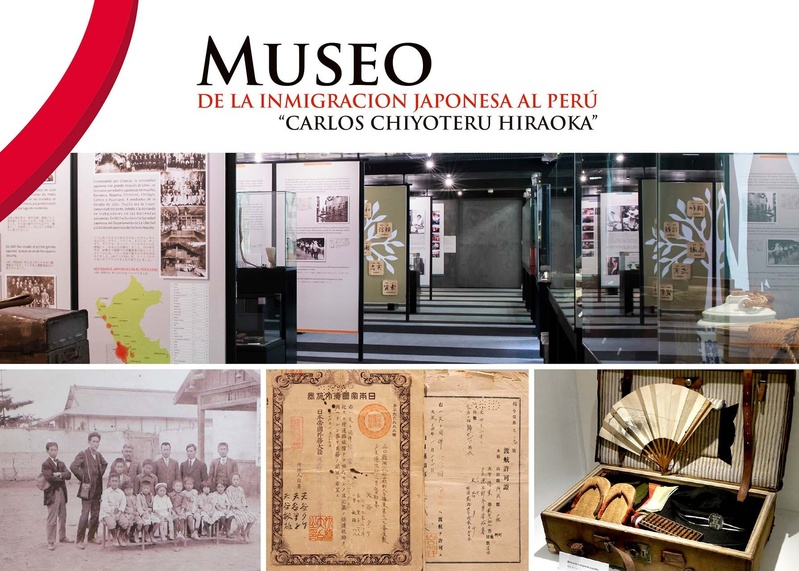

The Carlos Chiyoteru Hiraoka Museum of Japanese Immigration to Peru is being modernized.

With technology as its main ally, this facility—which exhibits objects and documents alluding to the Nikkei community and tells its history through panels—pursues three major objectives.

One of them is to digitize the history of Japanese immigration to Peru, a mammoth and long-term task that involves, above all, transferring tens of thousands of photographs to virtual format.

Another aspect: the reorganization and classification of the pieces it houses. Previously, they were stored in a warehouse, unprepared. Now, they are divided into two spaces, each conditioned according to the characteristics of the heritage stored. The objects, depending on their nature, require different temperatures or contexts for their safe preservation.

The third: reaching out to the public more easily by facilitating their immersion in the museum through technological tools such as QR codes or audio guides; as well as offering tours tailored to the profile of group visitors, since guiding 3- or 4-year-olds in kindergarten is not the same as guiding young history students.

Director Hiromi Maegushiku focuses on tailoring museum tours to the tastes and interests of the visitor group to make them more appealing.

For example, a group of university fashion design students recently visited the museum and were interested in the uchikake. Perhaps the history of immigration held little interest for them, but their eyes were drawn to the kimonos.

If a group of kindergarteners goes to the museum, what can you offer them to keep them from getting bored? Building origami boats to teach them that immigrants to Peru arrived by sea is a fun way to introduce them to history.

Treasures to be digitalized

Many of the images the museum is digitizing come from the archives of Japanese photographer Kiyoshi Sato, a prominent community documentarian thanks to the photos he took over six decades at weddings, institutional anniversaries, New Year’s gatherings, and openings—in short, any social or family event organized by Japanese people and their descendants.

Coordinator Jessica Moromisato explains that the goal of digitizing them is to share them with the public without them having to manipulate the originals to prevent their deterioration or mistreatment.

There’s still much work to be done. Kiyoshi Sato’s archive alone is estimated to contain some 40,000 negatives.

The work isn’t limited to digitizing the images. The museum team also has to trace their origins, date them, and classify them.

Another front-line task is converting the community’s print media throughout its history into virtual format. Substantial progress has already been made here: thanks to an agreement between the museum and the Hoover Institute at Stanford University, more than 1,500 pages of Japanese newspapers circulated between 1912 and 1941 have been digitized.

Leaving the stone age behind

2024 was a special year for the Peruvian Nikkei community, as it celebrated the 125th anniversary of the arrival of the first Issei to Peru.

At this juncture, the museum’s importance as a repository and transmitter of the history of the Japanese people and their descendants grew.

Aware of the challenge this entails, Hiromi Maegushiku took over as director of the museum last October. She is supported by her experience as coordinator of the “Carlos Chiyoteru Hiraoka” program for approximately six years.

The Nisei, whose parents are Okinawan, recalls that during her previous career, she worked alone; she had to do everything (administrative tasks, organizing objects and documents, attending to visitors, giving guided tours, etc.).

Hiromi, for example, would gather photo by photo and categorize them into categories like “schools” or “sports.” With her hands, and at a glance.

That’s a thing of the past. Museum work has become more professional, and today six people work there, aided by technology.

The director emphasizes the contrast between the past and the present. “It was practically like being in the Stone Age,” she comments, referring to her years of manual collections management. Now, however, “a giant step has been taken toward the proper functioning of the museum.”

“We’re reaching 125 years of immigration, and we’re improving in terms of conservation and preservation,” he says.

The koto of nightmares

Hiromi Maegushiku temporarily stepped back from the museum in 2022. However, she remained informally involved with the institution, lending a helping hand when requested, until she formally returned to serve as its director.

