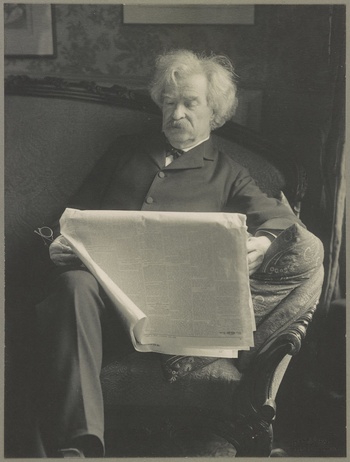

As an enterprising editor of Harvard Illustrated, England sent a copy of the November 1901 edition of the magazine to Samuel Clemens, well known as “Mark Twain,” then living in Riverdale, New York. The edition included a story by Ohashi, “Nature’s Inspiration,” which drew the attention of Clemens. Clemens replied on December 1, 1901, “Dear sir: I thank you very much for that pretty and quaint and charmingly, unconsciously, comical Japanese idyl. It is the coming race ― the Japs. Very truly yours, Samuel Clemens.”1 The text was preceded by an editor’s note, “We cannot refrain from allowing our readers to share our enjoyment of this inimitable bit of English by a Japanese student.” Much of the text is standard for the times in terms of diction and style, but three passages, that follow, are different. They can be taken as pristine writing by student Ohashi:

The young lady in sentimental tone, “Jack! What an inspiring scenery this is! The earth never before appeared to me so beautiful and joyous a place. Beauty and joy saturate on every inch on the earth. These verdant meadows, gray mountains, brown fields, purple forests, blue lakes, and sylvan villages emblazed in the crimson hues of the sun behind the western peaks, haply utter in one hue and cry, Love and Joy.

Twinkling stars, white clouds, drooping mists, sleeping mountains, and dancing forests seemed all restful in Love and Joy. Was not she dreaming her happy love? She never looked so blithe.2

There is no need to belittle the writer, who, after all, had a different background from his fellow students. The story may have been edited only in part, as most of it is in technically correct English. It is worth mentioning that in the third passage, in the dialogue of Jack and Lucy, Lucy says, with no other suggestion in the story of any connection to Japan:

Fresh daisies, happy you look! You tall and graceful goldenrods! I heard the Japanese call you “Geisha-girls.” You pure, everlastings and royal clovers, I envy your joy! You truthful and honest carrots, your smiling lips I kiss!

England must have been as enthused as anyone could be—and Ohashi certainly was—so when Ohashi was told what Clemens had written, the aspiring poet, still in Cambridge, wrote to “Mr. Clemmens” three times, sending him poems on January 7, January 10, and February 14, 1902. The three poems were “Maude and O-Hana,” about an American girl and a Japanese girl, “The Misty Mountain Moon,” and “Music.” This is second poem, which was of interest to Clemens:

The Misty Mountain Moon

Around the slant brows of the misty peak,

Toward the rustic arbor on the rocky ledge

Adele and Jack, with Jet, a spaniel black

Athwrt the green, along the maple hedge,

Strolled both, arm in arm, like lovers young

Into the hovering deepmost mountain mist.

The crescent moon was casting its dim light

Upon the sleeping valleys, calm and whilst

And mildly shed its misty rays on high.

No twinkling stars burned in the clouded sky,

But some faint light shone in the sylvan vale,

With here and there a mirror facéd lake.

They sat there leaning on the arbor rail;

It was his farewell night. ―Tomorrow dawn

His duty, for sweet peace and for the sake

Of concord, to the war would find him gone.The slight sounds of a tender whispering

Were heard, anon the silence, vast and deep,

And then came kisses warm and passionate,

Whilst Jet barked madly at the rocky steep.

The latter poem, as it was published in 1901:

Music

“Music is the quintessence of life and events.”—

Schopenhauer.I listened — first a whispering melody

In which our souls and sense delightfully

Drift on; — a brooklet over pebbly stones; —

A cataract with thunderous roars and moans; —

Then smiles of lovers when they kiss and meet; —

Anon the clash of war; — anon the sweet,

Blithe songs of nightingales; the sudden leap

Of swift fair horses on the hillside steep; —

Now snow or rain; — then as in church we hear

The pealing organ chanting music clear.

