Midori Kobayashi of Seishu Gijuku University — Friends of Eiichi Shibusawa and Einstein

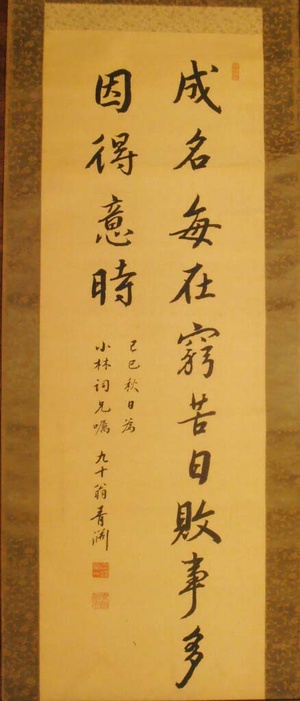

When I heard that “I have a hanging scroll handwritten by Eiichi Shibusawa at home,” I couldn’t believe my ears at first, but when I saw the photo that was sent to me by email, my eyes were opened wide. What’s more, this story was coming from the grandson of a famous figure in the history of Japanese immigration to Brazil.

In a previous column, I wrote that there is a plaque at the Pindorama Hall and the Japanese Model School in Mogi City that reads, “Total friendship, total effort (everyone works together in harmony), written by Eiichi Shibusawa, the 89th Elder.” This time, it is handwritten, making it an even more valuable item.

The person who sent this email was Kobayashi Masato (forty-five years old, third generation), who performed the magnificent sword dance of the Byakkotai when the Seiwa Tomo no Kai recently toured Ancheta Island. Mr. Masato is the grandson of Kobayashi Midori (born in Fukushima Prefecture, 1891-1961), an intellectual, adventurer, religious leader and educator who founded the Seishu Gijuku in São Paulo before the war and published a magazine.

According to “Shibusawa Eiichi in Japan and Kobayashi Midori in Brazil,” written by Masato, “The ‘Shibusawa Eiichi Biographical Materials’ states that ‘June 9th, 9am, Kobayashi Midori visited Asukayama’ in 1929, and met Kobayashi four times after that.” He visited the Asukayama residence with a letter of introduction written by Harada Suke, a close friend of Kobayashi’s and former president of Doshisha University, and appealed for the significance of and support for Seishu Gijuku.

According to the note, Shibusawa sympathized with this appeal, and at a subcommittee meeting of the Committee on Japan-U.S. Relations held at the Tokyo Banker’s Club on July 11, he was recorded as saying, “If we had been prepared from the beginning for the issue of immigration to North America, it probably wouldn’t have turned out the way it has today (Editor’s note: the anti-Japanese movement). As the saying goes, ‘the last car in trouble is a lesson to the last car,’ so I thought that we should take more appropriate measures now regarding the future of the immigration issue in South America, and so I sympathized with the proposal of Kobayashi Midori, president of the Sao Paulo Gijuku in Sao Paulo, Brazil.”

Shibusawa sent letters of introduction to Kobayashi to many influential people, seeking their support for his business. Through these connections, Shibusawa presented Kobayashi with a hanging scroll to commemorate his 90th birthday (1930).

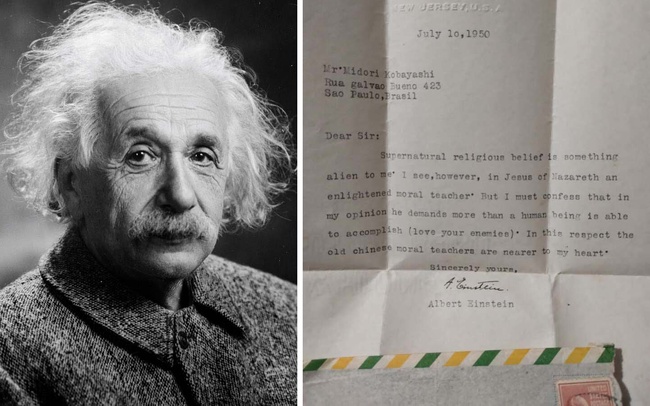

Masato also sent me another photo. It was a letter addressed to his grandfather from Dr. Albert Einstein, who is famous for the theory of relativity. The letter read as follows:

Q: What do you think about God and Jesus Christ?

Dr.: I am not a fan of supernatural religions. But I see in Jesus of Nazareth an enlightened moral teacher. I must confess, however, that in my opinion he demands more than man is capable of carrying out (i.e., loving thy enemies). In this respect the moral teachers of ancient China are closer to my heart.

In other words, they were engaged in a religious debate as early as 1950. Details of how they met are not known. However, the fact that a Japanese immigrant to Brazil had a friendship with the “father of Japanese capitalism” and the “greatest physicist of the 20th century” is noteworthy in itself.

Grand-Scale Japanese Immigration in the Meiji Era

Kobayashi Midori graduated from the Faculty of Theology at Doshisha University in Kyoto and travelled to Hawaii in 1916. He was a Protestant who moved to the US mainland and studied at Auborn Theological Seminary in California. Leaving behind North America, where anti-Japanese sentiment was on the rise, he travelled to Brazil in 1921 and studied Portuguese at Mackenzie University whilst writing articles for the Brazilian Times in São Paulo. After founding the magazine Citizen, he opened a Sunday school to spread Christianity before opening the Seishu Gijuku in 1925. He established a Christian church within the school and was one of the founders of the All-Brazil Judo and Kendo Federation.

I think this is a typical profile of a “large-scale Meiji Japanese immigrant” among early immigrants.

A specific pattern would be someone born on the side of the shogunate or in a pro-shogunate territory, receiving a higher education at a university, heading to Europe or the United States in an attempt to promote global development for the Japanese, but being thwarted by rising anti-Japanese sentiment, eventually moving to Brazil.

These include Hoshina Kenichiro (Ehime Prefecture), who published the first Japanese-language newspaper in South America, Nanbei Shuho, and founded the Alvarez Machado Colony in the early days of immigration; Nishihara Seito (Kochi Prefecture), who served as a member of the House of Representatives and the fourth president of Doshisha University before moving to the United States and relocating to Brazil where he ran a farm; Conde Koma (Iwate Prefecture, Maeda Mitsuyo), who traveled first around North America and then South America before bringing jujitsu to Brazil; and Wako Toshigoro (Nagano Prefecture), an immigrant from the United States who was involved in the founding of the first three Japanese-language newspapers in Brazil and who was instrumental in the founding of Aliança, which celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. These include Onaga Sukenari (Okinawa Prefecture), who traveled through Peru and Bolivia, traveled down the Amazon, and came to Brazil where he was involved in the founding of the Kyuyo Association; Miura Saku (Kochi Prefecture), who went to Brazil as a judo instructor on a Brazilian warship, became the owner of the Japan-Brazil Newspaper, and repeatedly criticized the Japanese government, being deported three times before returning to Japan via Europe; and Kishimoto Koichi (Niigata Prefecture), who studied Russian at the Japan-Russia Association School in Harbin, northern Manchuria, went to Brazil and published the forbidden book Isolated on the Battlefields of South America, which described the persecution of Japanese immigrants during the war, and was sued for deportation by the public security police.

*This article is reprinted from the Brazil Nippo (September 3, 2024).

© 2024 Masayuki Fukasawa