Nikkei history is not well-known in Japan today, says Kanae Aoki, curator of the Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama (MOMAW). But the MOMAW has embarked on a project to change that, bringing Japanese diaspora history back to Japan through a collaboration with the Japanese American National Museum (JANM).

It all began with the second Wakayama homecoming festival, held in 2023. Modeled off Okinawa’s Worldwide Uchinanchu Festival, the Wakayama Kenjinkai World Conference invited the descendants of emigrants from Wakayama prefecture back to Wakayama for a host of cultural events and celebrations. To contribute to the festivities, the MOMAW decided to put together an exhibition highlighting works by artists born in Wakayama who were active in the United States. Over the years, artworks by Wakayama emigrants had already been brought back to Japan and made their way into the MOMAW’s collections, but these were mainly from the East Coast art scene.

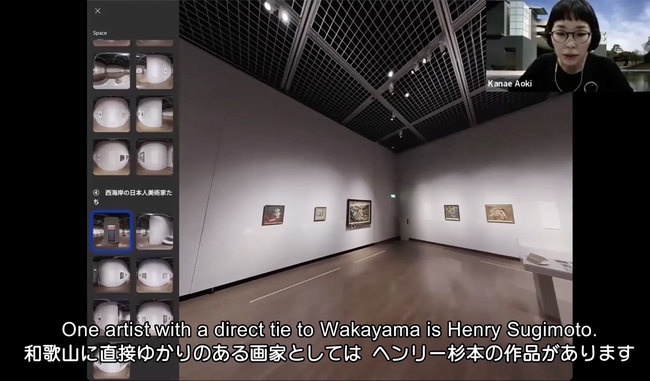

To expand the scope of the show in relation to immigration history, MOMAW wanted to highlight artworks from the West Coast, the destination of the majority of Japanese immigrants to the US. MOMAW reached out to JANM about including works of art and other items from JANM’s permanent collection. With the world’s largest collection of Japanese American art and artifacts, JANM holds a number of paintings and other works by notable Wakayama emigrant artists, including Henry Sugimoto and Tokio Ueyama, and Toyo Miyatake. With JANM’s participation, the exhibition showed an expansive collection of art related to Wakayama emigrants active all over the United States (and is still viewable as a virtual exhibition). The project touched off an ongoing collaboration between JANM and MOMAW. Since then, the two museums have worked together to research and bring to light the interconnected histories of Wakayama prefecture and its emigrants to California and beyond.

From Wakayama to California

The history of Wakayama-to-California migration traces back to the Meiji period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Japan opened to the outside world. Like so many other migrants throughout history, many emigrants left Wakayama in search of economic opportunities. Those who went to California often managed to find jobs that applied skills from back home, especially in the fishing industry. Fishing played (and still plays) a key role in Wakayama’s economy, and many emigrants found work in California’s fisheries. They were especially active on Southern California’s Terminal Island, which became known for its Japanese American fishing community, and in Northern California’s fishing hotspot, Monterey.

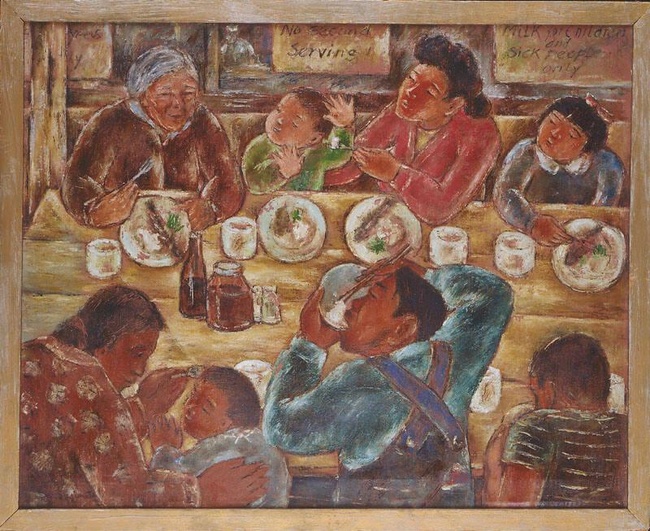

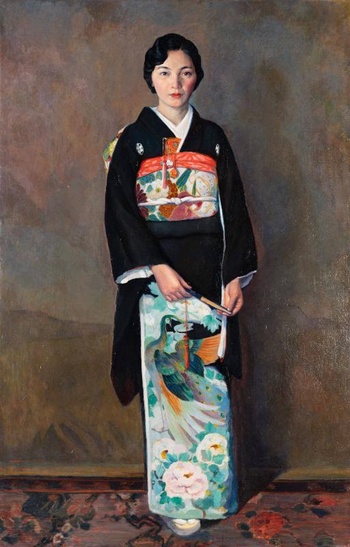

Of course, not all of Wakayama’s emigrants were fishermen and in fact, many immigrants contributed to other industries, such as the flower industry and gardening. Yet art also played a role in Japanese immigrant communities at that time, as MOMAW’s exhibition attests. Perhaps the best-known Wakayama artist on the US West Coast was Henry Sugimoto. Born in Wakayama city, he created numerous works in the concentration camps during WWII. He later became a leader in Japanese American rights during the 1970s and ’80s. Other Wakayama artists active in the twentieth century US included Tokio Ueyama (founder of Little Tokyo gift shop Bunkado), and he played a central role in the Los Angeles art scene, by bringing several other important artists such as Toyo Miyatake and Boshicho Okamura into a Japanese artists’ group known as Shaku-do-sha.

