In the first part of this article, we explored the context of Japanese migration to Mexico and the path that led the Nishikawa family to settle in the country. We also saw how early attempts at entrepreneurship in the food industry led to the creation of a key association in the history of the Japanese peanut.

In this second installment, we’ll delve into the registration of the product’s first patent, the evolution of its recipe, and the challenges it faced during its production. We'll also discuss the role of the Nishikawa family in consolidating the business and the events that defined the future of Japanese peanuts in Mexico.

The Masakatu-Nishikawa-Nakagaki association

In 1950, Mr. Tenzo changed his address again, settling in the Colonia Moderna, at Miguel Ángel No. 33. In this environment, he decided to start a business with two other partners: Mr. Hirata and Mr. José Yoshiharu, who, according to some records, was naturalized as a Mexican.

The three partners set out to develop a recipe that used peanuts as the base ingredient for the production of a new and innovative sweet. Their inspiration was okoshi, a traditional Japanese sweet made with puffed rice and other grains bound with caramel or syrup, which in Mexico is called palanqueta.

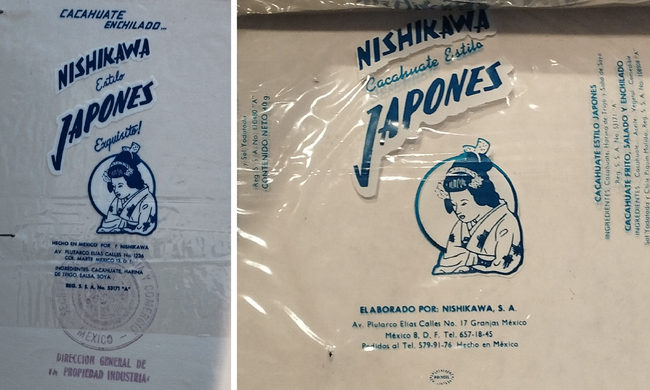

The company was known as Cacahuate Oriental and was registered as Masakatu by the Mexican Institute of Industrial Property. The patent number was 67808, registered on July 7, 1951, and it appeared for the first time with blue oriental-style lettering and the characteristic blue and white geisha profile.Unlike the Japanese sweet okoshi, which uses puffed rice and syrup, the Cacahuate Oriental recipe was based on a mixture of peanuts with honey, salt, or chili.1 The partnership between Mr. Hirata, Mr. Yoshiharu, and Mr. Tenzo aimed to innovate in the Mexican candy market by introducing this new product, which is why they were initially called “Japanese peanuts.” Mr. Alberto commented that the reason for the name was “because they were Japanese and produced peanuts.”2 Later, the name began to vary.

However, when manufacturing and distributing the product began, sales were not as expected, and peanut production failed to generate the expected profit. As a result, the partnership between the three men ended. But Mr. Tenzo's spirit remained strong, and he decided to continue the business on his own, even without the help of his partners; therefore, he continued producing the recipe.

In February 1956, the peanut business continued under the direction of Mr. Tenzo, now registered under patent number 56479. During this new phase, he made a small modification to the recipe, which contributed to the product's commercial success, although still on a smaller scale.

Noticing this growth, Mr. Hirata and Mr. Yoshiharu saw an opportunity to obtain royalties, arguing that the peanut's success had been the result of the three of them working together and that the new recipe belonged to them. However, Mr. Tenzo refused to grant them the royalties they sought, as they had both left the partnership when the business failed to generate the expected profits initially.

Immediately after, in January 1957, Mr. Hirata's company, Masakatu, had passed to his former partner, José Yoshiharu. Subsequently, on July 3, 1957, the General Directorate of Industrial Property sent a notice to Mr. Tenzo. The document informed him of a lawsuit related to the infringement of rights over Mr. Yoshiharu's formula, although it is unknown whether Mr. Hirata was involved. The reason for this was the argument about the similarity of the formula due to “the composition of matter for coating peanuts and the like.”3

The resolution issued on November 4 of the same year established the following:

Mr. Tenzou Nishikawa, through his representative and in accordance with the terms of the document, a copy of which is attached, has requested from this General Directorate the administrative declaration of nullity of patent 56479, which covers a composition for coating peanuts and similar, and which is your property.

