

In concluding his remarks, Tubbs told readers that there should be a better term than the racial epithet “Jap” when describing Japanese Americans. More to the point, he shared this quote: “Why do you laugh? Change the name and the story is told about you.”

Foote’s activism, however, led him to encounter run-ins with the government. On July 16, 1943, a federal grand jury indicted Foote for refusing induction into the U.S. Army. Foote initially argued that he should not serve in the military on humanist principles, and as a result his local draft board refused to grant him a religious exemption. He likewise viewed the Civilian Public Service—an alternative to military service—as lending legitimacy to the concept of compulsory military service.

When the federal grand jury asked him why he resisted the draft, Foote explained: “Only by my refusal to obey this order can I uphold my belief that evil must be opposed not by violence but by the creation of goodwill throughout the world.” A week later, Foote plead guilty and was sentenced to six months in federal prison for evading the draft. The Los Angeles Times dignified Foote with label of being a “Defiant Conchie.”

© 2025 Jonathan van Harmelen