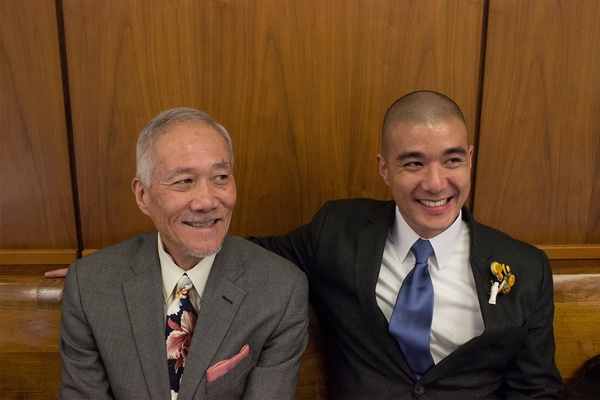

Kenyon Mayeda is the new Chief Impact Officer for the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), a position which among other things, involves the daily running of the museum. He remembers early trips to the Manzanar concentration camp with his father, Mark Mayeda. It was before there was a museum, with some areas covered with broken dishes and trash. While returning to Manzanar as a child, Kenyon’s father would find empty shotgun shells and ammunition cases leftover from target practice. Although his father was only an infant when he left Manzanar, he would say, “I was born here. I have a feeling about this place, this location.”

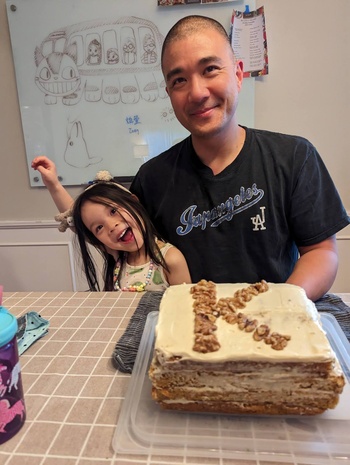

His father did not openly share family stories about Manzanar, but Kenyon was able to piece together information by asking many questions. Kenyon and his wife are the parents of two daughters, ages 2 years and 5 years old. Being a father has made him realize how challenging it must have been to raise a family in that desolate, hostile environment. He plans to take his daughters to Manzanar when they are older.

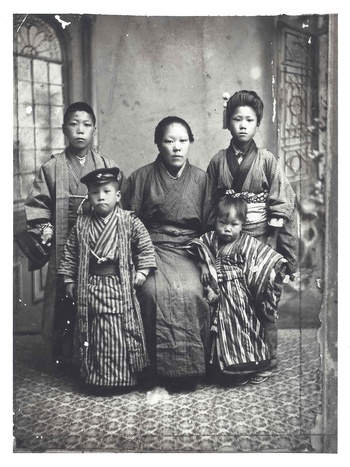

Kenyon is of mixed Asian heritage, with a Japanese American father, a Chinese American mother, and two older sisters. His Japanese grandfather, Sangoro Mayeda, immigrated to the US in 1915. His Japanese grandmother, Emily Mayeda, was born and raised in Oakland. His grandparents were forcibly relocated from the Bay Area to Manzanar. At the time, Sangoro was working at a farm in Florin, California. Before they left Manzanar, the minister asked Sangoro to return yearly to perform services at the cemetery. It was a responsibility he did each year until his passing.

After Manzanar, the Mayedas moved to Los Angeles with their two children, a young daughter and infant son Mark. They lived wherever they could afford, sometimes in people’s garages. The family grew to have five children, two daughters and three sons. Sangoro worked as a gardener for the artists Charles and Ray Eames at their Venice studio. Charles and his wife Ray were married artists who were pioneers in the design of modern buildings and furniture. Their Eames chairs are iconic examples of 20th century American modernism. Emily worked as their housekeeper and later as their fulltime cook. The Mayeda family received an Eames chair after the passing of Ray Eames, a gift to Sangoro and Emily.

They eventually saved enough to buy a house in a working class neighborhood in Venice. Workers from the nearby seaside resort and hotel lived there. It was predominately an African American neighborhood, with few Japanese Americans. The Mayedas were active in the Gardena Buddhist Temple. Sangoro passed away before Kenyon was born, but he knows about him through his father’s stories. He remembers Emily from his early childhood, though she developed Alzheimers.

He said, “As far as I have come from that place, I still see how it is that any privilege that I’ve experienced in my life was really based on the commitments that they made, their work ethic, their dedication to the community to ensure not only that Manzanar was a place that was remembered, but to provide for their family. It enabled my father to give me the life that I live. I see that connection despite the fact that my grandfather passed before I was born.”