The settlement of the lawsuit invalidated Tenzo Nishikawa's patent because it protected a specific method of coating peanuts. However, this did not stop him, as the business could continue operating without making any changes to the way the peanuts were coated. In the following years, new coating methods emerged and new ingredients were introduced into the recipe, allowing the product to evolve and become more differentiated. Furthermore, his new variation on peanuts was made using the recipe of a Japanese friend living in Brazil. 5 Although Nishikawa’s patent was voided, this did not prevent him from continuing his business, as his recipe and coating method had evolved, differentiating themselves from the original.

The Way of the Japanese Peanut: Innovation, Controversy, and Rebirth

The product’s distribution began with the sale of peanuts from Mr. Tenzo’s home, which also served as the factory where not only the peanuts were produced, but also the wrappers. His home and factory were located at Miguel Ángel #33, in the Colonia Moderna neighborhood. Production was minimal, but sales were significant enough to support his needs and those of his family. Therefore, sales were not limited to the factory itself, but distribution was now broader.

1960 was a year of change, a turning point in history. While the world witnessed the rise of new industries and social transformations, in Mexico, the fate of a small but innovative product was about to be defined: the Japanese peanut. Not only would the product change, but so would the lives of the Nishikawa family.

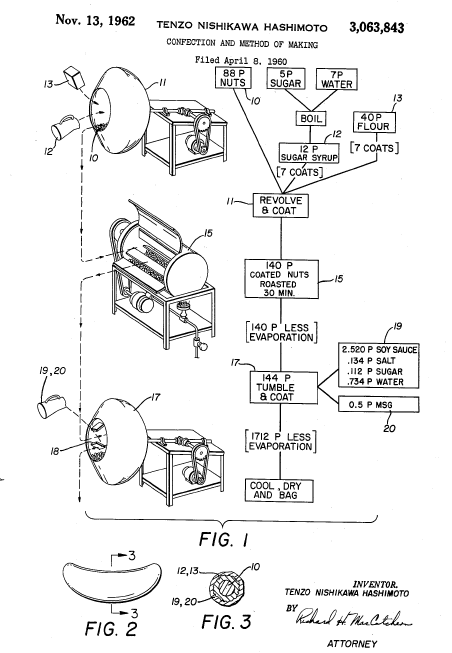

January of the same year marked the marriage of Fusako Nishikawa, the second daughter of the Nishikawa Yonemoto family, to Mr. Jesús Koga, a kibei nisei. This term refers to young men who received a military education in Japan. Jesús Koga, of Japanese descent, was born in Sonora, Mexico, but at the age of six was sent to Fukuoka, Japan, with his brother Jorge. After the normalization of relations between Mexico and Japan in 1952, he returned with his parents to Mexico City (then the Federal District), although he had no knowledge of Spanish.With his business afloat, Mr. Tenzo traveled to the United States, where he registered a patent, number 3063843, in his name, Tenzo Hashimoto Nishikawa. Nishikawa's peanut manufacturing method had key differences from Masakatu's recipe, including modifications to the formula and the development of a specialized production machine.

Furthermore, the Masakatu recipe called for honey, salt, or chili, but the new recipe uses soy sauce, syrup, and flour; these six ingredients were not present in the original recipe. It is also based on the sweet known as araré, which, according to the Cocinista website:

“Arare was first created in Japan during the Edo period (1603–1868), making it a snack with a long history. Initially, it was eaten by samurai as a quick source of energy. Over time, its popularity spread to all social classes in Japan, evolving into a variety of forms and flavors.”7

Thus, the creation of Nishikawa Japanese-style peanuts led to the creation of a product that fused Eastern tradition with the flavor of soy sauce and Mexican peanuts, uniting both cultures in a single bite. With the help of his four children and wife, the business began to emerge under the name Tenzo Nishikawa Japanese Peanuts, also featuring the blue and white geisha's profile image.

With the help of Mr. Tenzo's son-in-law, Mr. Jesús Hideo, he used a bicycle to transport packages of peanuts containing 200-gram bags to the candy stores in La Merced, depositing them at candy stores and shops in the hope that the product would be sold. Once the week was over, he would collect the profit from the peanut sale. Due to the product's widespread acceptance, the profits could not be hidden, and due to Mr. Jesús's poor understanding of Spanish, they attempted to steal the money obtained from the peanut sale on several occasions. After the expiration of its patent in 1967, there are no clear records regarding the fate of the Masakatu company. It is unknown whether it continued operating or ceased commercial activities, but the failure to renew the patent suggests that it lost market presence.