The essence of events and life combined,

In thee alone O Music, Joy we find.—Hyde O’Haslie [sic]3

Clemens apparently liked the poems to the extent that he wrote to William Dean Howells, the novelist and literary critic, on January 12:

Say—Howells, don’t you want to discover a Japanese poet & introduce him to the public? It seems to me that his lines about the moon are poetry; also that the satire in the closing lines of the first paragraph exhibits a smart & calculated reserve not found every day in a beginner. …

I cannot claim to know poetry when I see it, but instinct moves me to think that the talent must be in this Jap, else how could he project even the semblance of it into an alien tongue but partially mastered?4

At least one poem was published elsewhere than Harvard, in the Philadelphia Times newspaper. That Ohashi published a few poems is of some interest to literary scholars, in that he may have been the first Japanese person to publish poetry in English outside of Japan (and perhaps in it as well)—an attribute otherwise associated with the controversial poet and ultranationalist Yone Noguchi (野口米次郎), also born in Tsushima (b. 1875).6

Judging from Ohashi’s letter to Clemens and general circumstances, it is likely that Ohashi received some help in composing his poems. On February 14, 1902, Ohashi wrote to Clemens, “I expected to receive from you not such praise as to which my work is not fit but your criticism on my unpolished lines or mistakes, or my other poor points! – because I am a bit of a yellow-beaked bird whose caroling needs a more instruction from the mother bird.” This suggests that Clemens did write back.

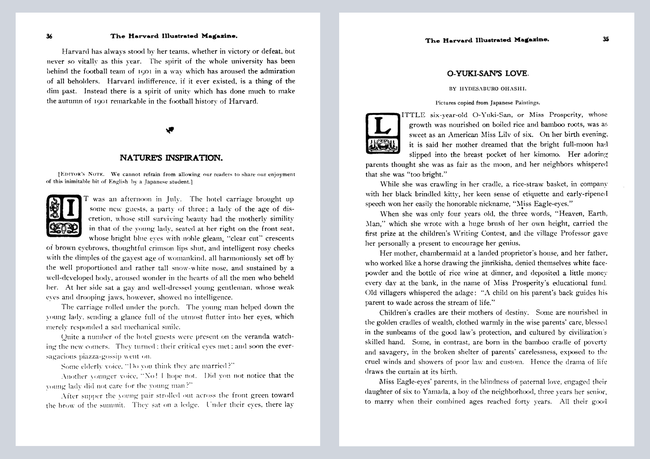

It was a busy time for the aspiring writer. His essay “Nature’s Inspiration” was published in the Harvard Illustrated Magazine.7 A two-page story, “Benjamin Franklin Still Lives,” was published in the same magazine in February 1902.8 Later in the year, in November, another composition, “O-Yuki-San’s Love,” was published.9 The former mentions a “fantastic Japanese lantern” decorating a drawing room, but has no other Japan-related content. The longer love story was quite different. It was certainly edited by England (at least in part), but loaded with Japanese references—enough for a dozen similar romanticized works of fiction about Japan. There was more than enough to make England’s head swim. The story was true to a familiar meme of the times, ending with the suicide of a Japanese woman, such as had shocked New York audiences in the recent past with the hit stage production of Madame Butterfly. The references indicate that they were written by Ohashi, confirmed by mention of the Kiso River (木曽川) which flows through Aichi Prefecture, which would not have been known to England. From the no less than several dozen references, here are a few examples: “boiled rice and bamboo roots” (“shoots” would be correct), “kimomo jinrikisha” (typographic error?), “white face-powder rice wine,” “Yamada and Konoe” (family names), [a summer night’s] “Bon dance.”

In the same year, 1902, Ohashi was accepted as a member of the Pi Eta Society, a Harvard club similar to the Hasty Pudding, which specialized in comic opera. Student dramas were a tradition at the school. Hasty Pudding performances began in 1844; Pi Eta was established 22 years later.

