Before World War II, my grandparents, my father, and his siblings were sharecroppers. I have a few stories of what that was like from my father and his siblings, but there is more I would like to know about what they raised, where and how they lived. And it’s harder to find accounts of rural Nikkei, Nikkei farmers, and their stories in official historic records.

The Kansha History Project addresses this type of gap in an exciting community-sourced, community-powered effort. Founded and directed by Yonsei community leader Amanda Mei Kim in California (as well as an advisory board), the project aims to transcribe some 7,000 land transfer records from the wartime Farm Security Administration.

Before the war, many Nikkei farmers had cultivated land successfully, contributing to the West Coast agricultural economy and raising many crops successfully—growing as much as 40 percent of all vegetables and nearly 100 percent of all tomatoes in California. As the Densho Catalyst explains, because of racist land laws, the Nikkei farmers were unable to own land, but some were able to rent land in the names of their American-born children.

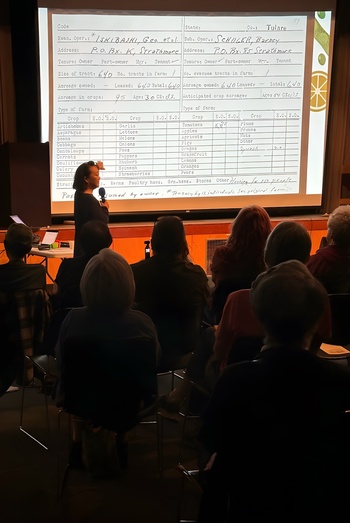

Due to wartime incarceration, thousands of Nikkei farmers lost the land that they had cultivated and rented (in some cases, for decades). The land transfer records are records of the crops they raised, the structures of land, and housing, all documented by federal field agents. They had been digitized—however, the compiled records were difficult to search even in a digital format, since they were unmarked files, too large to open, and not indexed.

Indeed, one of the most remarkable aspects of the project is its community sharing events: giving the data back to the community, rather than immediately trying to publish it somewhere or using a format less accessible for community members. Online attendees at a Kansha History Project event I attended in November 2024 included community members, members of sponsoring organizations, descendants, and volunteers for the project. Descendants shared their family stories and volunteers (several of them also descendants) shared how meaningful it was to see their family history in this light. The project event allows community members to process the impact of seeing these family stories, often for the first time or in a new light.

I had a chance to ask Kim about the project over e-mail in December 2024.

Tamiko Nimura: You’ve written beautifully about your family history (and its roots in farming) here at Discover Nikkei and at The Common. Can you talk a bit about the origin of the Kansha History Project? Did the idea come to you all at once, or did it grow and develop over time?

Amanda Mei Kim (AMK): Growing up, I heard people talk about Nikkei farmers every day. I lived and worked on a truck farm in Ventura County, in the community where my grandparents ended up after they were released from Tule Lake. My Korean American father was a produce broker, so he had a huge Rolodex of Nikkei farmers and a ring-bound address book that he kept in his truck. We visited a lot of Nikkei farms and gardens, and I saw how much people loved their plants. I knew that there was something unique about that relationship to the land.

A few years ago, I noticed that our farming history hadn’t been well documented, so I started interviewing farmers and researching farming practices and especially my family’s dry-farming history. Eventually, I found these records. As soon as I saw them, I knew they would be important to a lot of people. I spent about a year trying to find an organization that would take this project, but they couldn’t imagine recruiting, training, and supervising hundreds of volunteers. At that point, I think my rural upbringing kicked in because I got the idea that we could do it ourselves, as a community project. I felt pretty sure that people would pitch in out of love and honor for their ancestors, and they really have.

TN: Can you give DN readers a bird’s eye sense of the numbers now for the project? How many family records have been transcribed, how many volunteers, how many community events? How many areas or regions has the project reached, and which ones?

AMK: We have transcribed about 2,000, proofed about 2,000 and have about 1,500 to go. We’ve had events in Contra Costa (75 people) and Sacramento (230 people) counties, as well as the Poston Pilgrimage and a couple of online events.

180 people have attended orientations to hear about the project and we have had 100 volunteers participate in our sprints. We would like to have events in the Central Valley, Central Coast and Los Angeles next.

TN: What are your hopes and goals moving forward with the project—short-term and long term? What’s next for the project?

AMK: Our short-term goal is to complete this dataset by June [2025]. We are already exploring adding more sets of records, doing some interpretation and offering more community events. I would like to share this information at as many Nikkei nursing and retirement homes as possible. It’s been amazing to see the community reaction. People have said that this is the first time that their family’s farming contributions have ever been acknowledged. According to the evaluations, attendees feel inspired, enlightened, empowered and connected.

I don’t know what the long-term outcome of this project will be, but I hope that this information will enrich how people see their family histories and historical events. This project also shows that Japanese Americans are remarkable farmers with an extraordinary impact. It gives volunteers a deep experience of empathy and community power. It shows institutions that records like this are extremely important and should be made more easily available.

© 2025 Tamiko Nimura