Eventually, Mr. Tenzo had a little income, enough to distribute “to the children […] he told my mother “if you want, I'll leave you the brand and some […] tools to make peanuts, […] [which was only] a huge packaging machine that wasn't pneumatic but was entirely mechanical.” 8 Jesús Koga, in addition to being Tenzo Nishikawa's son-in-law, had already worked with him before the company came under the management of his wife, Fusako Nishikawa.

He was one of Tenzo's trusted men and played a key role in the business's growth. However, the company did not pass to Jesús, but to his wife, Fusako, who inherited the business. Jesús Koga supported her in the expansion and consolidation of the brand, playing a fundamental role in its distribution and supervision. Mr. Alberto, who had already been born at that time, remembers that oil was poured into one of the machines, which was used "to make the bags. We had to make the rest by hand, weigh them one by one on a small scale, and seal them by hand." 9

Over time, the couple wanted to expand their market, and to do so, they needed a larger factory. But economic difficulties complicated their desire to do so, as no one wanted to lend them money, especially not the banks, leaving them with the only option: to go with three private individuals. Mr. Alberto, Mr. Tenzo's grandson, explains that they went with:

“Mrs. Maria, Mrs. Elvira and Mr. Abraham [who] knew my great-uncle because I think he was renting the house from him, so they told him they could borrow money, and my dad and mom showed up. And they went to the Jewish man’s house, he bought them coffee, they drank it and left the cup there, and then, my mom says that Mr. Abraham grabbed the cups and looked at them, then he put the cups down and said to them “well, how much money do you want?”10

The loan that allowed the business to consolidate, according to Mr. Tenzo's grandson, was granted after a curious coffee bean reading. While this anecdote remains in the family memory as a peculiar event, the truth is that the financial support was key to the company's expansion.

By 1970, production had grown so much that the family could no longer manage it alone. With the support of Mr. Jesús, who not only distributed but also began supervising the product, five more workers were added to the manufacturing process. That same year, the factory and the family moved to the Marte neighborhood, at Plutarco Avenue #1236. In 1973, the brand was officially registered with the Mexican Institute of Industrial Property (IMPI) under SSA number 53171, becoming one of the first to formalize the Japanese-style peanut industry in Mexico as a microenterprise.

If the Japanese peanut is a symbol of the fusion between Mexico and Japan, why is only one name remembered in its history? History isn't static, and perhaps it's time to question what we thought we knew.

* * * * *

Notas

- IMPI, Divisional Directorate of Information Systems and Technologies, Section: Inventions and Trademarks, January – December, 1951, p. 2754.

- Interview with Masao Alberto Koga Nishikawa and Makoto Sashida prepared on August 1, 2024, min. 9:20.42.

- IMPI, DDSTI, Section: Inventions and Trademarks, Administrative Notifications and Declarations on Patent Invalidity and Invasion of the Rights Conferred by Patents, July 1957, p. 1036.

- IMPI, DDSTI, Section: Inventions and Trademarks, Administrative Notifications and Declarations on Patent Invalidity and Infringement of the Rights Conferred by Patents, November 1957, p. 1818.

- Consulted on Nishikawa's official website, in “ The untold story ”.

- US Patent and trademark office, Confection and method of making , No. 3063843, Tenzo Nishikawa Hashimoto, November 13, 1962.

- Vine . In Cocinista encyclopedia, Arare .

- Interview with Masao Alberto Koga Nishikawa and Makoto Adriana Salvador Sashida prepared on August 1, 2024, min. 13:14.66.

- Interview with Masao Alberto Koga Nishikawa and Makoto Adriana Salvador Sashida prepared on August 1, 2024, min. 14:36.15.

- Interview with Masao Alberto Koga Nishikawa and Makoto Adriana Salvador Sashida prepared on August 1, 2024, min. 15:54.60.

Photos courtesy of the Nishikawa family.

© 2025 Ana Karina Martínez Lorenzo