Basil’s Return to Canada

Perhaps because he was several years older than the girls, Basil struggled the most trying to adjust to life in Japan. The sisters often noticed him reading English books by himself and believe that he was having an especially difficult time fitting into village society. They feel this was exacerbated by the severe treatment he received from both his father and his grandmother as the oldest child. Apparently both of his parents eventually realized he was not fitting in well and decided to send him to live with relatives in Canada. Megumi recalls:

Japan seemed to Basil totally different from Canada. The pressure on him was severe. We (his sisters) were still really small...but Basil was 7 years older than me so I’m sure it was much harder on him. There was no one to protect us, and mother had left... Mother and father were both absent, so Basil used to wander around aimlessly among the adults. He could understand when someone was angry at him, but not when he was being praised. At that time Father was very strict toward Basil. I remember him being angry... Basil had nowhere to go.

His maternal grandmother and aunts, who were living in Vernon (a town in the interior of British Columbia), sponsored his return to Canada. He recalls his father saying he thought it would be a good idea for him to return to Canada before he forgot English and became too entrenched in Japan.

Hence, in 1949, at the age of 12, after three years of living with his father and younger sisters in Shimosato, Basil returned to Canada. At that time Megumi and Emiko were five and four years old respectively. Basil stayed with his aunts and grandmother in Vernon from 1949 and moved with them to Vancouver in 1954. Not long after, his parents divorced. Because this information was kept from him by his mother, aunts, and grandmother, he did not learn about it until several years after the fact. He eventually graduated from university, spent several years as a high school teacher, and then had a long and successful career in the fish packing industry.

Following his return to Canada, Basil never saw his father or had direct contact with him again. However, during his time in Vernon, he met his father’s old friend, James Murakami, who had set up a new photography studio there. Basil occasionally visited with Murakami who was in contact with his father and gave Basil news about how he was doing. His grandmother and aunts maintained correspondence with his mother, and Basil exchanged a few letters with her at the beginning, but he would not see her again until she visited him in Canada in the mid 1970s. Likewise, he would not meet his sisters again until almost 45 years later in 1993.

Over the years he heard less and less about how his family members in Japan were faring. The sisters recall that both parents kept in touch with their relatives in Canada, and it was through that correspondence that they would get occasional news about how Basil was doing in Canada. Megumi recalls:

We did not have contact with Basil directly. We missed him, but there was also our parents’ divorce, and perhaps that all the more widened the distance between us... We heard from mother what kinds of work Basil was doing—that he got married, that he became a teacher, that he quit that job, that he moved and got a new job— we heard those things from Mother.

Life in Kyoto

Shortly after Basil returned to Canada, John and his two daughters moved to Kyoto to live with May close to the American base located near what is now Shimazu Seisakujo, and the family started a new phase of their lives together.

Despite having lived in Japan from their earliest childhood, Megumi and Emiko had a strong sense of being different from other children in school and feeling like they belonged to “a strange family.” Megumi recalls, “[We were different] in lots of ways. Somehow we felt so. We felt it keenly. As we gradually grew up, we still felt unusual and strange. Thinking about it now, perhaps we should not have felt that way.”

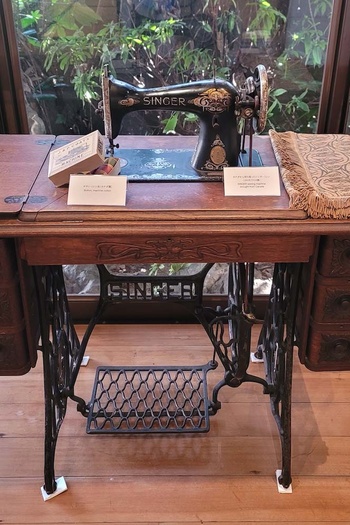

This feeling of being different was partly due to some of the ‘foreign’ items they had brought from Canada and were using in Japan. For instance, although they were sleeping on futons, they were using large feather quilts they had brought from Canada to stay warm. They recall feathers being everywhere when these quilts frayed and developed holes. They also recall their mother using a Singer sewing machine they had brought from Canada.

In addition, they received some coats with fur collars from relatives in Canada. When the children around them saw them wearing these coats, they teased them and called them Americans. Likewise, they were similarly teased because their mother May had their hair permed for a school entrance ceremony. They also noticed that May herself also stood out as different from the Japanese women around her. Specifically, they recall feeling ‘foreign’ at large school activities such as sports events due to their own appearance and their mother’s conspicuous appearance. Megumi says:

We were said to look like foreigners when we went to school sports competitions. At the competitions, all the parents would come to see their kids. At those events Mother kind of stood out, perhaps because of how she dressed. Maybe it also had something to do with our clothing. Or [we looked different] because we had been in the internment camps, I wonder. We were told that we had the air of foreigners.

She also relates a particularly amusing anecdote about how the English words spoken by their parents at home affected them in school.

When we were in school, there was a katakana spelling test [about English words in Japanese], and I spelled the word ‘cup’ in katakana closer to its English pronunciation (カップ = kuppu) rather than how it is pronounced and spelled in Japanese (コップ = koppu), so was marked wrong. Mother complained that カップ (kuppu) is the correct answer, because in our home we pronounced it that way. There were other similar situations.

Another language-related memory is of their feeling embarrassed because their parents would speak English to some friends when they would go as a family to the local sento (public bath) in Kyoto. Megumi explains:

At that time there was a sento nearby. We didn’t have a bath in our house. [Our parents] used to speak English with a woman named Miyauchi san when they were at the sento. I had the feeling they were friends with Miyauchi san, and I wondered if they had been in the camp together although I didn’t hear that they had been friends in Canada. They would suddenly start speaking in English. For us children it was embarrassing. Thinking back on it now, I feel sorry for us children at that time. Mother also spoke English in her sleep.

Sadly, their being different and conspicuous invited envy and discrimination from people around them. For instance, the western clothing worn by the family caused envious reactions from others:

We had aunts in Canada, and they sent us western-style clothing. ...We also received old leather shoes from them, although in those days, leather shoes were not worn in Japan. Geta (traditional Japanese wooden sandals) were still worn in schools in those days and kids ran barefoot in the playground. We had leather shoes sent to us from our aunts in Canada, and when we wore them we were bullied... Although we were poor at that time, when we wore coats with fur attached to school, people would say, “Americans!” When we experienced such things, we came to realize that we were somehow really different from other people.

© 2021 Stan Kirk