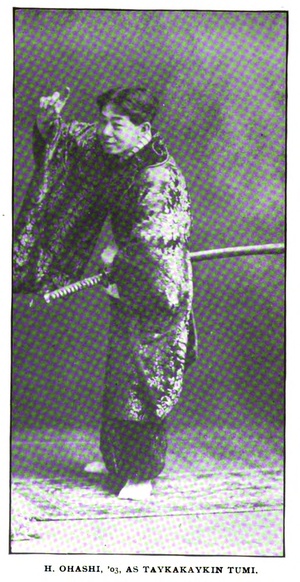

When Ohashi took the stage, it was at the organization’s own playhouse, seating nearly 500. In April, when the club put on a performance of Queen Philippine, Ohashi was cast as Taykakaykin Tumi, Secretary Plenipotentiary to King Philippine of Tavolara. Although the Philippines had been an object of American attention after the islands had been acquired, as a result of the recent Spanish-American War, other than a Filipino war dance in the play, there was no connection between world events and stage happenings. It was just a matter of fun, a two-act comedy with a plot based on a superstition in India regarding an idol’s ear. As was conventional in musical comedies at the time, the twenty-three musical numbers included a love song performed by Ohashi and a coon song with no connection to the plot.10 But in the play, Ohashi, “a Japanese of noble blood and a Pi Eta man,” stood out, performing a “Japanese sword dance, known only to members of noble Japanese families.”11 The published photograph of him doing the dance shows him attired in what appears to be a three-quarters length kimono with floppy sleeves and holding what looks like a typical Japanese sword in a scabbard.12

In one item England wrote about his friend, Ohashi is presented as an internationalist, pacifist and dedicated to justice and truth. He is described a reader of English and German philosophers, suspicious of “tyranny” regarding Emperor Meiji’s rule, rejecting superstition masquerading as religion, and annoyed by the “clumsiness of Japanese character writing.” The latter trait made Ohashi suggest that Japan should adopt the English alphabet and diphthongs. Startling and suspicious, however, is England’s contention that Ohashi had attempted to start a republic, and this had led to “a flying visit” to America. Threats Ohashi received for advocating Japan’s adoption of the Roman alphabet led to his undertaking, according to England.

England asserted that his friend had considered money primarily as a means enabling him to perfect his philosophy of “Positive Knowledge” (a form of positivism?). In England’s obituary of his friend, published in the “Fourth Report of the Class of 1903,” England wrote that Ohashi planned to establish a colony based on “Ohashian Positive Knowledge.” Such observations make sense in light of later efforts by Ohashi. England may have been a major influence, judging from his later socialist views; this political orientation was evident in England’s later writings, such as his futuristic novel The Air Trust (1915).

Notes

- Gary Scharnhorst, “A Sheaf of Recovered Mark Twain’s Letters.” American Liteary Realism 52, no. 1 (Fall 2019): 90, after “Japanese Poet of Harvard Wins Mark Twain’s Praise,” Boston Post, March 23, 1901, 36-39. Scharnorst also mentions in a note an article, “Japanese Poet of Harvard Wins Mark Twain’s Praise” in the Boston Post, March 23, 1902, 20 (not reviewed for the present study).

- Hydesaburo Ohashi, “Nature’s Inspiration,” Harvard Illustrated Magazine 3, no. 2 (November 1901): 36-38. The last page credit line shows “Hidesaburo.”

- Harvard Advocate 72 (October 17, 1901): 122. The family name as printed may have been a pseudonym, typographically incorrect, or both. Coincidentally, the head of the Board of Editors, Joseph Clark Grew, entered the diplomatic service and served as ambassador to Japan in 1932–1941.

- 1902 entry in Mark Twain Day by Day, beta version, at Center for Mark Twain Studies, 3:0672.

- Scharnhorst, “Sheaf of Letters," after Henry Nash Smith and William Gibson, Mark Twain-Howells Letters (Cambridge: Belnap, 1960), 739.

- Noguchi arrived in America years after Ohashi.

- Ohashi, “Nature’s Inspiration,” Harvard Illustrated Magazine 3, no. 1 (October, 1901): 36-39.

- Ohashi, “Benjamin Franklin Still Lives,” Harvard Illustrated Magazine 3, no. 5 (February 1902): 137-38.

- Ohashi, “O-Yuki-San’s Love,” Harvard Illustrated Magazine 4, no. 1 (1902): 35.

- Coon song was the name of popular songs stereotyping Black people.

- L. Guernsey Price, “American Undergraduate Dramatics,” The Bookman 18, no. 4 (December 1903): 374. The photograph appears in Harvard Illustrated Magazine 3, no. 7 (April 1902): 172.

- The sword may have been borrowed from a Japanese antique and artifact importer in Boston or Salem.

- The samurai connection must be taken in cum grana salis as the samurai had been disestablished as a social classs, and individually and collectively referred to as shizoku (lit., “samurai group”), so something of the historical position and association were carried forward.

- “Hydesaburo Ohashi.” Cambridge Chronicle, February 28, 1903, p. 12.

© 2025 Aaron Cohen