Though the Transbordering exhibition included a wide range of artworks, Aoki points out one painting in particular as emblematic of the relationship between Wakayama and California. Henry Sugimoto’s 1937 painting, Seashore of Carmel Highlands, shows the rocky coastal seascape of Carmel, California, under blue-brown cloudy skies. “This reminds me of the coastline of Southern Wakayama,” Aoki observes, “very similar.” As Sugimoto was from Northern Wakayama, “This could be my own interpretation,” Aoki adds. Still, even as Sugimoto was painting California, perhaps he was also painting the sights of his homeland, as well. In some ways, perhaps California and Wakayama were not so different.

A Transpacific Partnership

Though the MOMAW’s Transbordering exhibition has now closed, the partnership between JANM and MOMAW continues. The museums hosted collaborative symposia in 2022 and 2023 to bring together scholars and cultural professionals to explore the Wakayama-California connection. And in May 2024, JANM and MOMAW became sister museums, cementing their collaboration and laying the groundwork for continued research on Wakayama-US connections.

The collaboration isn’t limited to research or museum exhibitions. Education is integral to the mission of both museums, and as Aoki explains, this collaboration has proven quite educational for residents of Wakayama. Though Wakayama prefecture is Japan’s sixth-largest imin-ken, or “emigration prefecture,” many of the region’s residents do not know much about the experience of emigrants, she says.

Through the museum partnership, however, several schoolteachers from Wakayama have had the chance to visit JANM in person and learn about Japanese American history firsthand. Through this experience, says Aoki, “The teachers learn directly about Japanese American history as part of our local history. Once they learn, with their own eyes, they can teach this to the pupils—not just the information, but their own experience.” After visiting JANM, one sixth-grade teacher even included Wakayama emigrants like Henry Sugimoto in a class play about Wakayama history.

Students in Wakayama have also attended JANM’s virtual visits. According to Aoki, many Japanese students were surprised to discover that JANM’s museum educators not only looked like them, but also knew so much about the history of Wakayama. “That was an eye-opening experience for students,” Aoki says. Through these efforts to connect Japanese American history to Wakayama’s own history, Japanese students “can see the world through their own regional history.” By keeping the focus on emigrants from Wakayama, these educational programs make Japanese history less insular and more connected to the wider world, without losing a personal connection.

Transbordering Symposium

This January 18, JANM hosted the third collaborative symposium, “Transbordering: From Wakayama to California.” The symposium brought together scholars of Wakayama and Japanese Californian art and history to explore the many ways these histories intersect and connect, and to share “how scholars, art historians, and museum professionals on both sides of the Pacific are trying to understand the Japanese experience.”

The first panel, featuring Aoki, JANM’s Curator and Director of Collections Management and Access Kristen Hayashi, and the MOMAW’s Educator in Chief and Curator Ichiro Okumura, focused on both museums’ work connecting art and migration history. Hayashi gave a virtual tour of some of JANM’s many works by Wakayama-born artists. She even shared a photograph of the Mio Cafe on Terminal Island, California, a small business operated by a family that also operated a bakery in Wakayama. Okumura expanded on the artworks of Wakayama emigrants by diving into MOMAW’s collection. He noted that most artists went to the US as migrant workers, not as artists—yet their thriving art careers in the US attest to their dedication to self-expression and creativity. Then Aoki spoke about the ongoing collaboration between JANM and MOMAW. The panel offered a comprehensive look into the art and experiences of Wakayama’s emigrant artists.

The second panel turned the focus to resources and research on emigration history taking place in Wakayama itself, with four speakers from the prefecture’s cultural institutions. Professor Etsuko Higashi of Wakayama University explained the university’s expansive materials related to Wakayama migration, from public exhibitions to recent acquisitions. From Haruna Higuchi of the Wakayama Civic Library, attendees learned about the library’s extensive emigration archive, open to both researchers and the general public. Natsuko Yamashita of the Wakayama City Museum shared the museum’s collection of works by Henry Sugimoto—personally donated by Sugimoto himself—including handcrafts created in the World War II concentration camps. Finally, Hayato Sakurai spoke about emigration-related materials held at the Taiji Historical Archives in Taiji, a town in Wakayama prefecture, including artifacts and documents from Taiji emigrants in Terminal Island. The panel revealed that Wakayama holds a wealth of archival materials and artifacts related to its emigrants, which will surely facilitate more enlightening research on the region’s rich transpacific connections.

The third panel turned the focus to the Nikkei experience in the United States, with JANM Curator Emily Anderson speaking about her research on street preachers in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, shedding light on the dynamic daily lives of these Issei Christians. Then, UC Berkeley Professor Andrew Leong introduced the novels of Shōson Nagahara, revealing a much darker side of the Issei experience in Los Angeles. Although Shōson had connections to the well-known, well-off artists of Japanese Los Angeles, his novels painted a strong contrast between the lifestyle of the likes of Tokio Ueyama and that of Issei barely scraping by in the same city. The two contrasting visions of Issei life in twentieth-century Los Angeles offered by Anderson and Leong pointed to the complexity of Japanese immigrant experiences in the US writ large.

Taken together, the panels offered a fascinating look into both the experiences of Wakayama emigrants in the United States, and the many opportunities to continue to expand our knowledge of their stories. In the coming years, the transborder partnership between JANM and MOMAW is sure to shed more light on the collective histories, personal stories, and artistic visions that have made the transpacific Wakayama-California connection so rich for over a century.

© 2025 Marjorie Hunt