“I accepted because I’m very attached to the museum; you can’t just leave it hanging,” he says.

Her extensive experience as a coordinator allowed her to thoroughly understand all the pieces housed in the facility, “such rich material” that she felt sorry it was kept away from the public eye.

“I’m against keeping things hidden,” she emphasizes. Precautions must be taken to maintain their integrity, of course, but it’s about showing them, not hiding them. “You don’t have to keep things, you have to share them,” she insists.

Ultimately, the pieces in the custody of Carlos Chiyoteru Hiraoka, donated by Nikkei families, are part of the common heritage. “They’re well cared for here, and people come to look at them with affection,” says the director.

It speaks of affection because many Japanese descendants who visit the museum and observe the plow, suitcase, trunk, koto, baseball gloves, or passports on display—objects that were once used by or belonged to immigrants—remember their own ancestors through them.

Incidentally, among the things donated by Nikkei people, some stand out for their uniqueness. Coordinator Jessica Moromisato recalls that they once found hair and dirt wrapped in papers in a butsudan; they concluded that the former belonged to the deceased, and that the latter had been removed from the burial site.

Donating objects isn’t always motivated by a desire to share or an act of generous generosity. Fear of the otherworldly can also be a factor. The director recalls a Nikkei family whose maid suffered frequent nightmares in the room they had assigned to her.

Finding no plausible explanation for the phenomenon, the family concluded that the koto kept under the bed was the source of their dream disturbances and decided to get rid of the instrument by giving it to the museum.

Diving into history

The museum is an invaluable space for young (and not so young) Nikkei to learn about the history of their community. Many take the existing infrastructure for granted. For example, the La Unión Stadium Association (AELU).

The director recalls that once the land on which the club would be built was purchased, a large number of Issei and their children collaborated in clearing and leveling it, including her family.

She cites the case of the AELU to show how much it cost to build it, and to let the new generations, who already knew it was built, know that it was not easy at all, that there was a huge combination of efforts behind it.

Visiting the museum will educate you on how the club was built, as well as other major projects (the Japanese-Peruvian Cultural Center, the schools, etc.).

It also serves to reconnect many Japanese descendants with their ancestors, of whom they have lost all reference (even their last name). Hoping to learn about their immigrant ancestor, with no other source to consult, they come to the museum in search of information about their mysterious relative.

The director recalls a family who visited them because their young daughter had dreamed that her now-deceased Japanese grandparents were calling her and wanted to meet their unknown ancestors.

Jessica Moromisato sheds light on the case of a third-generation woman whose father, before dying and hospitalized, tasked her with finding out the story of her grandfather Issei and his koseki. The woman went to the museum as part of her research and even traveled to Okinawa to fulfill her mission.

Even Nikkei connected to the community can delve into their family history through the Pioneers digital database, which stores the names of Japanese immigrants, their arrival dates, and their prefecture of origin.

Visiting the museum has also allowed several members of the community to discover themselves in the photographs on display, a surprise filled with joy and excitement. “That’s me!” they say.

An obaachan, for example, found an image of herself, along with her father-in-law, dressed as a bride when she married by proxy in Japan, before migrating to Peru.

Happiness also comes from discovering a relative, as happened to a boy at La Unión School when he found his father among the photographs in an exhibition of outstanding Nikkei athletes. “‘My dad,’ he said, and he almost cried,” the principal recalls.

The romantic Issei

On a personal level, working at the museum carries a powerful emotional charge for its director. The history it contains and disseminates is the story of her immigrant parents and uncles. She even found photos of her family in Sato’s archive by chance.

Hiromi, the youngest of her siblings, was the recipient of the stories her Japanese mother told her about her arrival in Peru, her first impressions of the country, and her gradual acclimatization to it.

Those stories she heard as a child found extension and reflection in those she discovered in the museum.

Here we can narrate the origin of the relationship between his parents:

“My mom told me that her father came to Peru, and it seems he already knew my father because they were from the same village. My grandfather wanted his daughters to come here to marry two men. My mom came all excited to accompany her father, but then she realized it was so she could get married. Then my mom got upset. She says she said to her father, ‘Why are you bringing me?’ He was outraged. My grandfather told her, ‘I already gave my word; you’re going to make me look bad.’ He got mad at my mom, so since she loved him so much, he said, ‘Okay, I’ll think about it.’”

The story, fortunately, had a happy ending.

“Thank God, my dad was a romantic. It was unusual for an Issei, but my dad was fond of carrying little flowers, a rose, a piece of candy. It seems that my mom fell in love with that, and they got married.”

What’s coming

In January 2025, Lima hosted an international symposium of Nikkei museums from various countries, including Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay.

During the event, museum representatives exchanged experiences and knowledge, and from this interaction they hope to learn from or emulate things their peers can do to improve.

Speaking of progress, Carlos Chiyoteru Hiraoka aims to develop audio guides in Spanish, English, and Japanese, and expand the use of QR codes, which are now available next to the pieces on display and lead to video testimonials from Nikkei artists who describe their fondness for them.

One of the visitors’ favorite objects is a bellows camera that Kiyoshi Sato used to leave behind a wealth of images that portray a community that values its history.

© 2025 Enrique Higa Sakuda