In 2010, I was privileged to provide a peer evaluation of the late Lane Hirabayashi to support a step promotion for him as a full professor in the Asian American Studies Department at the University of California, Los Angeles. In my assessment, I emphasized his pervasive concern for “community,” both as a scholar and a teacher.

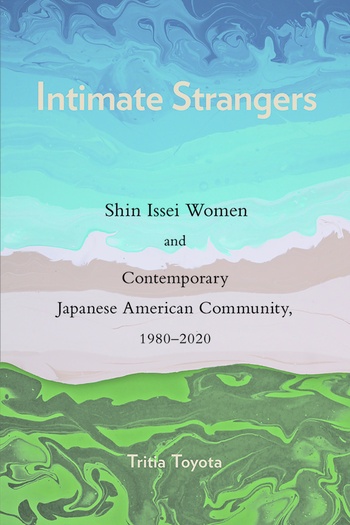

So, I was not surprised to read in the acknowledgments section of Tritia Toyota’s ethnographic masterpiece, Intimate Strangers: Shin Issei Women and Contemporary Japanese American Community, 1980-2020, here under scrutiny that she regarded Lane, an anthropological colleague at UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center, as an academic mentor who stressed to her how anthropological research could enhance community change.

Nor was I startled by her disclosure in the same context that for years the two of them had held many “lively discussions” over the topic of the present book under scrutiny. This was because in 2016 I had been tasked with reviewing for the Nichi Bei Weekly a new publication edited by Lane, “Conjecturing Communities: Ebbs and Flows of Japanese America,” in which he featured contemporary scholarship on six groups, including Shin-Issei, “that may, or may very well not, become part of the larger Japanese American community in the twenty-first century.”

In the meticulous introduction to her ethnography (i.e., a written report that the ethnographer produces following intensive fieldwork in the culture and everyday life of the people who are the subject of her/his study), Toyota informs readers of some critical information bearing on her research. First, that her focus was on Shin (i.e. new) Issei (migrants from Japan to the U.S.), who were young (20-somethings) and mostly unmarried middle-and-lower class urbanized women of limited education and exclusively Japanese-speaking facility, who beginning in the 1980s, left their homes and lives in Japan because of a combination of the breakdown of the Japanese economy and, owing in no small part to male chauvinism, inability to find employment that paid survivable wages.

Second, that her fieldwork began in 2008 and, for the most part, ended in 2017, included interviews, obtained through a “modified snowball technique,” with more than 60 foreign-born Japanese and native-born Americans of Japanese ancestry in the westside of Los Angeles, most especially the traditional Japanese American area of Sawtelle, but extending to interactions with informants in the South Bay and Little Tokyo regions of the so-called City of the Angels.

Third, that her in-depth fieldwork interviews (conducted primarily in English), were treated with proper consideration to concerns of confidentiality, particularly since the majority of the Shin-Issei women lived within the U.S. (initially as bar hostesses and waitresses and later as other types of marginal workers) of great precariousness due to their undocumented status.

As for the text of the volume, it consists of six substantial (well-composed and richly documented) chapters, plus an epilogue. Chapter 1, “Wilting Office Flowers,” explores the severe restrictions faced by Shin-Issei in an overhauled economic order in Japan that both disparaged them as sponges and robbed them of career prospects.

Chapter 2, “Leaving Home,”examines how the Shin-Issei facilitated their migration to the U.S. by capitalizing upon “larger global and economic structures.”

Chapter 3, “Precarious Life under the Radar,”clarifies how Shin-Issei have persevered as migrant workers without legal certification and done so in the face of possible apprehension and deportation.

Chapter 4, “Surviving around the Neighborhoods,” depicts how Shin-Issei women capitalized upon the existence of an international presence of their native Japan in Los Angeles to facilitate their inclusion.

Chapter 5, “Racial Talk,” explores how Shin-Issei and Nikkei perceive one another as unalike and separate groups, replete with racial ramifications.

Chapter 6, “Shin Issei and Nikkei Searching for Community,” the most consequential section of the book in terms of the future of the Japanese American community, posits, in the judicious words of Toyota, that “establishing intergroup social solidarity is a task where outcomes may also be accepted as constitutive of coalition building in community work” (p. 173).

As for the epilogue, it provides a forum for Toyota to redeem a generic promissory note she floated in her introduction, which is to not only uncover “tensions wrought by new migration in extant American communities . . . (but also, especially with the emergence in the twenty-first century of a Shin-Nisei population) to go “a step further to investigate possibilities of common purpose or integrated action on social issues that are inclusive of both Nikkei and Shin-Issei under a larger, encompassing umbrella of belonging”(p. 5).

Intimate Strangers is a landmark book. Hopefully, it is a prelude to subsequent studies that will take up the experience of other new populations within the ever-changing Japanese American community.

INTIMATE STRANGERS: SHIN ISSEI WOMEN AND CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE AMERICAN COMMUNITY, 1980 - 2020

By TritiaToyota

(Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2023, 226 pp., $32.95 paperback)

* This article was originally published in Nichi Bei News on July 18, 2024.

© 2024 Art Hansen, Nichi Bei News