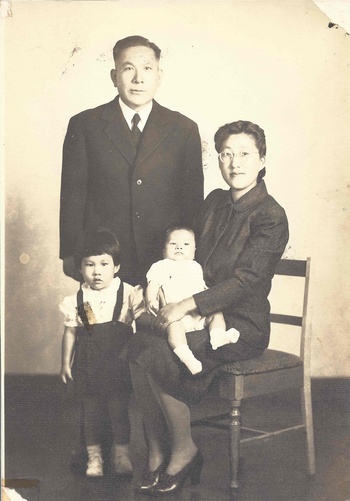

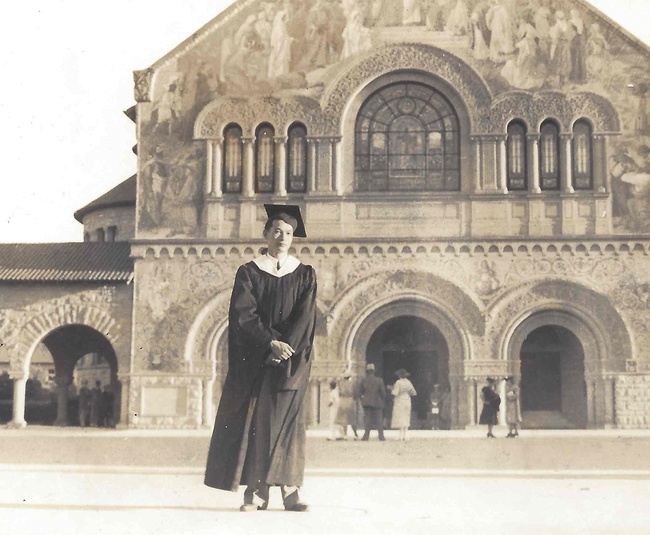

Kenyon’s Chinese grandfather, George T.M. Ching, was born in Berkeley in 1914. George’s father was a political science student in Berkeley. He returned to China, where George grew up. George returned as a young adult to attend Stanford University from 1937-1939, earning a master’s degree in economics with an emphasis in banking. He married Tsui Lin Ching and was a banker in Hong Kong after WWII. In 1951, the family fled the Communists and moved to Los Angeles. At first, Ching worked three jobs to support his family.

He later became one of the founders of Cathay Bank, which opened in Los Angeles in 1962, and served as the first President and CEO. It was the first bank owned and operated by Chinese Americans in Southern California. Deborah Ching, George’s daughter, said her father realized that many first-generation Chinese immigrants were being denied loans at major banks. She said, “and that affected how to start a business, how to start a home, how to buy a car even or send your children to school. And that’s what he wanted to help with.”

Kenyon’s mother, Deborah Ching, was the youngest of three daughters. He grew up knowing his Chinese grandparents, often spending time in the Los Angeles Chinatown. His mother was Executive Director of the Chinatown Service Center. Kenyon also spent a lot of time in Koreatown, where his father had a leadership role at the Koreatown Youth and Community Center (KYCC). His parents placed a lot of emphasis on community and service to others. Kenyon joined the KYCC student group and became president of the Korean Coalition of Students in California, though he was the only non-Korean. It allowed him to find his place in other Asian communities.

Kenyon also has fond memories of mochitsuki, obons, fundraisers, and events at the Venice Buddhist Temple where his family was active. He remembers the delicious food, the kids running around, connecting with friends, and the familiarity of being with uncles, aunties, and family.

As a mixed heritage household, his parents had to compromise about food. “When you live in a multicultural household, at least mine, you have to make some decisions because the Chinese side eats long grain rice and my dad grew up eating short grain rice,” said Kenyon. His parents decided to eat short grain rice and cooked both Japanese and Chinese food. His mom was a vegetarian or vegan so they ate lots of vegetables. In addition, there was a wide variety of Los Angeles food to select from including American, Mexican, Korean, and other ethnic dishes.

During middle school he went to Kaizuka, Japan on a sister city exchange. He felt “culture shock” as a Japanese American staying with a traditional Japanese family. He was only able to communicate in English with one of the daughters. He graduated from Culver City High. He attended the University of San Francisco from 2003-2006, majoring in business administration.

In 2004, he was a summer intern at JANM where he was able to meet leaders from other Japantowns. Executive Director Jon Osaki introduced him to the Japanese Community Youth Council (JCYC). The JCYC is a San Francisco nonprofit that serves children, youth, and families. Kenyon worked there as a preschool teacher, summer camp director, and in their community programs.

Kenyon is a 2012 alumni of the Emerging Leaders Program (ELP), part of the U.S.-Japan Council. He is currently the U.S.-Japan Council Southern California Regional Chair. While working as a Regional Operation Officer for the Cathay Bank in Seattle, he networked with the leaders of immigrant communities and built relationships to fund neighborhood organizations.

He views his work with the multicultural and community-driven ad agency TDW+Co, to have been “a period of time which was very meaningful.” This included the 2020 Census outreach to the Asian American community. In six different Asian language ads, cute little Asian girls persuade their fathers to fill out the U.S. Census forms. TDW+Co also supported a Proctor & Gamble campaign about the importance of names, which emphasized the importance of belonging and addressed issues such as anti-Asian bias and violence. It included celebrities such as Michelle Yeoh and Daniel Dae Kim.

His parents were “thrilled” when he got the museum job. Kenyon said, “They are not only great cheerleaders, but they are also great advisors in the fields of nonprofits.” He feels he has made a full circle in returning to a nonprofit after being in the corporate world.Kenyon said, “The museum is already in a transformative phase with the redoing of the core exhibit, with the renovation of the museum itself. It is really an investment to set this institution up for future generations.” He hopes it will be meaningful for his own kids when they grow up. “How does the collection of the museum evolve to reflect the increasingly multicultural, multiracial Japanese American community?”

He said, “I’m thinking about the museum as it exists after I’m gone from here. I hope that my children will still come and feel connected to this place.” His parents added the names of Kenyon and his sister to the Children’s Courtyard when the museum opened. Now his own kids’ names are there, too.

© 2024 Edna Horiuchi